|

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC |

| << SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT |

| FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition >> |

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

44

SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

Aims:

·

To

understand the use of social psychology theories and

principles in clinical settings

Objectives:

·

To

discuss clinician's biases in

making clinical judgments

·

To

discuss the relationship of faulty

cognitions and mental and

physical illness

·

To

describe social-psychological approaches

to reverse the maladaptive patterns of

behavior

·

To

ascertain the relationship between

positive resources and

well-being

Chapter

Summary

This

chapter focuses on the social psychological

perspective on health and illness.

Health psychology is

based

on the biopsychosocial model, which

suggests that health and

illness are each multiply

determined by

biological,

psychological, and social factors. The

relationship between negative cognitions

and physical

and

mental health is discussed. Basic

attitudes that determine

health behaviors including

attitude toward

illness,

optimism vs. pessimism, and

explanatory styles are highlighted.

The importance of

positive

resources

and social support is reviewed in the

light of current research.

The ability of people to

recognize

their

physical symptoms is discussed as a

contributor to illness and

recovery. The interaction

between

patients

and practitioners is considered as a contributor to

low adherence to treatment programs,

and

interventions

that can improve adherence

are discussed. Discussing several methods

to reverse maladaptive

behaviors,

the chapter concludes by indicating that

the best treatment strategy is that patients

are equipped

with

the ability to have a control and mastery

over their negative

cognitions and maladapted

behavior.

Introduction:

Among

the many thriving areas of

applied social psychology is

one that relates social

psychology's

concepts

to depression, to other problems such as

loneliness, anxiety, and

physical illness, and now

to

happiness

and well-being. This bridge-building

research between social psychology

and clinical

psychology

seeks answers to four

important questions:

·

As

lay people or as professional

psychologists, how can we improve

our judgments and predictions

about

others?

·

How

can the ways in which we think

about self and others

feed such problems as

depression,

loneliness,

anxiety, and ill health?

·

How

might these maladaptive

thought patterns be

reversed?

·

What

part do close, supportive

relationships play in health and

happiness?

Making

clinical judgments

Social

psychologists are also interested to know

whether influences on our social

judgment also affect

clinicians'

judgments of clients. If so, what

biases should clinicians

(and their clients) be wary

of?

Is

Anjum suicidal? Should Ali be

admitted to a mental hospital? If

released Shaukat will be a

homicide

risk?

Facing such questions, clinical

psychologists struggle to make accurate

judgments, recommendations,

and

predictions.

Such

clinical judgments are also social

judgments and thus vulnerable to illusory

correlations,

overconfidence

bred by hindsight, and self-confirming

diagnoses. Professional clinicians are

"vulnerable to

insidious

errors and biases," concludes

James Maddux (1993).

Illusory

correlations

The

assumption here, as in so many clinical

judgments, is that test results

reveal something important.

Some

projective tests relate

people's responses (e.g.,

drawing big ears, bushy eyebrows,

pointed hands,

189

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

figure

without feet, etc.) with

suspiciousness, hostility, anger,

conflicts, insecurity, etc.

Some tests are

indeed

predictive. Others, such as a

projective test, "Draw-a-Person",

has correlations far weaker

than their

users

suppose. Why, then, do

clinicians continue to express

confidence in uninformative or

ambiguous

tests?

Pioneering

experiments by Loren Chapman and Jean

Chapman (1969, 1971) helped

us see why. They

invited

both college students and

professional clinicians to study

some test performances and

diagnoses. If

the

students or clinicians expected a

particular association they generally

perceived it, regardless of

whether

the

data were supportive. For

example, clinicians who

believed that suspicious

people draw peculiar

eyes

on

the Draw-a-Person test perceived

such

Hindsight

bias

It

has often been criticized

that the clinicians are too

readily convinced of their

own after-the-fact

analyses.

If

someone we know commits suicide,

how do we react? One common

reaction is to think that

we, or those

close

to the person, should have been

able to predict and therefore to

prevent the suicide: In hindsight,

we

can

see the suicidal signs and

the pleas for help. One

experiment gave people a description of a

depressed

person

who later committed suicide.

Compared to those not informed of the

suicide, those told the

person

committed

suicide were more likely to say

they "would have expected" it

(Goggin & Range,

1985).

Moreover,

if they were told of the suicide,

their reactions to the victim's family

were more negative. After a

tragedy,

an I-should-have-known-it-all- along phenomenon

can leave family, friends,

and therapists feeling

guilty.

