|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

34

Restructuring

Organizations

We begin to

examine techno-structural interventions

change programs focusing on the

technology and

structure

of organizations. Increasing global

competition and rapid technological

and environmental

changes

are forcing organizations to

restructure themselves from

rigid bureaucracies to leaner

more flexible

structures.

These new forms of organizing are

highly adaptive and cost

efficient. They often result in

fewer

managers

and employees and iii

streamlined work flows that

break down functional

barriers.

Interventions

aimed at structural design include moving

from more traditional ways

of dividing the

organization's

overall work, such as

functional, self-contained-unit and

matrix structures, to

more

integrative

and flexible forms, such as

process-based and network-based

structures. Diagnostic guidelines

help

determine which structure is appropriate

for particular organizational environments,

technologies, and

conditions.

Downsizing

seeks to reduce costs and

bureaucracy by decreasing the size of the

organization. This

reduction

in personnel can be accomplished

through layoffs, organization redesign,

and outsourcing, which

involves

moving functions that are

not part of the organization's core

competence to outside

contractors.

Successful

downsizing is closely aligned with the

organization's strategy.

Reengineering

radically redesigns the organization's

core work processes to give

tighter linkage and

coordination

among the different tasks. This

work-flow integration results in

faster, more responsive

task

performance.

Reengineering often is accomplished

with new information technology

that permits

employees

to control and coordinate work

processes more

effectively.

Structural

Design:

Organization

structure describes how the

overall work of the organization is

divided into subunits and

how

these

subunits are coordinated for

task completion It is a key

feature of an organization's

strategic

orientation.

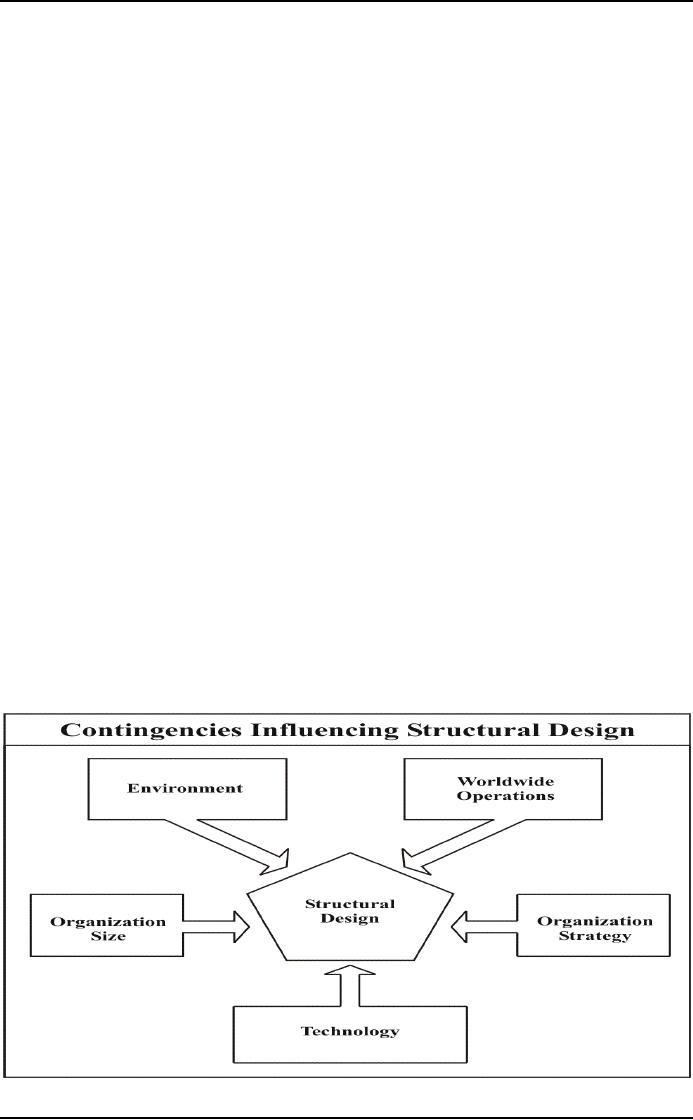

Based on a contingency perspective shown

in Figure 41, organization structures should

be

designed

to fit with at least five

factors: the environment, organization

size, technology, organization

strategy

and worldwide operations. Organization

effectiveness depends on the extent to

which its structures

are

responsive to these

contingencies.

