|

OLD INNS |

| << CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS |

| OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS >> |

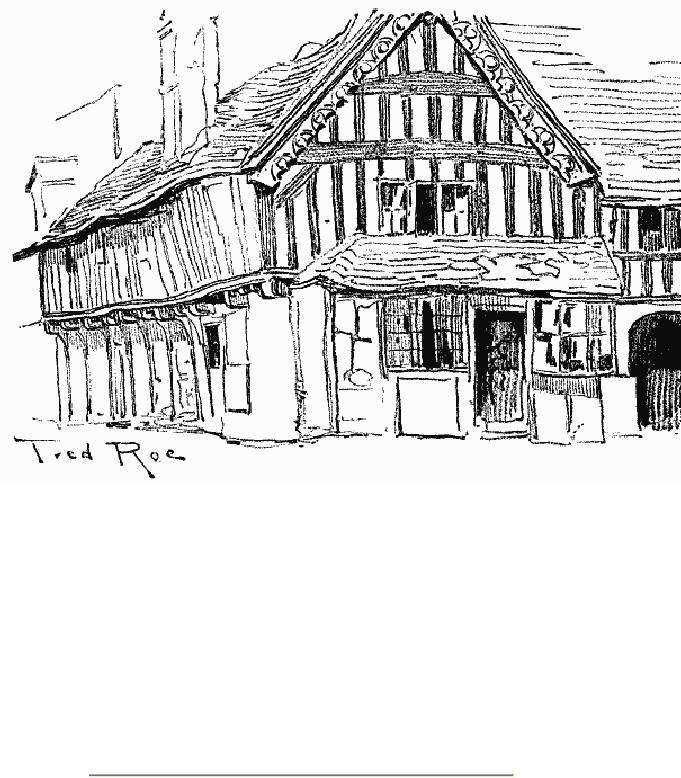

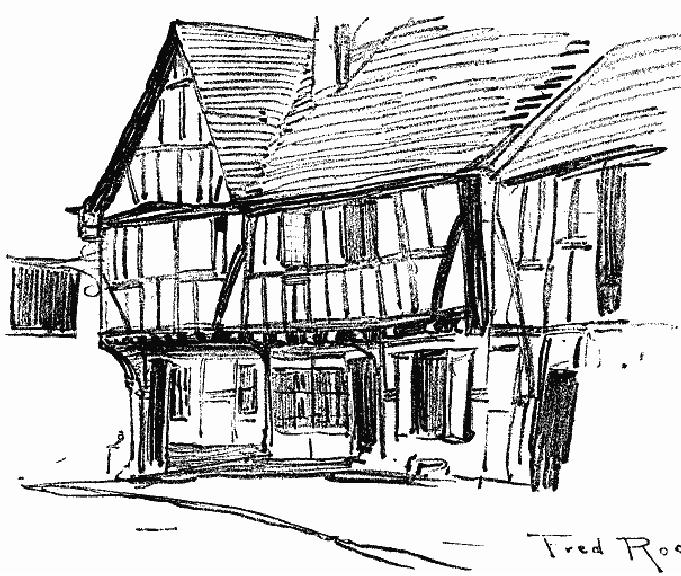

Half-timber

House at Alcester

There is

much in the neighbourhood of

Evesham which is worthy of

note, many old

-fashioned

villages and country towns,

manor-houses, churches, and inns

which are

refreshing

to the eyes of those who

have seen so much

destruction, so much of

the

England

that is vanishing. The old

abbey tithe-barn at Littleton of the

fourteenth

century,

Wickhamford Manor, the home

of Penelope Washington, whose

tomb is in

the

adjoining church, the

picturesque village of Cropthorne,

Winchcombe and its

houses,

Sudeley Castle, the timbered

houses at Norton and Harvington,

Broadway

and

Campden, abounding with beautiful houses,

and the old town of

Alcester, of

which

some views are given--all

these contain many objects

of antiquarian and

artistic

interest, and can easily be

reached from Evesham. In

that old town we

have

seen

much to interest, and the

historian will delight to fight

over again the battle

of

Evesham

and study the records of the

siege of the town in the

Civil War.

CHAPTER

X

OLD

INNS

The

trend of popular legislation is in

the direction of the

diminishing of the

number

of

licensed premises and the

destruction of inns. Very soon, we

may suppose, the

"Black

Boy" and the "Red

Lion" and hosts of other old signs will

have vanished,

and

there will be a very large

number of famous inns which

have "retired from

business."

Already their number is

considerable. In many towns

through which in

olden

days the stage-coaches passed

inns were almost as

plentiful as blackberries;

they

were needed then for

the numerous passengers who

journeyed along the

great

roads

in the coaches; they are

not needed now when people

rush past the places

in

express

trains. Hence the order

has gone forth that these

superfluous houses

shall

cease

to be licensed premises and must

submit to the removal of

their signs. Others

have

been so remodelled in order to

provide modern comforts and

conveniences

that

scarce a trace of their old-fashioned

appearance can be found.

Modern

temperance

legislators imagine that if

they can only reduce the

number of inns they

will

reduce drunkenness and make the English

people a sober nation. This is

not the

place

to discuss whether the

destruction of inns tends to promote

temperance. We

may,

perhaps, be permitted to doubt the

truth of the legend, oft

repeated on

temperance

platforms, of the working

man, returning homewards

from his toil,

struggling

past nineteen inns and

succumbing to the syren

charms of the

twentieth.

We

may fear lest the

gathering together of large

numbers of men in a few

public-

houses

may not increase rather

than diminish their thirst

and the love of good

fellowship

which in some mysterious way

is stimulated by the imbibing of

many

pots

of beer. We may, perhaps, feel

some misgiving with regard to

the temperate

habits

of the people, if instead of well-conducted

hostels, duly inspected by

the

police,

the landlords of which are

liable to prosecution for

improper conduct, we

see

arising a host of ungoverned

clubs, wherein no control is exercised

over the

manners

of the members and adequate

supervision impossible. We cannot

refuse to

listen

to the opinion of certain

royal commissioners who,

after much sifting of

evidence,

came to the conclusion that

as far as the suppression of

public-houses had

gone,

their diminution had not

lessened the convictions for

drunkenness.

But

all this is beside our

subject. We have only to

record another feature

of

vanishing

England, the gradual

disappearance of many of its

ancient and historic

inns,

and to describe some of the

fortunate survivors. Many of

them are very

old,

and

cannot long contend against

the fiery eloquence of the

young temperance

orator,

the newly fledged justice of

the peace, or the budding

member of Parliament

who

tries to win votes by

pulling things down.

We

have, however, still some of

these old hostelries left;

medieval pilgrim inns

redolent

of the memories of the not

very pious companies of men and

women who

wended

their way to visit the

shrines of St. Thomas of

Canterbury or Our Lady

at

Walsingham;

historic inns wherein some

of the great events in the

annals of

England

have occurred; inns

associated with old romances or

frequented by

notorious

highwaymen, or that recall

the adventures of Mr. Pickwick

and other

heroes

and villains of Dickensian tales. It is

well that we should try to

depict some

of

these before they altogether

vanish.

There

was nothing vulgar or disgraceful

about an inn a century ago.

From

Elizabethan

times to the early part of

the nineteenth century they

were frequented

by

most of the leading spirits

of each generation. Archbishop

Leighton, who died in

1684,

often used to say to Bishop

Burnet that "if he were to

choose a place to die in

it

should be an inn; it looked

like a pilgrim's going home,

to whom this world

was

all

as an Inn, and who was weary of

the noise and confusion of it."