David

Rosenhan (1973) and his

seven associates provided a

striking example of potential

error in

after-the-

fact explanations. To test

mental health workers'

clinical insights, they each

made an appointment

with

a different mental hospital

admissions office and complained of

"hearing voices." Apart from

giving

false

names and vocations, they

reported their life

histories and emotional states

honestly and exhibited

no

further

symptoms. Most were diagnosed as schizophrenic and

remained hospitalized for two to

three

weeks.

Hospital clinicians then

searched for early incidents

in the pseudo-patients' life histories

and

hospital

behavior that confirmed and

"explained" the diagnosis.

Rosenhan

later told some staff

members (who had heard about

his controversial experiment but

doubted

such

mistakes could occur in their

hospital) that during the

next three months one or more

pseudo-patients

would

seek admission to their hospital.

After the three months, he asked the

staff to guess which of the

193

patients

admitted during that time

pseudo-patients were really. Of the 193

new patients, 41 were accused by

at

least one staff member of

being pseudo-patients. Actually, there were

none!

Overconfidence

A

third problem with clinical

judgment is that people may

also supply information that

fulfills clinicians'

expectations.

In a clever series of experiments at the

University of Minnesota, Mark

Snyder (1984), in

collaboration

with William Swann and others, gave

interviewers some hypotheses to

test concerning

individuals'

traits. Snyder and Swann

found that people often

test for a trait by looking

for information that

confirms

it. If they are trying to

find out if someone is an

extravert, they often

solicit instances of

extraversion

("What would you do if you

wanted to liven things up at a

party?"). Testing for

introversion,

they

are more likely to ask,

"What factors make it difficult

for you to really open up to

people?"

Clinical

versus statistical prediction

Given

these hindsight- and diagnosis-confirming

tendencies, it will come as no surprise

that most clinicians

and

interviewers express more confidence in

their intuitive assessments

than in statistical data

(such as

using

past grades and aptitude

scores to predict success in graduate or

professional college). Yet

when re-

searchers

pit statistical prediction against

intuitive prediction, the statistics

usually win.

Statistical

predictions

are indeed unreliable, but

human intuition-- even expert

intuition--is even more

unreliable.

Three

decades after demonstrating the

superiority of statistical over

intuitive prediction, Paul

Meehl (1986)

found

the evidence stronger than ever.

190

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Social

cognition in problem

behaviors

Negative

cognitions can be related to

host of problems as mentioned

below:

·

Social

cognition and depression

·

Social

cognition and loneliness

·

Social

cognition and anxiety

·

Social

cognition and illness

Social

cognition and

depression

As

we all know from experience,

depressed people are

negative thinkers. They view

life through dark-

colored

glasses. With seriously

depressed people--those who

are feeling worthless, lethargic,

uninterested

in

friends and family, and unable to

sleep or eat normally--the

negative thinking becomes

self-defeating.

Their

intensely pessimistic outlook leads them

to magnify bad experiences and minimize

good ones.

·

Depressive

realism is the tendency of mildly

depressed people to make

accurate rather than

self-

serving

judgments, attributions, and

predictions.

·

In

over 100 studies involving

15,000 subjects, depressed

people have been more likely

than

nondepressed

people to exhibit a negative

explanatory style (Sweeney et al.

1986)