Organizations

traditionally have structured

themselves into one of three

forms: functional departments

that

are

task specialized; self-contained units

that are oriented to

specific products, customers, or

regions; or

matrix

structures that combine both

functional specialization and

self-containment. Faced with

accelerating

changes

in competitive environments and

technologies, however, organizations

increasingly have

redesigned

their structures into more

integrative and flexible forms. These

more recent innovations

include

process-based

structures that design

subunits around the organization's core

work processes, and

network-

based

structures that link the organization to

other, interdependent organizations. The

advantages,

disadvantages,

and contingencies of the different

structures are described

below.

Figure

41. Contingencies Influencing

Structural Design

The

Functional Organization:

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

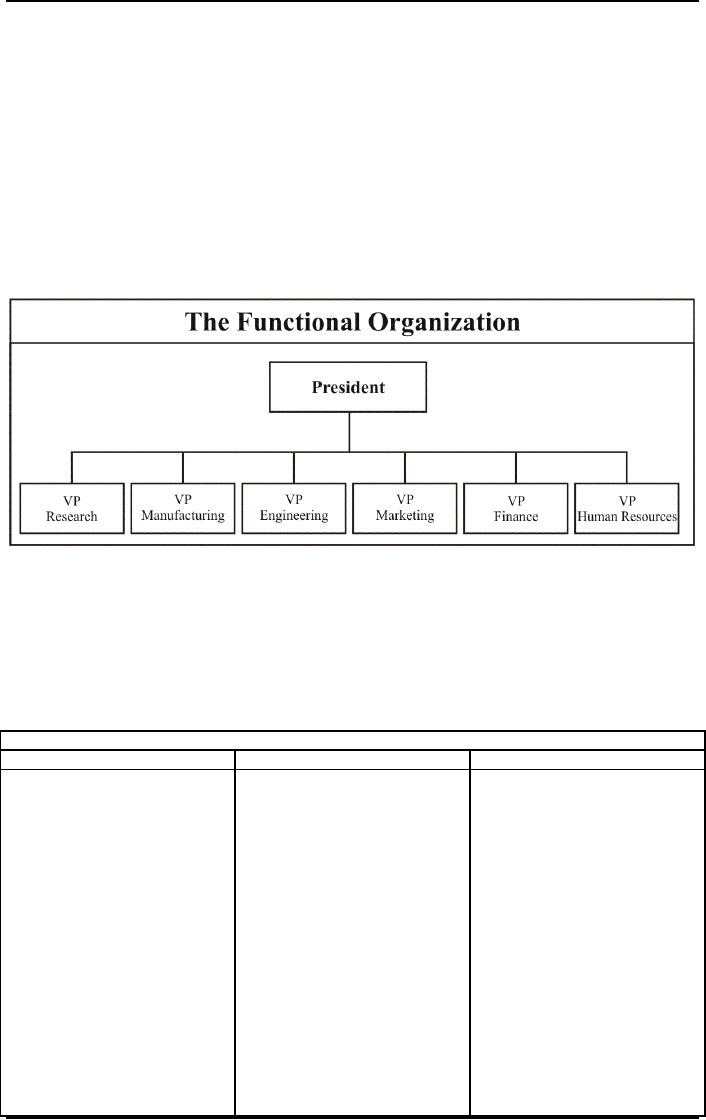

Perhaps

the most widely used organizational

structure in the world today is the basic

functional structure,

depicted

in figure 42. The organization

usually is subdivided into functional

units, such as engineering,

research,

operation, human resources,

finance, and marketing. This

structure is based on early

management

theories

regarding specialization line

and staff relations, span of control,

authority, and responsibility.