His desire was

fulfilled.

He died at the old Bell Inn in

Warwick Lane, London, an old

galleried

hostel

which was not demolished

until 1865. Dr. Johnson,

when delighting in

the

comfort

of the Shakespeare's Head Inn,

between Worcester and

Lichfield,

exclaimed:

"No, sir, there is nothing

which has yet been

contrived by man, by

which

so much happiness is provided as by a

good tavern or inn." This

oft-quoted

saying

the learned Doctor uttered

at the Chapel House Inn,

near King's Norton;

its

glory

has departed; it is now a simple

country-house by the roadside.

Shakespeare,

who

doubtless had many opportunities of

testing the comforts of the

famous inns at

Southwark,

makes Falstaff say: "Shall I

not take mine ease at mine

inn?"; and

Shenstone

wrote the well-known rhymes

on a window of the old Red

Lion at

Henley-on-Thames:--

Whoe'er

has travelled life's dull

road,

Where'er

his stages may have

been,

May

sigh to think he still has

found

The

warmest welcome at an

inn.

Fynes

Morrison tells of the

comforts of English inns

even as early as the

beginning

of

the seventeenth century. In 1617 he

wrote:--

"The

world affords not such

inns as England hath, for as

soon as a

passenger

comes the servants run to

him; one takes his horse and

walks

him

till he be cold, then rubs

him and gives him meat;

but let the

master

look to this point. Another

gives the traveller his

private

chamber

and kindles his fire, the

third pulls off his boots

and makes

them

clean; then the host or

hostess visits him--if he will

eat with the

host--or

at a common table it will be 4d. and

6d. If a gentleman

has

his

own chamber, his ways

are consulted, and he has

music, too, if he

likes."

The

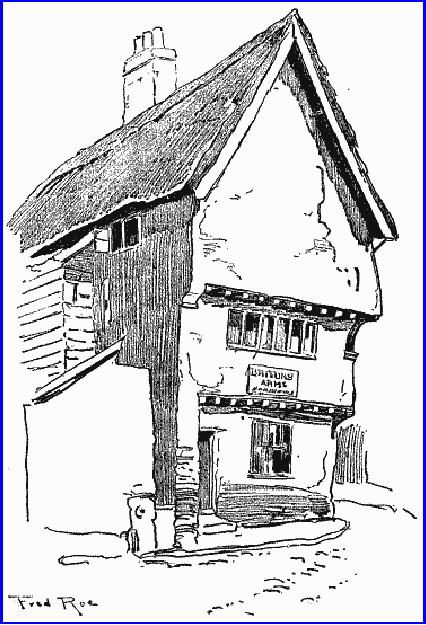

Wheelwrights' Arms,

Warwick

The

literature of England abounds in references to

these ancient inns. If

Dr.

Johnson,

Addison, and Goldsmith were

alive now, we should find

them chatting

together

at the Authors' Club, or the

Savage, or the Athenĉum.

There were no

literary

clubs in their days, and

the public parlours of the

Cock Tavern or the

"Cheshire

Cheese" were their clubs,

wherein they were quite as

happy, if not quite

so

luxuriously housed, as if they had been

members of a modern social

institution.

Who

has not sung in praise of

inns? Longfellow, in his

Hyperion,

makes Flemming

say:

"He who has not

been at a tavern knows not

what a paradise it is. O

holy

tavern!

O miraculous tavern! Holy,

because no carking cares are

there, nor

weariness,

nor pain; and miraculous,

because of the spits which of

themselves

turned

round and round." They

appealed strongly to Washington

Irving, who, when

recording

his visit to the shrine of

Shakespeare, says: "To a homeless man,

who has

no

spot on this wide world

which he can truly call his

own, there is a

momentary

feeling

of something like independence and

territorial consequence, when after

a

weary

day's travel he kicks off

his boots, thrusts his feet

into slippers, and

stretches

himself

before an inn fire. Let

the world without go as it

may; let kingdoms rise

or

fall,

so long as he has the

wherewithal to pay his bill,

he is, for the time

being, the

very

monarch of all he surveys....

'Shall I not take mine ease

in mine inn?' thought

I,

as I gave the fire a stir,

lolled back in my elbow chair,

and cast a complacent

look

about

the little parlour of the

Red Horse at Stratford-on-Avon."

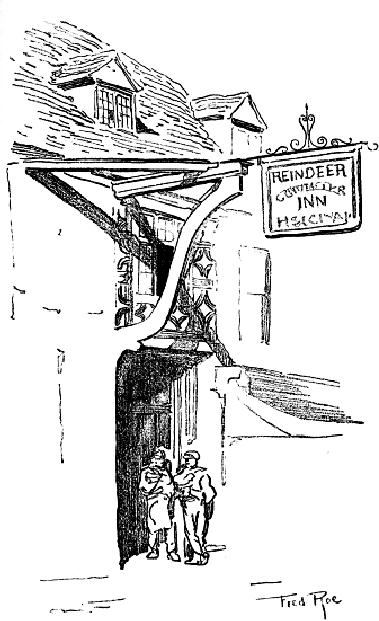

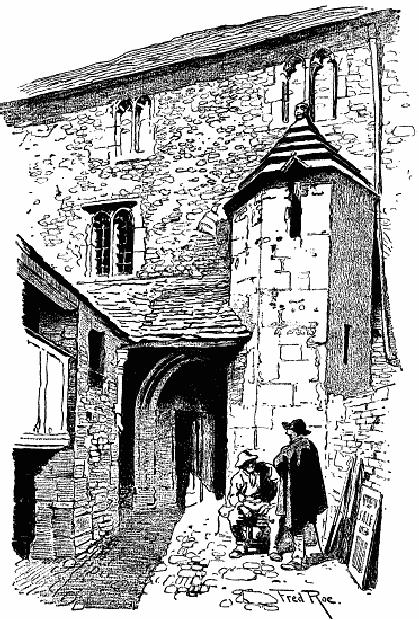

Entrance

to the Reindeer Inn,

Banbury

And

again, on Christmas Eve Irving

tells of his joyous long

day's ride in a coach,

and

how he at length arrived at a

village where he had determined to

stay the night.

As

he drove into the great

gateway of the inn (some of

them were mighty

narrow

and

required much skill on the

part of the Jehu) he saw on one

side the light of a

rousing

kitchen fire beaming through

a window. He "entered and admired,

for the

hundredth

time, that picture of

convenience, neatness, and broad

honest

enjoyment--the

kitchen of an English inn." It was of

spacious dimensions,

hung

round

with copper and tin vessels

highly polished, and decorated here and

there

with

Christmas green. Hams, tongues,

and flitches of bacon were

suspended from

the

ceiling; a smoke-jack made

its ceaseless clanking

beside the fire-place, and

a

clock

ticked in one corner. A well-scoured deal

table extended along one

side of the

kitchen,

with a cold round of beef and

other hearty viands upon

it, over which

two

foaming

tankards of ale seemed mounting

guard. Travellers of inferior

order were

preparing

to attack this stout repast,

while others sat smoking

and gossiping over

their

ale on two high-backed oaken settles

beside the fire. Trim

housemaids were

hurrying

backwards and forwards under

the directions of a fresh

bustling landlady;

but

still seizing an occasional

moment to exchange a flippant

word, and have a

rallying

laugh with the group

round the fire.