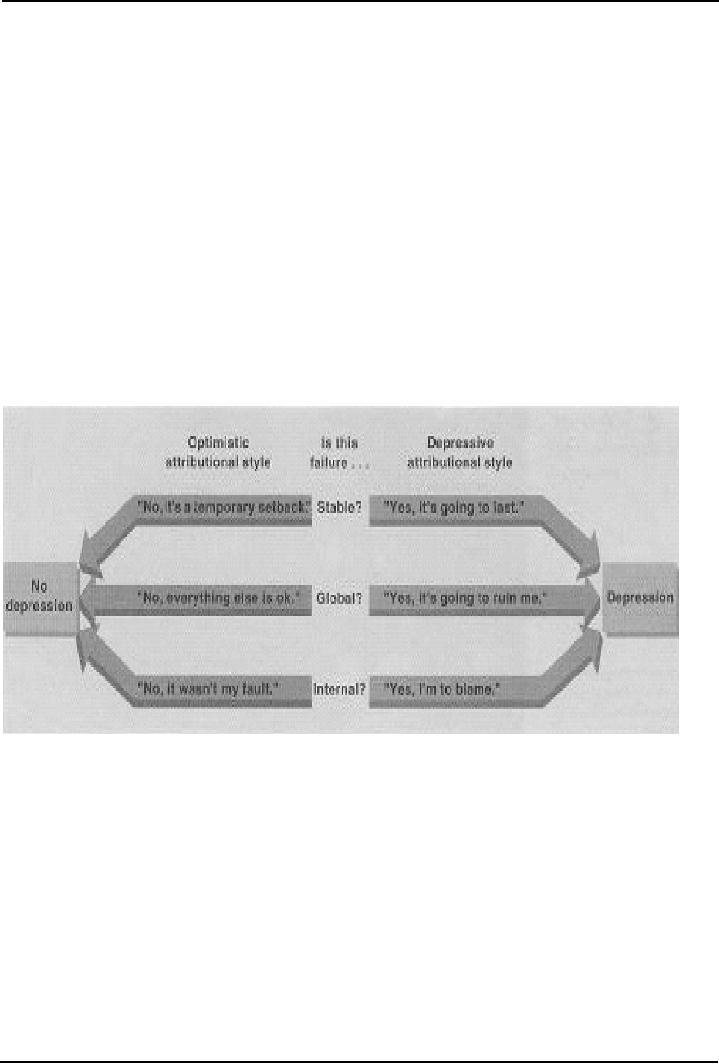

Figure

1: Depressive explanatory

style

Is

negative thinking a cause or a

result of depression?

Depressed

moods cause negative

thinking

·

Currently

depressed people recall

their parents as having been

rejecting and punitive. But

formerly

depressed

people recall their parents

in the same positive terms as do

never-depressed people

(Lewinsohn

& Rosenbaum, 1987).

·

Edward

Hirt and his colleagues (1992)

demonstrated, in a study of Indiana

University basketball

fans,

that even a temporary bad mood

induced by defeat can darken

our thinking. After the

fans

were

either depressed by watching

their team lose or elated by a

victory, the researchers

asked

them

to predict the team's future performance,

and their own. After a

loss, people offered

bleaker

assessments

not only of the team's

future but also of their

own likely performance at

throwing

darts,

and solving anagrams. When

things aren't going our way,

it may seem as though they

never

will.

·

Being

depressed has cognitive and

behavioral effects: A depressed mood

also affects behavior.

The

person

who is withdrawn, glum, and

complaining does not elicit

joy and warmth in others.

Stephen

191

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Strack

and James Coyne (1983) found

that depressed people were

realistic in thinking that

others

didn't

appreciate their behavior. Their

pessimism and bad moods

trigger social rejection.

Depressed

behavior

can also trigger reciprocal

depression in others. College students

who have depressed

roommates

tend to become a little

depressed themselves. In couples, too,

depression is often

contagious

(Katz & others, 1999).

Negative

thinking causes depressed

mood

·

Negative

explanatory style contributes to

depressive reactions.

·

One

study monitored university

students every six weeks

for two and a half

years (Alloy & others,

1999).

Only one percent of those who

began college with

optimistic thinking styles had a first

de-

pressive

episode, but 17 percent of those with

pessimistic thinking styles did.

·

"A

recipe for severe depression is

preexisting pessimism encountering

failure," notes

Martin

Seligman

(1991, p. 78). Patients who

end therapy no longer feeling

depressed but retaining

a

negative

explanatory style tend to

relapse as bad events occur (Seligman,

1992). If those with

a

more

optimistic explanatory style

relapse, they often recover

quickly

·

Vicious

cycle of depression makes one more

vulnerable to depression (see

below in Figure 2)

Figure

2: Vicious cycle of

depression

Social

cognition and

loneliness

If

depression is the common cold of

psychological

Depressed

SELF

disorders,

then loneliness is the headache.

Loneliness,

FOCUSED

Mood

whether

chronic or temporary, is a painful

awareness that

AND

SELF

BLAMED

our

social relationships are less

numerous or meaningful

than

we desire. Jenny de Jong-Gierveld (1987)

observed in

her

study of Dutch adults that

unmarried and unattached

people

are more likely to feel

lonely.