The

major

functional subunits are

staffed by specialists in such

disciplines as engineering and

accounting. It is

considered

easier to manage specialists if they

are grouped together under the same head

and if the head of

the

department has training and

experience in that particular

discipline.

Table

12 lists the advantages and

disadvantages of functional structures.

On the positive side, functional

structures

promote specialization of skills

and resources by grouping people

who perform similar work

and

face

similar problems. This grouping

facilitates communication within

departments and allows

specialists to

share

their expertise. It also

enhances career development within the

specialist, whether it is

accounting,

finance,

engineering, or sales. The

functional structure reduces

duplication of services because it

makes the

best

use of people and

resources.

Figure

42. The Functional

Organization

On

the negative side, functional

structures tend to promote

routine tasks with a limited

orientation.

Department

members focus on their own

tasks, rather than on the organization's

total task. This can

lead

to

conflict across functional

departments when each group

tries to maximize its own

performance without

considering

the performance of other units.

Coordination and scheduling

among departments can

be

difficult

when each emphasizes its

own perspective. As shown in

Table 12, the functional

structure tends to

work

best in small-to medium-sized firms in environments

that are relatively stable

and certain. These

organizations

typically have a small number of products

or services, and coordination

across specialized

units

is relatively easy. This structure

also is best suited to

routine technologies in which

there is

interdependence

within functions, arid to organizational goals

emphasizing efficiency and technical

quality.