Such

is the cheering picture of an

old-fashioned inn in days of yore. No

wonder that

the

writers should have thus

lauded these inns! Imagine

yourself on the box-seat

of

an

old coach travelling somewhat

slowly through the night. It

is cold and wet, and

your

fingers are frozen, and the

rain drives pitilessly in

your face; and then,

when

you

are nearly dead with

misery, the coach stops at a

well-known inn. A

smiling

host

and buxom hostess greets

you; blazing fires thaw

you back to life, and good

cheer

awaits your appetite. No wonder people

loved an inn and wished to take

their

ease

therein after the dangers

and hardships of the day.

Lord Beaconsfield, in

his

novel

Tancred,

vividly describes the busy

scene at a country hostelry in

the busy

coaching

days. The host, who is

always "smiling," conveys

the pleasing

intelligence

to the passengers: "'The coach

stops here half an hour,

gentlemen:

dinner

quite ready.' 'Tis a

delightful sound. And what a

dinner! What a profusion

of

substantial

delicacies! What mighty and

iris-tinted rounds of beef!

What vast and

marble-veined

ribs! What gelatinous veal

pies! What colossal hams! These

are

evidently

prize cheeses! And how

invigorating is the perfume of those

various and

variegated

pickles. Then the bustle

emulating the plenty; the

ringing of bells, the

clash

of thoroughfare, the summoning of

ubiquitous waiters, and the

all-pervading

feeling

of omnipotence from the guests,

who order what they

please to the

landlord,

who

can produce and execute everything

they can desire. 'Tis a

wondrous sight!"

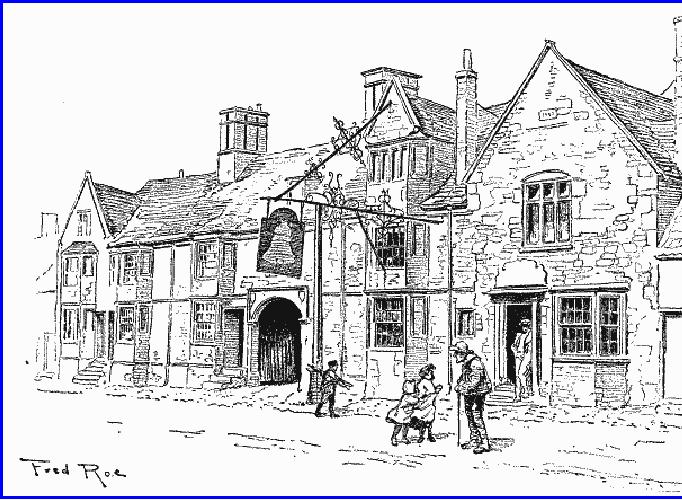

The

Shoulder of Mutton Inn,

King's Lynn

And

then how picturesque these

old inns are, with

their swinging signs, the

pump

and

horse-trough before the

door, a towering elm or

poplar overshadowing the

inn,

and

round it and on each side of

the entrance are seats,

with rustics sitting on

them.

The

old house has picturesque

gables and a tiled roof

mellowed by age, with

moss

and

lichen growing on it, and

the windows are latticed. A

porch protects the

door,

and

over it and up the walls are

growing old-fashioned climbing

rose trees.

Morland

loved to paint the exteriors

of inns quite as much as he

did to frequent

their

interiors, and has left us

many a wondrous drawing of

their beauties. The

interior

is no less picturesque, with

its open ingle-nook, its

high-backed settles, its

brick

floor, its pots and pans,

its pewter and brass

utensils. Our artist has

drawn for

us

many beautiful examples of

old inns, which we shall

visit presently and try

to

learn

something of their old-world

charm. He has only just

been in time to

sketch

them,

as they are fast disappearing. It is

astonishing how many noted

inns in

London

and the suburbs have

vanished during the last

twenty or thirty

years.

Let

us glance at a few of the great

Southwark inns. The old

"Tabard," from which

Chaucer's

pilgrims started on their memorable

journey, was destroyed by a great

fire

in 1676, rebuilt in the old

fashion, and continued until

1875, when it had to

make

way for a modern "old

Tabard" and some hop

merchant's offices. This

and

many

other inns had galleries

running round the yard, or

at one end of it, and this

yard

was a busy place, frequented not

only by travellers in coach or saddle,

but by

poor

players and mountebanks, who

set up their stage for

the entertainment of

spectators

who hung over the

galleries or from their

rooms watched the

performance.

The model of an inn-yard was

the first germ of theatrical

architecture.

The

"White Hart" in Southwark

retained its galleries on

the north and east side

of

its

yard until 1889, though a

modern tavern replaced the

south and main portion

of

the

building in 1865-6. This was

a noted inn, bearing as its

sign a badge of

Richard

II,

derived from his mother

Joan of Kent. Jack Cade

stayed there while he was

trying

to capture London, and another

"immortal" flits across the

stage, Master Sam

Weller,

of Pickwick

fame.

A galleried inn still

remains at Southwark, a great

coaching

and carriers' hostel, the

"George." It is but a fragment of

its former

greatness,

and the present building was erected soon

after the fire in 1676, and

still

retains

its picturesqueness.

The

glory has passed from

most of these London inns.

Formerly their yards

resounded

with the strains of the

merry post-horn, and carriers' carts

were as

plentiful

as omnibuses now are. In the

fine yard of the "Saracen's

Head," Aldgate,

you

can picture the busy scene,

though the building has

ceased to be an inn, and

if

you

wished to travel to Norwich

there you would have

found your coach ready

for

you.

The old "Bell Savage," which

derives its name from one

Savage who kept

the

"Bell

on the Hoop," and not from

any beautiful girl "La

Belle Sauvage," was a great

coaching

centre, and so were the

"Swan with two Necks,"

Lad Lane, the

"Spread

Eagle"

and "Cross Keys" in Gracechurch Street,

the "White Horse," Fetter

Lane,

and

the "Angel," behind St.

Clements. As we do not propose to

linger long in

London,

and prefer the country towns

and villages where relics of

old English life

survive,

we will hie to one of these noted

hostelries, book our seats

on a Phantom

coach,

and haste away from

the great city which has

dealt so mercilessly with

its

ancient

buildings. It is the last

few years which have wrought

the mischief. Many of

these

old inns lingered on till

the 'eighties. Since then

their destruction has

been

rapid,

and the huge caravanserais, the

"Cecil," the "Ritz," the

"Savoy," and the

"Metropole,"

have supplanted the old

Saracen's Heads, the Bulls,

the Bells, and the

Boars

that satisfied the needs of

our forefathers in a less

luxurious age.

Let

us travel first along the

old York road, or rather select

our route, going by

way

of

Ware, Tottenham, Edmonton, and

Waltham Cross, Hatfield and Stevenage,

or

through

Barnet, until we arrive at

the Wheat Sheaf Inn on Alconbury

Hill, past

Little

Stukeley, where the two

roads conjoin and "the

milestones are

numbered

agreeably

to that admeasurement," viz. to

that from Hicks' Hall

through Barnet, as

Patterson's

Roads plainly

informs us. Along this road

you will find several of

the

best

specimens of old coaching

inns in England. The famous

"George" at

Huntingdon,

the picturesque "Fox and

Hounds" at Ware, the grand

old inns at

Stilton

and Grantham are some of the

best inns on English roads,

and pleadingly

invite

a pleasant pilgrimage. We might follow in

the wake of Dick Turpin, if

his

ride

to York were not a myth. The

real incident on which the

story was founded

occurred

about the year 1676,

long before Turpin was born.