But

loneliness need not coincide

with aloneness. One

can

feel

lonely in the middle of a party and one

can be utterly

alone

in a room. Chronically lonely

people seem caught in

Cognitive

Negative

a

vicious cycle of self-defeating social

cognitions and

and

Experiences

Behavioral

social

behaviors. When paired with

a stranger of the same

Consequence

sex

or with a first-year college roommate,

lonely students

s

are

more likely to perceive the other

person negatively

(Wittenberg

& Reis, 1986).

Adolescents

experience such feelings more commonly

than do adults. When beeped by an

electronic pager

at

various times during a week and

asked to record what they were

doing and how they felt,

adolescents

more

often than adults reported

feeling lonely when alone

(Larsen & others, 1982). Males and

females feel

lonely

under somewhat different

circumstances--males when isolated from

group interaction,

females

when

deprived of close one-to-one

relationships (Berg & McQuinn). As

many recently widowed

people

know,

the loss of a person with

whom one has been attached

can produce unavoidable feelings

of

loneliness

(Stroebe & others, 1996).

Social

cognition and

anxiety

Shyness

is a form of social anxiety characterized by

self-consciousness and worry

about what others

think.

Compared

to unshy people, shy, self-conscious

people (whose numbers include

many adolescents) see

incidental

events as somehow relevant to

themselves. Shown someone

they think is interviewing them

live

(actually

a videotaped interviewer), they

perceive the interviewer as less

accepting and interested in them

(Pozo

& others, 1991).

Shy,

anxious people also

overpersonalize situations, a tendency

that breeds anxious concern

and, in

extreme

cases, paranoia. They also

overestimate the extent to which

other people are watching

and

192

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

evaluating

them. If their hair won't

comb right or they have a

facial blemish, they assume

everyone else

notices

and judges them accordingly. Moreover, shy

people often are conscious

of their self-consciousness.

They

wish they could stop

worrying about blushing,

about what others are

thinking, or about what to

say

next.

Social

cognition and

illness

·

Reactions

to illness

o

Noticing

symptoms

o

Explaining

symptoms: Am I sick?

o

Do I

need treatment?

o

Socially

constructed disorders (Small & others,

1991).

On

April 13, 1989, some

2,000 spectators assembled in an

Auditorium in

California,

USA, to enjoy music

performances by 600 secondary school

students.

Shortly

after the program began, the nervous

students began complaining to

one

another

of headaches, dizziness, stomachaches,

and nausea. Eventually

247

became

ill, forcing evacuation of the

auditorium. A fire department

treatment

operation

was set up on the lawn

outside. Later investigation

revealed nothing--no

diagnosable

illnesses and no environmental problems.

The symptoms subsided

quickly

and were not shared by the audience.

The instant epidemic, it

seemed, was

socially

constructed.

·

Emotions

and illness

·

Heart

disease has been linked

with a competitive, impatient,

and--the aspect that

matters--

anger-prone

personality (Matthews, 1988).

Under stress, reactive, anger-prone

"Type A"

people

secrete more of the stress hormones

believed to accelerate the buildup of

plaque on the

walls

of the heart's arteries.

·

Optimism

and health:

o

Link

between optimism & later good

health (Peterson et al.,

1988): In 1946

Harvard

University

students were assessed for

optimism, and in 1980 they were

reassessed. The

results

showed a link between early

optimism and later

health.

o

A

link between optimism and immunity to

common illnesses, like cold,

sore throat,

and

flu has been identified

(Scheier & Carver, 1991).

·

Stress

and illness

o

People

who undergo highly stressful

experiences become more vulnerable to

disease

The

death of a spouse, the stress of a space

flight landing, even the strain of an

exam week

o

have

all been associated with

depressed immune defenses (Jemmott &

Locke, 1984)

·

Explanatory

style and illness

o

As

defined earlier, negative

and pessimistic explanatory styles are

related with poor

outcomes

in mental and physical

health.

Social-psychological

approaches to treatment

Inducing

internal change through external

behavior

Consistent

with this attitudes-follow-behavior

principle, several psychotherapy techniques prescribe

action.

Behavior

therapists try to shape behavior and

assume that inner

dispositions will tag along

after the

behavior

changes. Assertiveness training employs

the foot-in-the-door procedure. The

individual first

role-

plays

assertiveness in a supportive context,

then gradually becomes

assertive in everyday life.

Rational-

emotive

therapy assumes that we

generate our own emotions;

clients receive "homework"

assignments to

talk

and act in new ways that

will generate new

emotions.