Table

12: Advantages, Disadvantages, and

Contingencies of the Functional

Form

Advantages

Disadvantages

Contingencies

�

Emphasizes

�

Stable

�

routine

and

certain

Promotes

skill

�

tasks,

which encourages

environment

specialization

�

Small

to medium size

short

time horizons

�

Reduces

duplication of

�

Fosters

�

Routine

parochial

technology,

scarce

resources and uses

perspectives

by

interdependence

within

resources

full time

managers,

which limit

�

functions

Enhances

career

their

capabilities for top-

�

Goals

of efficiency and

development

for

management

positions

technical

quality

specialists

within large

�

Reduces

communication

departments

and

cooperation between

�

Facilitates

departments

communication

and

�

Multiplies

the

performance

because

interdepartmental

superiors

share expertise

dependencies,

which can

with

their subordinates

make

coordination and

�

Exposes

specialists to

scheduling

difficult

others

within the same

�

Obscures

accountability

specialty

for

overall outcomes

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

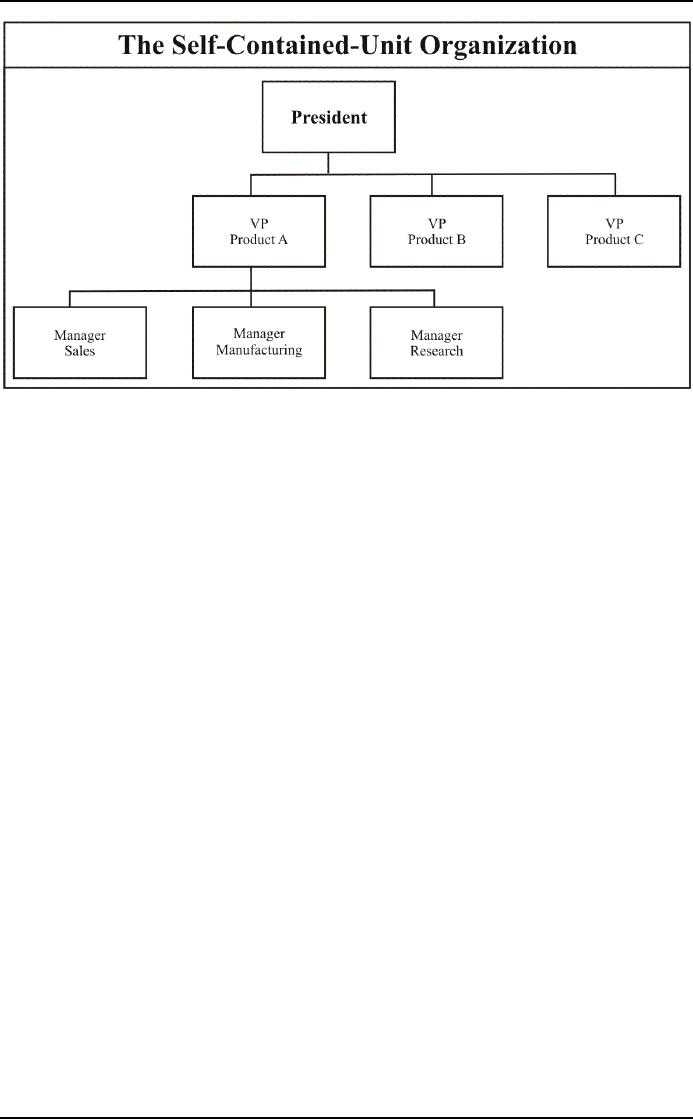

The

Self-Contained-Unit Organization:

The

self-contained-unit structure represents fundamentally

different way of organizing. Also

known as a

product

or divisional structure, it

was developed at about the same time by

General Motors, Sears,

Standard

Oil of New Jersey (Exxon),

and DuPont. It groups organizational

activities on the basis of

products,

services, customers, or geography.

All or most of the resources

necessary to accomplish a

specific

objective

are set up as a self-contained

unit headed by a product or

division manager. For

example, General

Electric

has plants that specialize

in making jet engines and

others that produce household

appliances. Each

plant

manager reports to a particular division or

product vice president, rather

than to a manufacturing vice

president.

In effect, a large organization may set

up smaller (sometimes temporary) special

purpose

organizations,

each geared to a specific

product, service, customer, or region. A

typical product structure is

shown

in Figure 43. It is interesting to note that, the

formal structure within a

self-contained unit often

is

functional

in nature.

Table

13 lists the advantages and

disadvantages of self-contained-unit structures.

These organizations

recognize

key interdependencies and coordinate

resources toward an overall

outcome. This strong outcome

orientation

ensures departmental accountability and

promotes cohesion among

those contributing to the

product.

These structures provide

employees with opportunities

for learning new skills and

expanding

knowledge

because workers can move

more easily among the

different specialties contributing to

the

product.

As a result, self-contained-unit structures

are well suited for

developing general managers.

Self-

contained-unit

organizations do have certain

problems. They may not have

enough specialized work to

use

people's

skills and abilities fully.

Specialists may feel isolated

from their professional

colleagues and may

fai1

to

advance in their career

specialty. The structures

may promote allegiance to department

rather than

organization

objectives. They also place

multiple demands on people, thereby

creating stress.

Table

13

Advantages,

Disadvantages and contingencies of the

Self-Contained-unit Form

Advantages

Disadvantages

Contingencies

�

Unstable

and uncertain

�

May

use skills

and

�

Recognizes

sources of

�

environments

resources

inefficiently

interdepartmental

�

Large

size

�

Limits

dependencies

career

�

Technological

�

advancement

by

fosters

an orientation

specialists

to movements

interdependence

across

toward

overall outcomes

out

of their departments

functions

and

clients

�

Impedes

specialists

�

Goals

�

of

product

allows

diversification and

esposure

to others within

specialization

and

expansion

of skills and

the

same specialties

innovation

training

�

Puts

multiple-role

�

ensures

accountability by

demands

on people and

departmental

managers

so

creates stress

and

so

promotes

�

May

promote

delegation

of authority

departmental

objectives,

and

responsibility

�

as

opposed to overall

heightens

departmental

organizational

objectives

cohesion

and

involvement

in work

The

self-contained-unit structure works best in

conditions almost the opposite of those

favoring a

functional

organization, as shown in Table 13.

The organization needs to be relatively

large to support the

duplication

of' resources assigned to the units.

Because each unit is

designed to fit a particular niche,

the

structure

adapts well to uncertain conditions.

Self-contained units also help to

coordinate technical

interdependencies

falling across functions and

are suited to goals

promoting product or

service

specialization

and innovation.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

43: The Self-Contained-Unit

Organization

The

Matrix Organization:

Some

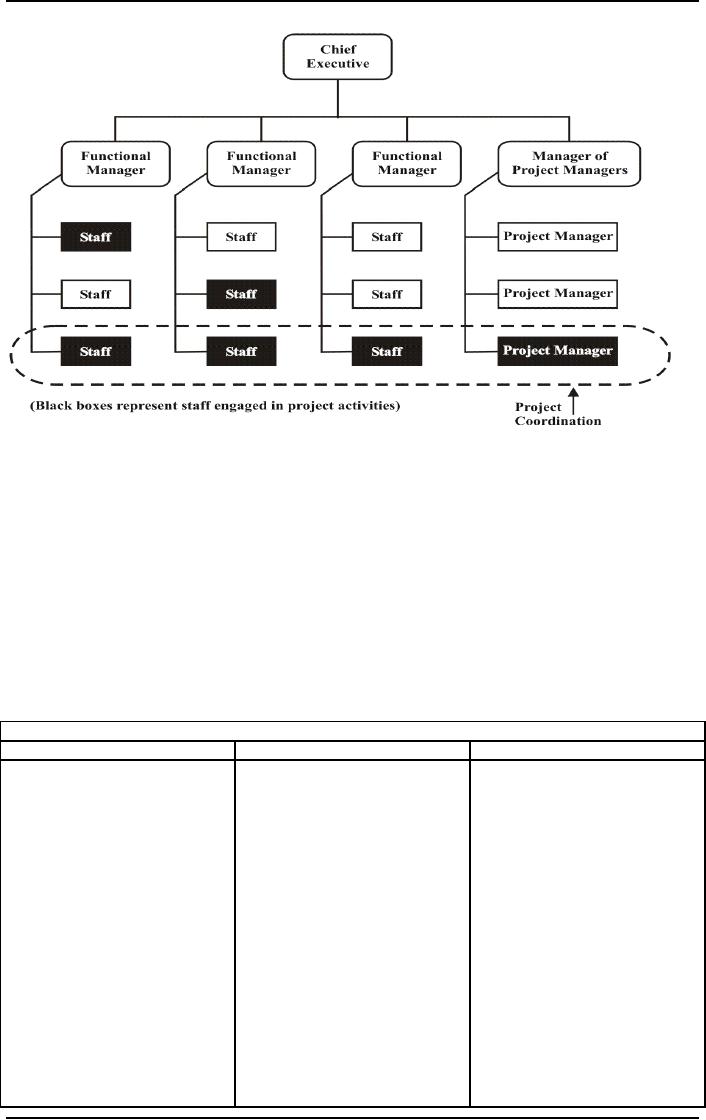

OD practitioners have focused on maximizing the

strengths and minimizing the

weaknesses of both

the

functional and the self-contained-unit

structures, and this effort

has resulted in the matrix

organization.

It

superimposes the lateral structure of a

product or project coordinator on the

vertical functional structure,

as

shown in Figure 44. Matrix organizational

designs originally evolved in the

aerospace industry

where

changing

customer demands and technological

conditions caused managers to

focus on lateral relationships

between

functions to develop a flexible and

adaptable system of resources

and procedures, and to

achieve a

series

of project objectives. Matrix

organizations now are used

widely in manufacturing, service,

and

nonprofit,

governmental, and professional

organizations.

Every

matrix organization contains three unique

and critical roles: the top

manager, who heads

and

balances

the dual chains of command, the matrix

bosses (functional, product, or

area), who share

subordinates:

and the two-boss managers,

who report to two different

matrix bosses. Each of these

roles

has

its own unique

requirements.

For

example, all engineers may

be in one engineering department and

report to an engineering

manager,

but

these same engineers may be

assigned to different projects

and report to a project

manager while

working

on that project. Therefore, each engineer

may have to work under

several managers to get his

or

her

job done.

In

a matrix organization, each project

manager reports directly to the vice

president and the

general

manager.

Since each project

represents a potential profit

centre, the power and authority

used by the

project

manager come directly from

the general manager.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

44. The Matrix

Organization

Matrix

organizations, like all organization

structures, have both

advantages and disadvantages, as

shown in

Table

14. On the positive side, this

structure allows multiple orientations.

Specialized, functional knowledge

can

be applied to all projects. New products

or projects can be implemented quickly by

using people

flexibly

and by moving between

product and functional orientations as

circumstances demand.

Matrix

organizations

can maintain consistency among

departments and projects by

requiring communication

among

managers. For many people,

matrix structures are

motivating and exciting.

On

the negative side, these

organizations can be difficult to

manage. To implement and maintain

them

requires

heavy managerial costs and

support. When people are assigned to

more than one

department,

there

may be role ambiguity and

conflict, and overall

performance may be sacrificed if

there are power

conflicts

between functional departments

and project structures. To

make matrix organizations

work,

organization

members need interpersonal and

conflict management skills.

People can get confused

about

how

the matrix works, and that

can lead to chaos and

inefficiencies

Table

14

Advantages,

Disadvantages and Contingencies of the

Matrix Form

Advantages

Disadvantages

contingencies

�

Make

�

Can

be very difficult

�

Dual

focus on unique

specialized,

introduce

without a

functional

knowledge

product

demands and

preexisting

supportive

available

to all projects.

technical

specialization

�

Uses

people flexibly,

�

Pressure

management

climate

for

high

�

Increases

role ambiguity,

because

departments

information

processing

stress

and anxiety by

maintain

reservoirs of

capacity

�

Pressure

for shared

assigning

people to more

specialists.

�

Maintains

than

one department

consistency

resources

�

Without

power balancing

between

different

between

product and

departments

and projects

functional

forms, lowers

by

forcing

communication

between

overall

performance

�

Makes

managers.

inconsistent

�

Recognizes

and provides

demands,

which may

mechanisms

for dealing

result

in unproductive

with

legitimate, multiple

conflicts

and short-term

sources

of power in the

crisis

management

�

May

reward political

organization.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

�

skills

as opposed

to

Can

adapt

to

technical

skills

environmental

changes

by

shifting emphasis

between

project and

functional

aspects

As

shown in Table 14, matrix

structures are appropriate under three

important conditions. First, there

must

be

outside pressures for a dual

focus. That is, a matrix

structure works best when there

are many customers

with

unique demands on the one hand and strong

requirements for technical sophistication

on the other

hand.

Second, a matrix organization is appropriate when the

organization must process a large amount

of

information.

Circumstances requiring such

capacity are few and include

the following: when external

environmental

demands change unpredictably and

there is considerable uncertainty in

decision making;

when

the organization produces a broad range of products or

services, or offers those outputs to a

large

number

of different markets, and

there is considerable complexity in

decision making: and when

there is

reciprocal

interdependence among the tasks in the

organization's technical core and

there is considerable

pressure

on communication and coordination

systems. Third, and finally,

there must be pressures

for

shared

resources. When customer

demands vary greatly and technological

requirements are strict,

valuable

human

and physical resources are

likely to be scarce. The

matrix works well under those

conditions because

in

facilitates the sharing of scarce

resources. If any of the foregoing

conditions is not met, a

matrix

organization

is likely to fail.

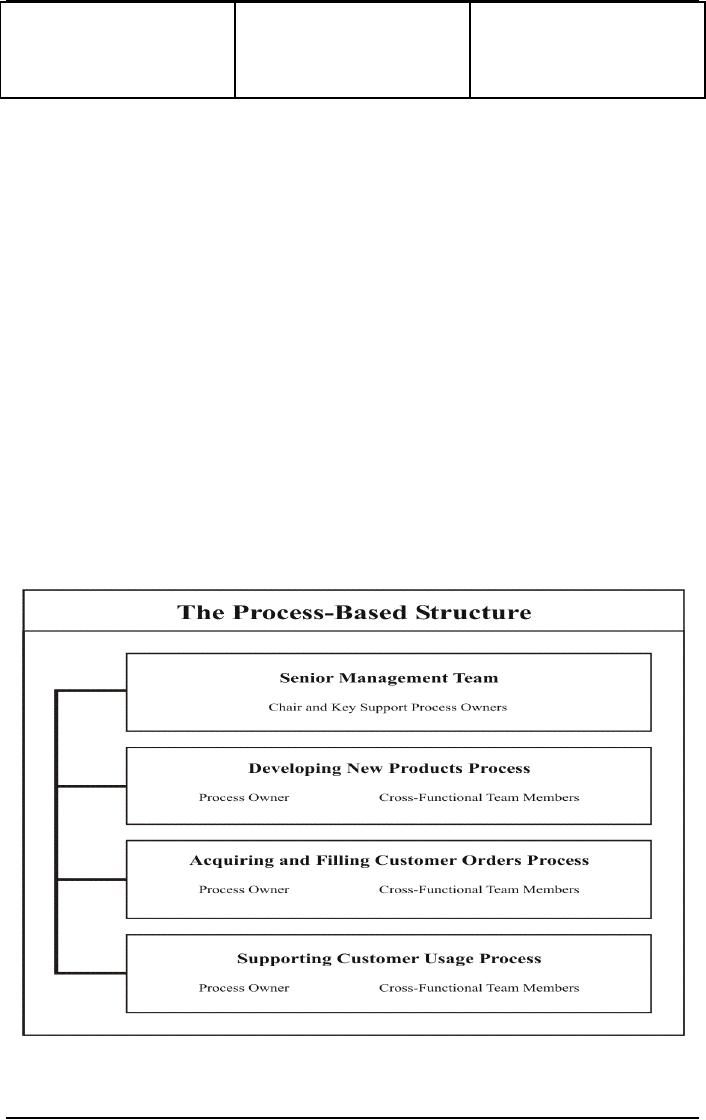

Process-Based

Structures:

A

radically new logic for structuring

organizations is to form

multidisciplinary teams around core

processes,

such

as product development, order

fulfillment, sales generation,

and customer support. As shown

in

Figure

45, process-based structures

emphasize lateral rather than vertical

relationships. All

functions

necessary

to produce a product or service

are placed in a common unit

usually managed by someone

called

a

"process owner." There are few

hierarchical levels, and the

senior executive team is relatively

small,

typically

consisting of the chair, the chief operating officer,

and the heads of a few key

support services

such

as strategic planning, human

resources, and

finance.

Figure

45: The Process-Based

Structure

Process-based

structures eliminate many of the

hierarchical and departmental

boundaries that can

impede

task

coordination and slow

decision making and task

performance. They reduce the enormous

costs of

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

managing

across departments up and

down the hierarchy. Process-based

structures enable organization to

focus

most of their resources on

serving customers, both

inside and outside the

firm.

The

use of process-based structures is

growing rapidly in a variety of manufacturing

and service

companies.

Typically

referred to as "horizontal" "boundary

less," or "team-based" organization, they are

used to

enhance

customer service at such

firm as American Express Financial Advisors,

The Associates, Duke

Power.

3M, Xerox, General Electric Capital

Services, at id the National b Provincial

building Society in

time

United Kingdom.

Although

there is no one right way to

design process- based

structures, the following features

characterize

this

new form of organizing.

Processes

drive structure. Process-based

structures are organized around the

three to five key

processes

that

define the work of the organization.

Rather than products or functions,

processes define the

structure

and

are governed by a "process owner."

Each process has clear

performance goals that drive

task

execution.

Work

adds value. To

increase efficiency, process--based

structures simplify and enrich

work processes.

Work

is simplified by eliminating nonessential

tasks and reducing layers of

management, and it is

enriched

by

combining tasks so that

learns perform whole

processes.

Teams

are fundamental. Teams

are the key organizing feature in a

process- based structure. They

manage

everything

from task execution to strategic

planning, are typically

self-managing, and are

responsible for

goal

achievement.

�

Customers

define performance. The

primary goal of any team in a

process-based structure is

customer

satisfaction.

Defining customer expectations

and designing team functions

to meet those

expectations

command

much of the team's attention.

The organization must value this

orientation as the primary path to

financial

performance.

Teams

are rewarded for

performance. Appraisal

systems focus on measuring

team performance

against

customer

satisfaction and other

goals, and then provide

real recognition for

achievement. Team-based

rewards

are given as much, if

not more, weight

than is individual

recognition.

Teams

are tightly linked to

suppliers and customers. Through

designated members, teams

have timely

and

direct relationships with vendors and

customers to understand and

respond to emerging

concerns.

Team

members are well informed and trained.

Successful

implementation of a process-based

structure

requires

team members who can

work with a broad range of

information, including customer

and market

data,

financial information, and

personnel and policy

matters. Team members also

need problem solving

and

decision-making skills and abilities to

address and implement solutions.

Table

15 lists

the advantages and disadvantages of

process-based structures. The

most frequently

mentioned

advantage is intense focus on

meeting customer needs,

which can result in

dramatic

improvements

in speed, efficiency, and customer

satisfaction. Process-based structures

remove layers of

management,

and consequently information

flows inure quickly and

accurately throughout the

organization.

Because process teams

comprise different functional

specialties, boundaries

between

departments

are removed, thus affording

organization members a broad view of the

work flow and a

clear

line

of sight between team

performance and organization

effectiveness. Process-based structures

also are

more

flexible and adaptable to

change than are traditional

structures.

Table

15: Advantages, Disadvantages, and

Contingencies of the Process-Based

Form

Advantages

Disadvantages

Contingencies

�

Focuses resources on customer �

Can threaten middle managers �

Uncertain and

changing

satisfaction

and

staff specialists

environments

�

Improves speed and efficiency, �

Requires changes in command- �

Moderate to large

size

often

dramatically

and-control

mindsets

�

Non-routine and

highly

�

Adapts to environmental change �

Duplicates scarce

resources

interdependent

technologies

rapidly

�

Requires new skills

and � Customer-oriented

goals

�

Reduces boundaries between knowledge

to manage

lateral

departments

relationships

and teams

�

Increases ability to see total �

May take longer to

make

work

flow

decisions

in teams

�

Enhances

employee

� Can be ineffective if

wrong

involvement

processes

are identified

�

Lowers costs because of

less

overhead

structure

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

A

major disadvantage of process-based

structures is the difficulty of changing

to this new organizational

form.

These structures typically require

radical shifts in mindsets,

skills, and managerial roles

-- changes

that

involve considerable time and

resources and can be

resisted by functional managers

and staff

specialists.

Moreover, process-based structures

may result in expensive

duplication of scarce resources

and,

if

teams are not skilled

adequately, in slower decision making as

they struggle to define and

reach

consensus.

Finally, implementing process-based

structures relies on properly

identifying key

processes

needed

to satisfy customer needs. If critical

processes are misidentified or ignored

altogether, performance

and

customer satisfaction are

likely to suffer.

Table

15 shows that process-based

structures are particularly appropriate

for highly uncertain environments

where

customer demands and market

conditions are changing

rapidly. They enable organizations to

manage

non-routine

technologies and coordinate work

flows that are highly

interdependent. Process-based

structures

generally appear in medium- to

large-sized organizations having several

products or projects.

They

focus heavily on customer-oriented goals

and are found in both

domestic and global

organizations.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information