One Nicks robbed a

gentleman

on Gadshill at four o'clock in

the morning, crossed the

river with his bay

mare

as soon as he could get a ferry-boat at

Gravesend, and then by

Braintree,

Huntingdon,

and other places reached York

that evening, went to the

Bowling

Green,

pointedly asked the mayor

the time, proved an alibi,

and got off.

This

account

was published as a broadside

about the time of Turpin's

execution, but it

makes

no allusion to him whatever. It

required the romance of the

nineteenth

century

to change Nicks to Turpin and the

bay mare to Black Bess. But

revenir

à

nos

moutons, or rather

our inns. The old

"Fox and Hounds" at Ware is

beautiful

with

its swinging sign suspended

by graceful and elaborate ironwork and

its dormer

windows.

The "George" at Huntingdon

preserves its gallery in the

inn-yard, its

projecting

upper storey, its outdoor

settle, and much else

that is attractive.

Another

"George"

greets us at Stamford, an ancient

hostelry, where Charles I stayed

during

the

Civil War when he was

journeying from Newark to

Huntingdon.

And

then we come to Grantham, famous

for its old inns.

Foremost among them

is

the

"Angel," which dates back to

medieval times. It has a

fine stone front with

two

projecting

bays, an archway with

welcoming doors on either hand, and above

the

arch

is a beautiful little oriel

window, and carved heads and

gargoyles jut out

from

the

stonework. I think that this

charming front was remodelled in

Tudor times, and

judging

from the interior

plaster-work I am of opinion that

the bays were added

in

the

time of Henry VII, the Tudor

rose forming part of the

decoration. The arch

and

gateway

with the oriel are

the oldest parts of the

front, and on each side of

the arch

is

a sculptured head, one representing

Edward III and the other

his queen, Philippa

of

Hainault. The house belonged in

ancient times to the Knights

Templars, where

royal

and other distinguished

travellers were entertained.

King John is said to

have

held

his court here in 1213, and

the old inn witnessed

the passage of the body

of

Eleanor,

the beloved queen of Edward I, as it

was borne to its last

resting-place at

Westminster.

One of the seven Eleanor

crosses stood at Grantham on St.

Peter's

Hill,

but it shared the fate of

many other crosses and was

destroyed by the

troopers

of

Cromwell during the Civil

War. The first floor of

the "Angel" was occupied

by

one

long room, wherein royal

courts were held. It is now

divided into three

separate

rooms.

In this room Richard III

condemned to execution the

Duke of Buckingham,

and

probably here stayed Cromwell in the

early days of his military

career and

wrote

his letter concerning the

first action that made

him famous. We can

imagine

the

silent troopers assembling in

the market-place late in the

evening, and then

marching

out twelve companies strong to wage an

unequal contest against a

large

body

of Royalists. The Grantham

folk had much to say when

the troopers rode back

with

forty-five prisoners besides divers

horses and arms and colours. The

"Angel"

must

have seen all this and

sighed for peace. Grim

troopers paced its

corridors, and

its

stables were full of tired horses.

One owner of the inn at

the beginning of the

eighteenth

century, though he kept a

hostel, liked not

intemperance. His name

was

Michael

Solomon, and he left an

annual charge of 40s. to be paid to the

vicar of the

parish

for preaching a sermon in

the parish church against

the sin of

drunkenness.

The

interior of this ancient

hostelry has been modernized

and fitted with the

comforts

which we modern folk are

accustomed to expect.

Across

the way is the "Angel's"

rival the "George," possibly

identical with the

hospitium

called "Le George" presented

with other property by

Edward IV to his

mother,

the Duchess of York. It lacks

the appearance of age which

clothes the

"Angel"

with dignity, and was

rebuilt with red brick in

the Georgian era.

The

coaches

often called there, and

Charles Dickens stayed the

night and describes it as

one

of the best inns in England.

He tells of Squeers conducting

his new pupils

through

Grantham to Dotheboys Hall, and

how after leaving the

inn the luckless

travellers

"wrapped themselves more

closely in their coats and

cloaks ... and

prepared

with many half-suppressed moans again to

encounter the piercing

blasts

which

swept across the open

country." At the "Saracen's

Head" in Westgate Isaac

Newton

used to stay, and there are

many other inns, the

majority of which

rejoice

in

signs that are blue. We see

a Blue Horse, a Blue Dog, a

Blue Ram, Blue

Lion,

Blue

Cow, Blue Sheep, and many

other cerulean animals and

objects, which

proclaim

the political colour of the

great landowner. Grantham boasts of a

unique

inn-sign.

Originally known as the

"Bee-hive," a little public-house in

Castlegate has

earned

the designation of the

"Living Sign," on account of

the hive of bees fixed

in

a

tree that guards its portals.

Upon the swinging sign

the following lines

are

inscribed:--

Stop,

traveller, this wondrous

sign explore,

And

say when thou hast viewed it

o'er and o'er,

Grantham,

now two rarities are

thine--

A

lofty steeple and a "Living

Sign."

The

connexion of the "George"

with Charles Dickens reminds

one of the numerous

inns

immortalized by the great novelist

both in and out of London.

The "Golden

Cross"

at Charing Cross, the "Bull" at

Rochester, the "Belle Sauvage"

(now

demolished)

near Ludgate Hill, the

"Angel" at Bury St. Edmunds,

the "Great White

Horse"

at Ipswich, the "King's

Head" at Chigwell (the

original of the "Maypole"

in

Barnaby

Rudge), the

"Leather Bottle" at Cobham

are only a few of those

which he

by

his writings made

famous.

A

Quaint Gable. The Bell

Inn, Stilton

Leaving

Grantham and its inns, we

push along the great North

Road to Stilton,

famous

for its cheese, where a

choice of inns awaits

us--the "Bell" and

the

"Angel,"

that glare at each other

across the broad thoroughfare. In

the palmy days

of

coaching the "Angel" had

stabling for three hundred

horses, and it was kept by

Mistress

Worthington, at whose door

the famous cheeses were

sold and hence

called

Stilton, though they were

made in distant farmsteads and villages.

It is quite

a

modern-looking inn as compared with

the "Bell." You can see a

date inscribed on

one

of the gables, 1649, but

this can only mean that

the inn was restored then,

as

the

style of architecture of "this dream in

stone" shows that it must

date back to

early

Tudor times. It has a noble

swinging sign supported by

beautifully designed

ornamental

ironwork, gables, bay-windows, a Tudor

archway, tiled roof, and

a

picturesque

courtyard, the silence and

dilapidation of which are

strangely

contrasted

with the continuous bustle,

life, and animation which

must have existed

there

before the era of

railways.

Not

far away is Southwell, where

there is the historic inn

the "Saracen's Head."

Here

Charles I stayed, and you can see

the very room where he

lodged on the left of

the

entrance-gate. Here it was on

May 5th, 1646, that he gave

himself up to the

Scotch

Commissioners, who wrote to

the Parliament from

Southwell "that it

made

them

feel like men in a dream."

The "Martyr-King" entered this

inn as a sovereign;

he

left it a prisoner under the

guard of his Lothian escort.

Here he slept his

last

night

of liberty, and as he passed under

the archway of the

"Saracen's Head" he

started

on that fatal journey that

terminated on the scaffold at

Whitehall. You can

see

on the front of the inn

over the gateway a stone

lozenge with the royal

arms

engraved

on it with the date 1693,

commemorating this royal

melancholy visit. In

later

times Lord Byron was a

frequent visitor.

On

the high, wind-swept road

between Ashbourne and Buxton

there is an inn which

can

defy the attacks of the

reformers. It is called the

Newhaven Inn and was

built

by

a Duke of Devonshire for the

accommodation of visitors to Buxton.

King

George

IV was so pleased with it that he gave

the Duke a perpetual

licence, with

which

no Brewster Sessions can interfere.

Near Buxton is the second

highest inn in

England,

the "Cat and Fiddle," and

"The Traveller's Rest" at

Flash Bar, on the

Leek

road,

ranks as third, the highest

being the Tan Hill Inn, near

Brough, on the

Yorkshire

moors.

The

Bell Inn, Stilton

Norwich

is a city remarkable for its

old buildings and famous

inns. A very ancient

inn

is the "Maid's Head" at

Norwich, a famous hostelry

which can vie in

interest

with

any in the kingdom. Do we

not see there the

identical room in which

good

Queen

Bess is said to have reposed

on the occasion of her visit to

the city in 1578?

You

cannot imagine a more

delightful old chamber, with

its massive beams,

its

wide

fifteenth-century fire-place, and its

quaint lattice, through

which the

moonbeams

play upon antique furniture

and strange, fantastic carvings. This

oak-

panelled

room recalls memories of the

Orfords, Walpoles, Howards,

Wodehouses,

and

other distinguished guests

whose names live in

England's annals. The old

inn

was

once known as the Murtel or

Molde Fish, and some have

tried to connect the

change

of name with the visit of

Queen Elizabeth; unfortunately

for the conjecture,

the

inn was known as the Maid's

Head long before the days of

Queen Bess. It was

built

on the site of an old bishop's palace, and in

the cellars may be seen

some

traces

of Norman masonry. One of

the most fruitful sources of

information about

social

life in the fifteenth

century are the Paston

Letters. In one

written by John

Paston

in 1472 to "Mestresse Margret Paston," he tells

her of the arrival of a

visitor,

and

continues: "I praye yow make

hym goode cheer ... it were

best to sette hys

horse

at the Maydes Hedde, and I shall be

content for ther expenses."

During the

Civil

War this inn was the

rendezvous of the Royalists,

but alas! one day

Cromwell's

soldiers made an attack on

the "Maid's Head," and took

for their prize

the

horses of Dame Paston stabled

here.

We

must pass over the records

of civic feasts and aldermanic

junketings, which

would

fill a volume, and seek out

the old "Briton's Arms," in

the same city, a

thatched

building of venerable appearance

with its projecting upper

storeys and

lofty

gable. It looks as if it may not

long survive the march of

progress.

The

parish of Heigham, now part

of the city of Norwich, is

noted as having been

the

residence of Bishop Hall,

"the English Seneca," and

author of the Meditations,

on

his ejection from the

bishopric in 1647 till his death in

165643

The house

in

which

he resided, now known as the

Dolphin Inn, still stands, and is an

interesting

building

with its picturesque bays and

mullioned windows and ingeniously

devised

porch.

It has actually been

proposed to pull down, or

improve out of existence,

this

magnificent

old house. Its front is a

perfect specimen of flint and stone

sixteenth-

century

architecture. Over the main

door appears an episcopal coat of arms

with the

date

1587, while higher on the

front appears the date of a

restoration (in two

bays):

--

The

"Briton's Arms, "

Norwich

Just

inside the doorway is a fine

Gothic stoup into which

bucolic rustics now

knock

the

fag-ends of their pipes. The

staircase newel is a fine

piece of Gothic

carving

with

an embattled moulding, a poppy-head

and heraldic lion. Pillared

fire-places

and

other tokens of departed

greatness testify to the

former beauty of this

old

dwelling-place.

The

Dolphin Inn, Heigham,

Norwich

We

will now start back to town by

the coach which leaves the

"Maid's Head" (or

did

leave in 1762) at half-past

eleven in the forenoon, and hope to

arrive in London

on

the following day, and

thence hasten southward to Canterbury.

Along this Dover

road

are some of the best

inns in England: the "Bull"

at Dartford, with its

galleried

courtyard,

once a pilgrims' hostel; the

"Bull" and "Victoria" at

Rochester,

reminiscent

of Pickwick;

the modern "Crown" that

supplants a venerable inn

where

Henry

VIII first beheld Anne of

Cleves; the "White Hart";

and the "George,"

where

pilgrims

stayed; and so on to Canterbury, a city

of memories, which happily

retains

many

features of old English life

that have not altogether

vanished. Its grand

cathedral,

its churches, St.

Augustine's College, its

quaint streets, like

Butchery

Lane,

with their houses bending

forward in a friendly manner to

almost meet each

other,

as well as its old inns,

like the "Falstaff" in High

Street, near West

Gate,

standing

on the site of a pilgrims' inn,

with its sign showing

the valiant and

portly

knight,

and supported by elaborate ironwork, its

tiled roof and picturesque

front, all

combine

to make Canterbury as charming a place of

modern pilgrimage as it

was

attractive

to the pilgrims of another

sort who frequented its

inns in days of yore.

Shield

and Monogram on doorway of the

Dolphin Inn, Heigham

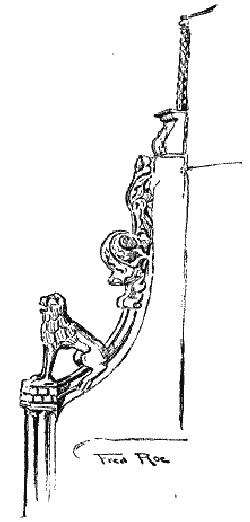

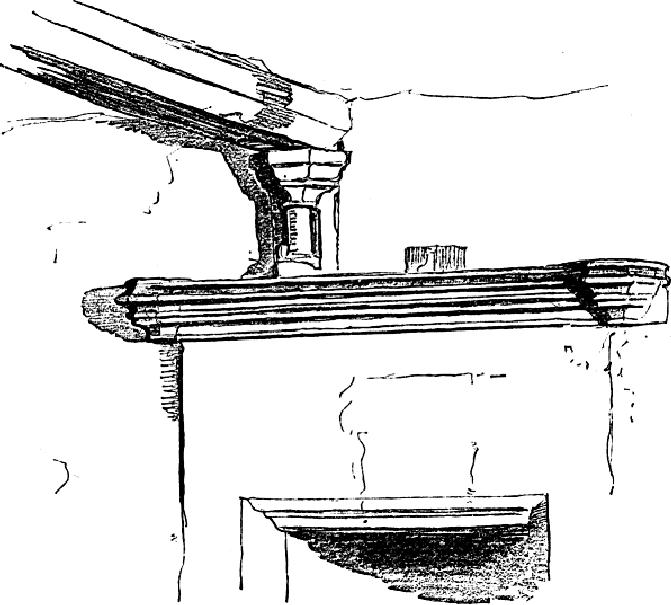

Staircase

Newel at the Dolphin Inn.

From Old

Oak Furniture, by Fred

Roe

And

now we will discard the cumbersome old

coaches and even the

"Flying

Machines,"

and travel by another flying

machine, an airship, landing

where we

will,

wherever a pleasing inn

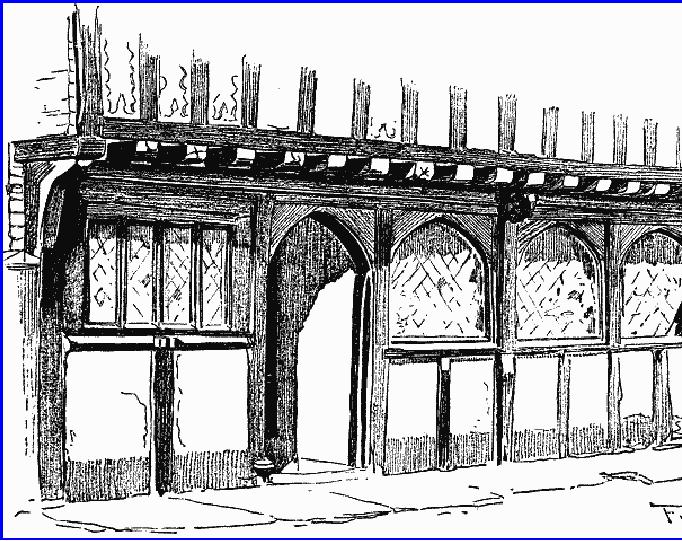

attracts us. At Glastonbury is

the famous "George,"

which

has hardly changed its

exterior since it was built by Abbot

Selwood in 1475

for

the accommodation of middle-class

pilgrims, those of high degree

being

entertained

at the abbot's lodgings. At

Gloucester we find ourselves in

the midst of

memories

of Roman, Saxon, and

monastic days. Here too are

some famous inns,

especially

the quaint "New Inn," in

Northgate Street, a somewhat peculiar

sign for

a

hostelry built (so it is said) for

the use of pilgrims

frequenting the shrine

of

Edward

II in the cathedral. It retains

all its ancient medieval

picturesqueness. Here

the

old gallery which surrounded

most of our inn-yards

remains. Carved beams

and

door-posts

made of chestnut are seen

everywhere, and at the corner of

New Inn

Lane

is a very elaborate sculpture, the

lower part of which

represents the Virgin

and

Holy Child. Here, in Hare

Lane, is also a similar inn,

the Old Raven

Tavern,

which

has suffered much in the

course of ages. It was formerly built

around a

courtyard,

but only one side of it is

left.

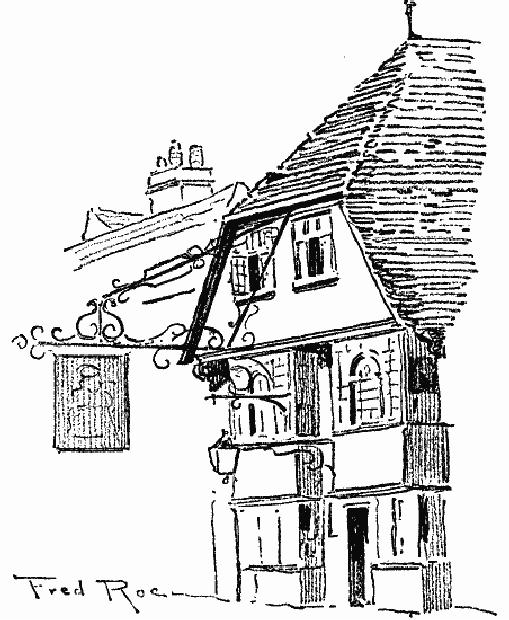

The

Falstaff Inn,

Canterbury

There

are many fine examples of

old houses that are

not inns in

Gloucester,

beautiful

half-timbered black and white

structures, such as Robert

Raikes's house,

the

printer who has the

credit of founding the first

Sunday-school, the old

Judges'

House

in Westgate Street, the old

Deanery with its Norman

room, once the

Prior's

Lodge

of the Benedictine Abbey.

Behind many a modern front

there exist curious

carvings

and quaintly panelled rooms

and elaborate ceilings. There is an

interesting

carved-panel

room in the Tudor House,

Westgate Street. The panels are of

the linen

-fold

pattern, and at the head of

each are various designs,

such as the Tudor

Rose

and

Pomegranate, the Lion of England,

etc. The house originally

known as the Old

Blue

Shop has some magnificent

mantelpieces, and also St. Nicholas

House can

boast

of a very elaborately carved

example of Elizabethan

sculpture.

We

journey thence to Tewkesbury and

visit the grand silver-grey

abbey that adorns

the

Severn banks. Here are

some good inns of great

antiquity. The "Wheat-sheaf"

is

perhaps

the most attractive, with

its curious gable and

ancient lights, and even

the

interior

is not much altered. Here

too is the "Bell," under

the shadow of the

abbey

tower.

It is the original of Phineas

Fletcher's house in the novel

John

Halifax,

Gentleman.

The "Bear and the Ragged

Staff" is another half-timbered house

with a

straggling

array of buildings and

curious swinging signboard,

the favourite haunt

of

the

disciples of Izaak Walton,

under the overhanging eaves

of which the Avon

silently

flows.

The

old "Seven Stars" at Manchester is

said to be the most ancient

in England,

claiming

a licence 563 years old. But it

has many rivals, such as

the "Fighting

Cocks"

at St. Albans, the "Dick

Whittington" in Cloth Fair,

St. Bartholomews, the

"Running

Horse" at Leatherhead, wherein

John Skelton, the poet

laureate of Henry

VIII,

sang the praises of its

landlady, Eleanor Rumming, and

several others. The

"Seven

Stars" has many interesting features

and historical associations. Here

came

Guy

Fawkes and concealed himself in "Ye Guy

Faux Chamber," as the legend

over

the

door testifies. What strange stories

could this old inn

tell us! It could tell us

of

the

Flemish weavers who, driven

from their own country by

religious persecutions

and

the atrocities of Duke Alva,

settled in Manchester in 1564, and

drank many a

cup

of sack at the "Seven

Stars," rejoicing in their

safety. It could tell us of

the

disputes

between the clergy of the

collegiate church and the

citizens in 1574,

when

one

of the preachers, a bachelor of divinity,

on his way to the church was

stabbed

three

times by the dagger of a

Manchester man; and of the

execution of three

popish

priests, whose heads were

afterwards exposed from the

tower of the church.

Then

there is the story of the

famous siege in 1642, when

the King's forces tried

to

take

the town and were repulsed

by the townsfolk, who were

staunch Roundheads.

"A

great and furious skirmish did

ensue," and the "Seven Stars"

was in the centre of

the

fighting. Sir Thomas Fairfax

made Manchester his head-quarters in

1643, and

the

walls of the "Seven Stars"

echoed with the carousals of

the Roundheads. When

Fairfax

marched from Manchester to

relieve Nantwich, some dragoons had to

leave

hurriedly,

and secreted their mess

plate in the walls of the

old inn, where it was

discovered

only a few years ago, and

may now be seen in the

parlour of this

interesting

hostel. In 1745 it furnished

accommodation for the

soldiers of Prince

Charles

Edward, the Young Pretender,

and was the head-quarters of

the Manchester

regiment.

One of the rooms is called

"Ye Vestry," on account of its

connexion with

the

collegiate church. It is said

that there was a secret

passage between the inn

and

the

church, and, according to

the Court Leet Records, some

of the clergy used to

go

to

the "Seven Stars" in sermon-time in

their surplices to refresh

themselves. O

tempora!

O mores! A horseshoe

at the foot of the stairs

has a story to tell.

During

the

war with France in 1805 the

press-gang was billeted at the

"Seven Stars." A

young

farmer's lad was leading a horse to be

shod which had cast a shoe. The

press-

gang

rushed out, seized the

young man, and led him

off to serve the king.

Before

leaving

he nailed the shoe to a post on

the stairs, saying, "Let

this stay till I come

from

the wars to claim it." So it

remains to this day

unclaimed, a mute reminder

of

its

owner's fate and of the

manners of our

forefathers.