193

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Breaking

vicious cycles

If

depression, loneliness, and social

anxiety maintain themselves

through a vicious cycle of

negative

experiences,

negative thinking, and

self-defeating behavior, it should be

possible to break the cycle at

any

of

several points--by changing the

environment, by training the person to

behave more constructively, by

reversing

negative thinking. Several different

therapy methods help free

people from depression's

vicious

cycle.

Engaging

in Social skills training

Depression,

loneliness, and shyness are

not just problems in someone's

mind. To be around a

depressed

person

for any length of time

can be irritating and

depressing. As lonely and shy

people suspect, they

may

indeed

come across poorly in social

situations. In these cases,

social skills training may

help. By observing

and

then practicing new

behaviors in safe situations, the

person may develop the

confidence to behave

more

effectively in other

situations.

Explanatory

style therapy

The

vicious cycles that maintain

depression, loneliness, and shyness

can be broken by social skills

training,

by

positive experiences that

alter self-perceptions, and by changing

negative thought patterns. Some

people

have

social skills, but their

experiences with hypercritical

friends and family have convinced them

they do

not.

For such people it may be

enough to help them reverse

their negative beliefs about

themselves and

their

futures. Among the cognitive therapies

with this aim is an

explanatory style therapy proposed

by

social

psychologists.

One

such program taught

depressed college students to

change their typical

attributions. Mary

Anne

Layden

(1982) first explained the

advantages of making attributions more

like those of the

typical

nondepressed

person (by accepting credit

for successes and seeing how

circumstances can make things

go

wrong).

After assigning a variety of tasks,

she helped the students see

how they typically

interpreted

success

and failure. Then came the

treatment phase: Layden instructed

each person to keep a diary of

daily

successes

and failures, noting how

they contributed to their

own successes and noting

external reasons for

their

failures. When retested

after a month of this

attributional retraining and compared

with an untreated

control

group, their self-esteem had risen and

their attributional style had

become more positive. And

the

more

their explanatory style

improved, the more their depression

lifted. By changing their

attributions, they

had

changed their emotions.

Maintaining

change through internal

attributions for

success

·

Once

improvement is achieved, it endures

best if people attribute it to factors

under their own

control

rather than to a treatment

program.

·

More

recent focus less on the therapist

than on how the interaction affects the

client's thinking

(Neimeyer

et al., 1991)

·

The

thoughtful central route to

persuasion provides the most

enduring attitude and

behavior

change.

Social

support and well-being

There

is one other major topic in the

social psychology of mental and

physical well-being. Supportive

close

relationships--feeling

liked, affirmed, and encouraged by

intimate friends and

family--predict both

health

and

happiness. However, relationships

are associated with both

stress and happiness.

·

Our

relationships are fraught

with stress.

·

"Hell

is others," wrote Jean-Paul

Sartre

·

Still,

on balance, close relationships

contribute less to illness

than to health and

happiness.

194

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Close

relationships and health

·

Those

who have close relationships

with friends, kin, or other

members of close-knit religious

or

community

organizations are less

likely to die prematurely.

And losing such ties heightens the

risk

of

disease.

·

A

Finnish study of 96,000

widowed people found their

risk of death doubled in the week

following

their

partner's death (Kaprio & others,

1987).

·

A

National Academy of Sciences

study reveals that those who

are recently widowed become

more

vulnerable

to disease and death (Dohrenwend &

others, 1982).

·

Among

the elderly, those having

long-term close relationships

with less than three people

were

much

more likely to die in the next three

years (Cerhan & Wallace,

1997).

·

In

more than 80 studies, social support has

been linked with better

functioning cardiovascular and

immune

systems (Uchino & others,

1996).

Close

relationships and happiness

·

Friendships and

happiness

o

Being

attached to friends with

whom we can share intimate

thoughts has two effects,

"It

redoubleth

joys, and cutteth griefs in

half" (Francis Bacon).

·

Marital

attachment and happiness

o

Compared to

those single or widowed, and

especially compared to those

divorced or

separated,

married people report being

happier and more satisfied with

life (Inglehart,

1990)

·

The

tighter social bonds of collectivist

cultures offer protection from

loneliness, alienation,

divorce,

and

stress-related diseases.

Readings:

·

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002). Social

Psychology (7th ed.). New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Taylor,

S.E. (2006). Social

Psychology (12th ed.). New York: Prentice

Hall.

·

195

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition