|

PRACTICAL PROBLEMS |

| << VALUES |

| ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING >> |

CHAPTER

V

PRACTICAL

PROBLEMS

I

have thought it advisable in

this chapter to select, and to work

out in

some

detail, a few actual

problems in illustration, so as to

familiarize the

student

with the practical

application of some of the

principles

previously

laid down.

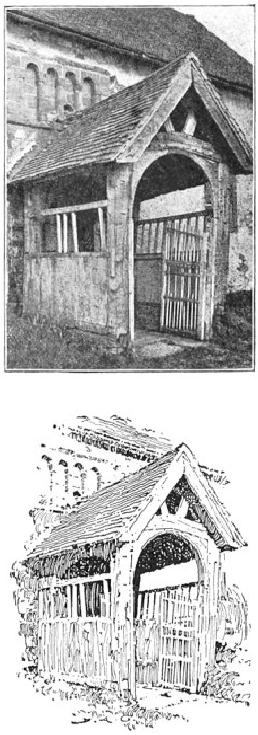

FIG.

35

FROM

A PHOTOGRAPH

FIG.

36

D.

A. GREGG

In

the first example the

photograph, Fig. 35, shows

the porch of an old

First

English

country church. Let us see

how this subject has

been interpreted Problem

in

pen and ink by Mr. D. A. Gregg, Fig.

36. In respect to the lines,

the

original

composition presents nothing

essentially unpleasant. Where

the

strong

accent of a picture occurs in the

centre, however, it is

generally

desirable

to avoid much emphasis at

the edges. For this

reason the pen

drawing

has been "vignetted,"--that is to

say, permitted to fade

away

irregularly

at the edges. Regarding the

values, it will be seen that

there is

no

absolute white in the

photograph. A literal rendering of

such low

color

would, as we saw in the preceding

chapter, be out of the

question;

and

so the essential values which

directly contribute to the

expression of

the

subject and which are

independent of local color or

accidental effect

have

to be sought out. We observe, then,

that the principal note of

the

photograph

is made by the dark part of

the roof under the

porch relieved

against

the light wall beyond.

This is the direct result of

light and shade,

and

is therefore logically adopted as

the principal note of Mr.

Gregg's

sketch

also. The wall at this point

is made perfectly white to

heighten the

contrast.

To still further increase

the light area, the

upper part of the

porch

has been left almost

white, the markings

suggesting the

construction

of the weather-beaten timber

serving to give it a faint

gray

tone

sufficient to relieve it from

the white wall. The

low color of the

grass,

were it rendered literally, would make

the drawing too heavy

and

uninteresting,

and this is therefore only

suggested in the sketch. The

roof

of

the main building, being

equally objectionable on account of

its mass

of

low tone, is similarly treated. Mr.

Gregg's excellent handling of

the

old

woodwork of the porch is

well worthy of study.

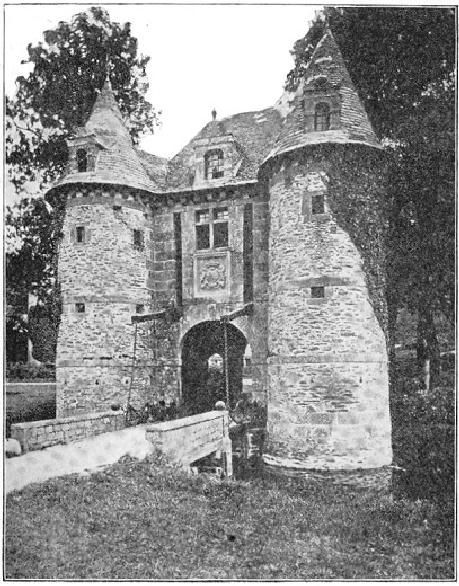

Let

us take another example. The

photograph in Fig. 37 shows a

moat- Second

house

in Normandy; and, except

that the low tones of the

foliage are Problem

exaggerated

by the camera, the

conditions are practically those

which we

would

have to consider were we

making a sketch on the spot.

First of all,

then,

does the subject, from

the point of view at which

the photograph is

taken,

compose well?* It cannot be

said that it does. The

vertical lines

made

by the two towers are

unpleasantly emphasized by the trees

behind

them.

The tree on the left were

much better reduced in height

and placed

somewhat

to the right, so that the

top should fill out the

awkward angles

of

the roof formed by the

junction of the tower and

the main building.

The

trees on the right might be

lowered also, but otherwise

permitted to

retain

their present relation. The

growth of ivy on the tower

takes an ugly

outline,

and might be made more

interestingly irregular in

form.

[Footnote

*: The student is advised to

consult "Composition," by Arthur W. Dow.

[New

York,

1898]]

FIG.

37

FROM

A PHOTOGRAPH

The

next consideration is the

disposition of the values. In

the

photograph

the whites are confined to

the roadway of the bridge

and the

bottom

of the tower. This is

evidently due, however, to

local color rather

than

to the direction of the

light, which strikes the

nearer tower from the

right,

the rest of the walls being

in shadow. While the black

areas of the

picture

are large enough to carry a

mass of gray without

sacrificing the

sunny

look, such a scheme would be

likely to produce a labored

effect.

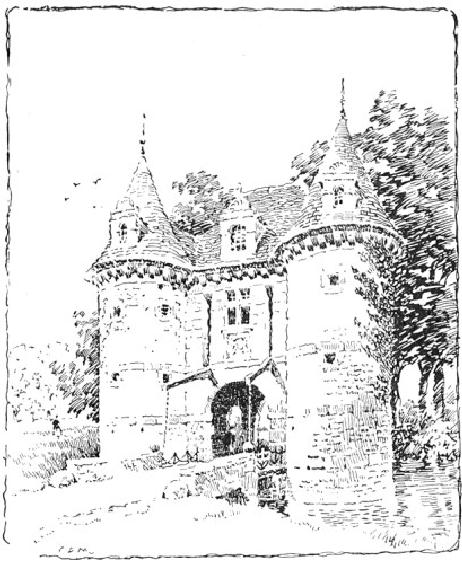

Two

alternative schemes readily

suggest themselves: First, to make

the

archway

the principal dark, the

walls light, with a light

half-tone for the

roof,

and a darker effect for the

trees on the right. Or,

second, to make

these

trees themselves the

principal dark, as suggested by

the

photograph,

allowing them to count against

the gray of the roof and

the

ivy

of the tower. This latter

scheme is that which has

been adopted in the

sketch,

Fig. 38.

FIG.

38

C.

D. M.

It

will be noticed that the

trees are not nearly so

dark as in the

photograph.

If they were, they would be

overpowering in so large an

area

of

white. It was thought better,

also, to change the direction of

the light,

so

that the dark ivy, instead of

acting contradictorily to the

effect, might

lend

character to the shaded

side. The lower portion of

the nearer tower

was

toned in, partly to qualify

the vertical line of the

tower, which would

have

been unpleasant if the

shading were uniform, and

partly to carry the

gray

around to the entrance. It was

thought advisable, also, to cut

from

the

foreground, raising the

upper limit of the picture

correspondingly. (It

is

far from my intention,

however, to convey the

impression that any

liberties

may be taken with a subject

in order to persuade it into

a

particular

scheme of composition; and in this

very instance an

artistic

photographer

could probably have discovered a

position for his

camera

which

would have obviated the

necessity for any change

whatever;--a

nearer

view of the building, for

one thing, would have

considerably

lowered

the trees.)

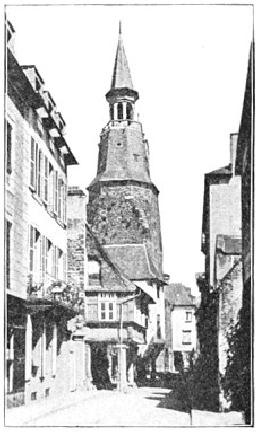

FIG.

39

FROM

A PHOTOGRAPH

We

will consider still another

subject. The photograph,

Fig. 39, shows Third

a

street in Holland. In this case,

the first thing we have to

determine is Problem

where

the interest of the subject

centres. In such a perspective the

salient

point

of the picture often lies in

a foreground building; or, if

the street be

merely

a setting for the

representation of some incident, in a

group of

foreground

figures. In either case the

emphasis should be placed in

the

foreground,

the distant vanishing lines

of the street being rendered

more

or

less vaguely. In the present

subject, however, the

converging sky and

street

lines are broken by the

quaint clock-tower. This and

the buildings

underneath

it appeal to us at once as the most

important elements of

the

picture.

The nearer buildings present nothing

intrinsically interesting,

and

therefore serve no better purpose than to

lead the eye to the centre

of

interest.

Whatever actual values these

intermediate buildings have

that

will

hinder their usefulness in

this regard can, therefore, be changed

or

actually

ignored without affecting

the integrity of the sketch

or causing

any

pangs of conscience.

The

building on the extreme left

shows very strong contrasts

of color in

the

black shadow of the eaves

and of the shop-front below.

These

contrasts,

coming as they do at the

edge of the picture, are

bad. They

would

act like a showy frame on a

delicate drawing, keeping

the eye

from

the real subject. It may be

objected, however, that it is

natural that

the

contrasts should be stronger in

the foreground. Yes; but in

looking

straight

at the clock-tower one does

not see any such

dark shadow at the

top

of the very uninteresting

building in the left

foreground. The

camera

saw

it, because the camera

with its hundred eyes

sees everything, and

does

not interest itself about

any one thing in particular.

Besides, if the

keeper

of the shop had the bad

taste to paint it dark we

are not bound to

make

a record of the fact; nor

need we assume that it was

done out of

regard

to the pictorial possibilities of

the street. We decide, therefore,

to

render,

as faithfully as we may, the

values of the clock-tower

and its

immediate

surroundings, and to disregard the

discordant elements; and

we

have no hesitation in selecting

for principal emphasis in

our drawing,

Fig.

40, the shadow under

the projecting building.

This dark accent will

count

brilliantly against the foreground

and the walls of the

buildings,

which

we will treat broadly as if white,

ignoring the slight

differences in

value

shown in the photograph. We

retain, however, the literal

values of

the

clock-tower and the buildings

underneath it, and express as

nearly as

we

can their interesting variations of

texture. The buildings on

the right

are

too black in the photograph,

and these, as well as the shadow

thrown

across

the street, we will considerably lighten.

After some

experiment,

we

find that the building on

the extreme left is a

nuisance, and we omit

it.

Even then, the one with

the balcony next to it

requires to be toned

down

in its strong values, and so

the shadows here are made

much

lighter,

the walls being kept

white. It will be found that

anything like a

strong

emphasis of the projecting

eaves of the building would

detract

from

the effect of the tower, so

that the shadow under

the eaves is,

therefore,

made grayer than in the

photograph, while that of

the balcony

below

is made stronger than the

shadow of the eaves, but is

lightened at

the

edge of the drawing to throw

the emphasis toward the

centre.