The

Bear and Ragged Staff Inn,

Tewkesbury

Another

inn, the "Fighting Cocks" at

St. Albans, formerly known

as "Ye Old

Round

House," close to the River

Ver, claims to be the oldest

inhabited house in

England.

It probably formed part of

the monastic buildings, but

its antiquity as an

inn

is not, as far as I am aware, fully

established.

The

antiquary must not forget

the ancient inn at

Bainbridge, in Wensleydale,

which

has

had its licence since 1445, and

plays its little part in

Drunken

Barnaby's

Journal.

Fire-place

in the George Inn, Norton

St. Philip, Somerset

Many

inns have played an

important part in national

events. There is the "Bull"

at

Coventry,

where Henry VII stayed before

the battle of Bosworth

Field, where he

won

for himself the English

crown. There Mary Queen of

Scots was detained by

order

of Elizabeth. There the

conspirators of the Gunpowder

Plot met to devise

their

scheme for blowing up the

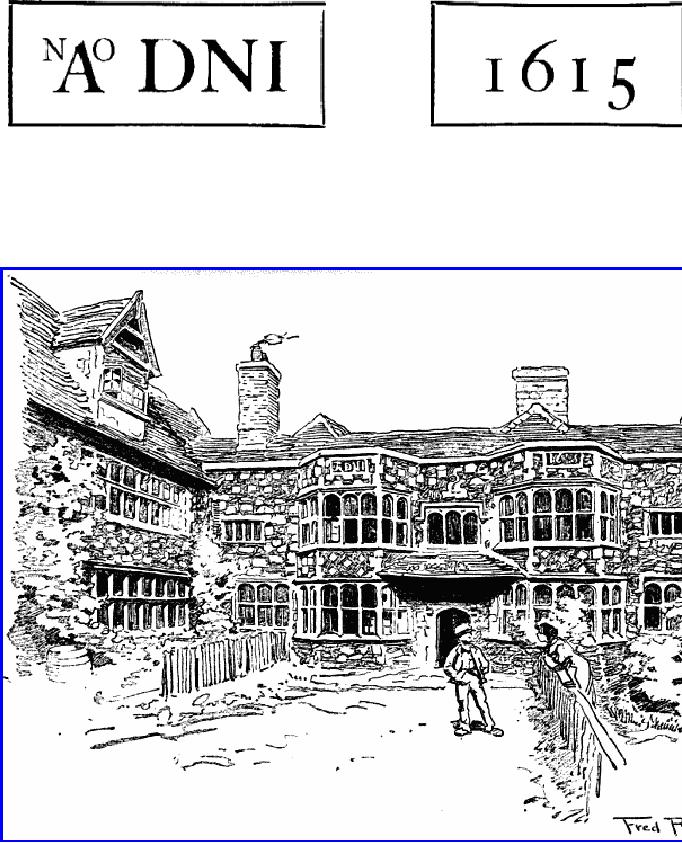

Houses of Parliament. The George Inn at

Norton

St.

Philip, Somerset, took part in

the Monmouth rebellion.

There the Duke

stayed,

and

there was much excitement in

the inn when he informed

his officers that it

was

his

intention to attack Bristol.

Thence he marched with his

rude levies to

Keynsham,

and after a defeat and a vain visit to

Bath he returned to the

"George"

and

won a victory over Faversham's advanced

guard. You can still see

the

Monmouth

room in the inn with

its fine fire-place.

The

Crown and Treaty Inn at Uxbridge

reminds one of the meeting of

the

Commissioners

of King and Parliament, who

vainly tried to arrange a peace

in

1645;

and at the "Bear," Hungerford,

William of Orange received

the

Commissioners

of James II, and set out

thence on his march towards

London and

the

English throne.

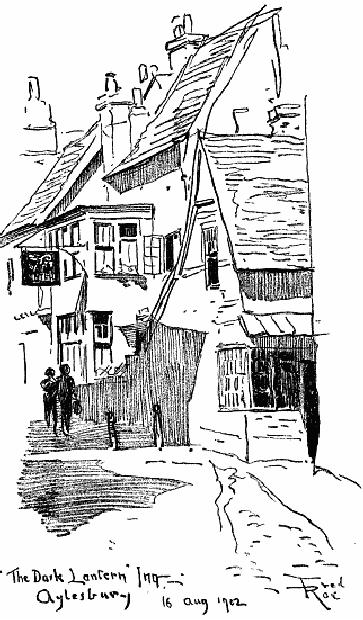

The

Dark Lantern Inn at Aylesbury, in a nest

of poor houses, seems to tell by

its

unique

sign of plots and conspiracies.

Aylesbury

is noted for its inns.

The famous "White Hart" is

no more. It has

vanished

entirely, having disappeared in

1863. It had been modernized,

but could

boast

of a timber balcony round

the courtyard, ornamented

with ancient wood

carvings

brought from Salden House, an

old seat of the Fortescues, near

Winslow.

Part

of the inn was built by

the Earl of Rochester in

1663, and many were

the great

feasts

and civic banquets that took place

within its hospitable doors.

The "King's

Head"

dates from the middle of

the fifteenth century and is a good

specimen of the

domestic

architecture of the Tudor

period. It formerly issued

its own tokens. It

was

probably

the hall of some guild or

fraternity. In a large window

are the arms of

England

and Anjou. The George Inn has

some interesting paintings

which were

probably

brought from Eythrope House

on its demolition in 1810, and

the "Bull's

Head"

has some fine beams and

panelling.

The

Green Dragon Inn, Wymondham,

Norfolk

Some

of the inns of Burford and

Shrewsbury we have seen when

we visited those

old-world

towns. Wymondham, once famous

for its abbey, is noted

for its "Green

Dragon,"

a beautiful half-timbered house with

projecting storeys, and in

our

wanderings

we must not forget to see

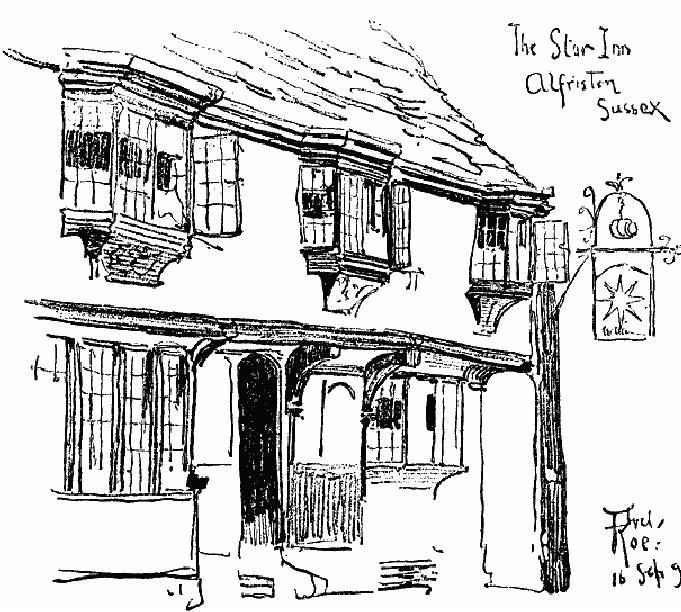

along the Brighton road the

picturesque

"Star"

at Alfriston with its three

oriel windows, one of the

oldest in Sussex. It was

once

a sanctuary within the

jurisdiction of the Abbot of

Battle for persons

flying

from

justice. Hither came

men-slayers, thieves, and rogues of every

description,

and

if they reached this

inn-door they were safe.

There is a record of a

horse-thief

named

Birrel in the days of Henry VIII seeking

refuge here for a crime

committed

at

Lydd, in Kent. It was

intended originally as a house for

the refreshment of

mendicant

friars. The house is very

quaint with its curious

carvings, including a

great

red lion that guards the side,

the figure-head of a wrecked

Dutch vessel lost in

Cuckmen

Haven. Alfriston was noted

as a great nest of smugglers, and the

"Star"

was

often frequented by Stanton

Collins and his gang, who

struck terror into

their

neighbours,

daringly carried on their

trade, and drank deep at the

inn when the

kegs

were

safely housed. Only fourteen

years ago the last of his

gang died in Eastbourne

Workhouse.

Smuggling is a vanished profession

nowadays, a feature of

vanished

England

that no one would seek to

revive. Who can tell whether

it may not be as

prevalent

as ever it was, if tariff

reform and the imposition of

heavy taxes on

imports

become articles of our

political creed?

The

Star Inn, Afriston

Sussex.

Many

of the inns once famous in

the annals of the road have

now "retired from

business"

and have taken down their

signs. The First and

Last Inn, at Croscombe,

Somerset,

was once a noted coaching

hostel, but since coaches

ceased to run it was

not

wanted and has closed its

doors to the public. Small

towns like Hounslow,

Wycombe,

and Ashbourne were full of important

inns which, being no

longer

required

for the accommodation of

travellers, have retired

from work and

converted

themselves

into private houses. Small

villages like Little

Brickhill, which

happened

to

be a stage, abounded with hostels

which the ending of the

coaching age made

unnecessary.

The Castle Inn at Marlborough, once one of

the finest in England,

is

now

part of a great public school.

The house has a noted

history. It was once a

nobleman's

mansion, being the home of

Frances Countess of Hereford, the

patron

of

Thomson, and then of the

Duke of Northumberland, who

leased it to Mr.

Cotterell

for the purpose of an inn.

Crowds of distinguished folk

have thronged its

rooms

and corridors, including the great

Lord Chatham, who was laid

up here with

an

attack of gout for seven weeks in 1762

and made all the

inn-servants wear his

livery.

Mr. Stanley Weyman has made

it the scene of one of his

charming

romances.

It was not until 1843 that it

took down its sign, and

has since patiently

listened

to the conjugation of Greek and

Latin verbs, to classic lore, and

other

studies

which have made Marlborough

College one of the great and

successful

public

schools. Another great inn was

the fine Georgian house near one of

the

entrances

to Kedleston Park, built by Lord

Scarsdale for visitors to

the medicinal

waters

in his park. But these

waters have now ceased to

cure the mildest

invalid,

and

the inn is now a large

farm-house with vast stables

and barns.

It

seems as if something of the

foundations of history were

crumbling to read

that

the

"Star and Garter" at Richmond is to be

sold at auction. That is a

melancholy

fate

for perhaps the most

famous inn in the country--a

place at which princes and

statesmen

have stayed, and to which

Louis Philippe and his Queen

resorted. The

"Star

and Garter" has figured in

the romances of some of our

greatest novelists.

One

comes across it in Meredith and

Thackeray, and it finds its

way into numerous

memoirs,

nearly always with some

comment upon its unique

beauty of situation, a

beauty

that was never more real

than at this moment when

the spring foliage is

just

beginning

to peep.

The

motor and changing habits

account for the evil days

upon which the

hostelry

has

fallen. Trains and trams

have brought to the doors

almost of the "Star

and

Garter"

a public that has not

the means to make use of its

120 bedrooms. The richer

patrons

of other days flash past on

their motors, making for

those resorts higher up

the

river which are filling

the place in the economy of

the London Sunday and

week-end

which Richmond occupied in

times when travelling was

more difficult.

These

changes are inevitable. The

"Ship" at Greenwich has

gone, and Cabinet

Ministers

can no longer dine there.

The convalescent home, which

was the undoing

of

certain Poplar Guardians, is housed in an

hotel as famous as the

"Ship," in its

days

once the resort of Pitt and

his bosom friends. Indeed, a

pathetic history

might

be

written of the famous

hostelries of the

past.

Not

far from Marlborough is

Devizes, formerly a great coaching

centre, and full of

inns,

of which the most noted is

the "Bear," still a thriving

hostel, once the home

of

the

great artist Sir Thomas

Lawrence, whose father was

the landlord.

Courtyard

of the George Inn, Norton

St. Philip Somerset

It

is impossible within one chapter to

record all the old

inns of England, we

have

still

a vast number left

unchronicled, but perhaps a

sufficient number of

examples

has

been given of this important

feature of vanishing England.

Some of these are

old

and crumbling, and may die of old

age. Others will fall a prey

to licensing

committees.

Some have been left

high and dry, deserted by

the stream of guests

that

flowed

to them in the old coaching

days. Motor-cars have resuscitated some

and

brought

prosperity and life to the

old guest-haunted chambers. We cannot

dwell on

the

curious signs that greet us as we travel

along the old highways, or

strive to

interpret

their origin and meaning. We

are rather fond in Berkshire

of the "Five

Alls,"

the interpretation of which is

cryptic. The Five Alls

are, if I remember

right--

"I

rule all" [the

king].

"I

pray for all" [the

bishop].

"I

plead for all" [the

barrister].

"I

fight for all" [the

soldier].

"I

pay for all" [the

farmer].

One

of the most humorous inn

signs is "The Man Loaded with

Mischief," which is

found

about a mile from Cambridge,

on the Madingley road. The

original Mischief

was

designed by Hogarth for a

public-house in Oxford Street. It is

needless to say

that

the signboard, and even the

name, have long ago

disappeared from the

busy

London

thoroughfare, but the quaint

device must have been

extensively copied by

country

sign-painters. There is a "Mischief" at

Wallingford, and a "Load of

Mischief"

at Norwich, and another at Blewbury.

The inn on the Madingley

road

exhibits

the sign in its original

form. Though the colours

are much faded from

exposure

to the weather, traces of

Hogarthian humour can be detected. A man

is

staggering

under the weight of a woman,

who is on his back. She is

holding a glass

of

gin in her hand; a chain and

padlock are round the man's

neck, labelled

"Wedlock."

On the right-hand side is

the shop of "S. Gripe,

Pawnbroker," and a

carpenter

is just going in to pledge his

tools.

"The

Dark Lantern" Inn,

Aylesbury

The

art of painting signboards is almost

lost, and when they

have to be renewed

sorry

attempts are made to imitate

the old designs. Some celebrated

artists have not

thought

it below their dignity to

paint signboards. Some have done

this to show

their

gratitude to their kindly

host and hostess for favours

received when

they

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF ENGLAND

- OLD WALLED TOWNS

- IN STREETS AND LANES

- OLD CASTLES

- VANISHING OR VANISHED CHURCHES

- OLD MANSIONS

- THE DESTRUCTION OF PREHISTORIC REMAINS

- CATHEDRAL CITIES AND ABBEY TOWNS

- OLD INNS

- OLD MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS

- OLD CROSSES

- STOCKS AND WHIPPING-POSTS

- OLD BRIDGES

- OLD HOSPITALS AND ALMSHOUSES

- VANISHING FAIRS

- THE DISAPPEARANCE OF OLD DOCUMENTS

- OLD CUSTOMS THAT ARE VANISHING

- THE VANISHING OF ENGLISH SCENERY

- CONCLUSION