|

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

38

PROSOCIAL

BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE.........)

Aims

To

introduce psychological aspects of

prosocial behaviour

Objectives

·

Discuss

different explanations of helping

behavior: Why do we

help?

·

Evaluate

the Bystander Intervention

Model

·

Discuss

two psychological processes

that can prevent

helping

·

Describe

Emotional arousal & Cost-Reward Assessments in the

process of

prosocial

behavior

·

Describe

the individual variables affecting

prosocial behavior: Who

helps?

Bystander

Intervention

Two

psychological processes can prevent

helping at different

stages

·

The

audience inhibition effect (stage

1)

·

Diffusion

of responsibility (stage 2)

The

audience inhibition

effect

People

are inhibited from helping

for fear of negative

evaluation by others if they

intervene and the

situation

is not an emergency

Latane

& Darley (1968)

·

Recruited

male college students for a

study on problems of urban

life

·

Hypothesized

that when others are

present, people are less

likely to perceive a

potentially

dangerous

situation as an emergency, especially

when others seem

unconcerned.

·

Participants

sitting in a room completing a

questionnaire

·

Three

experimental conditions: participant

alone, with 3 other

participants or with 2 unconcerned

confederates

·

White

smoke starts entering the

room through a small air

vent

·

After

6 minutes too thick to see

through!

·

What

would the participant do

Alone

in

different situations?

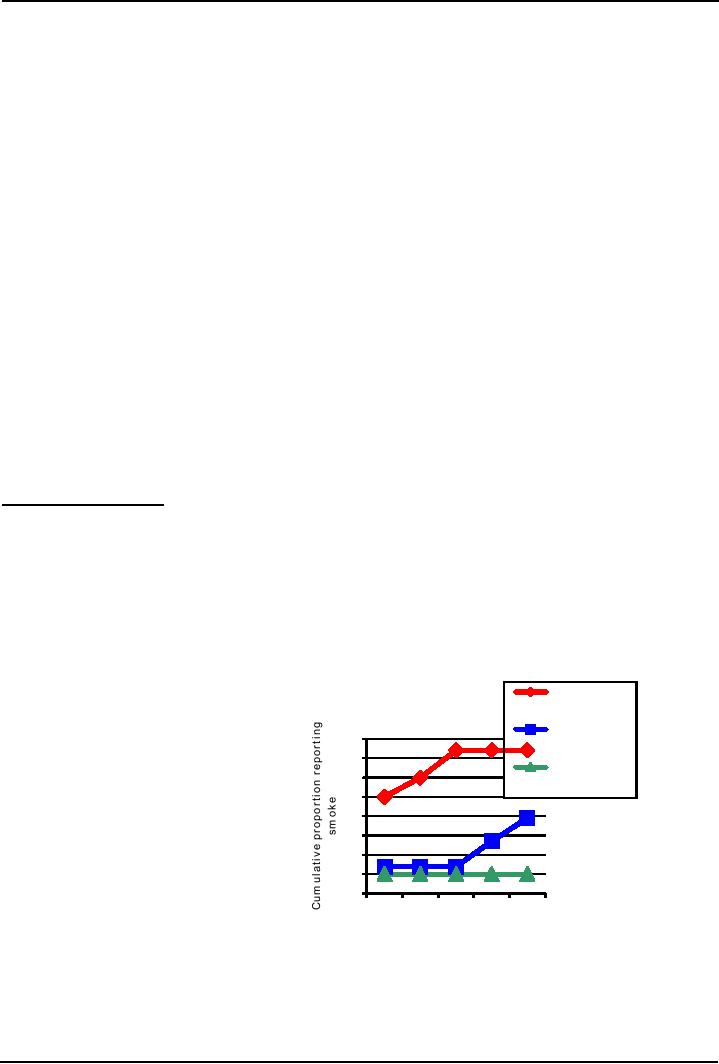

Audience

inhibition

3

naive

The

results are illustrated in Figure

1:

80

participants

70

2

passive

The

graph above shows that when

alone

60

confederates

75%

of the time the participant

finally

50

left

the room to report the emergency.

40

However,

when the participant

was

30

others

in only 38% of the trials,

did a

20

single

person report the incident

before

10

the

six-minute mark. As opposed

to

0

these

two conditions, when others

were

2

3

4

5

6

calm

more audience inhibition effect

Time

from smoke infusion

(minutes)

occurred.

The researchers concluded

that

when others are present,

people:

·

not

only are less likely to

define

a

potentially dangerous situation as

emergency

·

respond

more slowly

157

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Another

study was conducted to investigate the

audience inhibition effect.

Latane

& Rodin (1969)

·

Experimenter

leaves participant in a

room

·

After

several minutes a tape is played in which

a crashing sound is heard and then

the

experimenter's

screaming...

·

"Oh my

God, my foot...I ..I..can't

move...it..... Oh . my ankle...I...can't get

this...thing...off me...."

·

70%

helped when alone, only 7%

helped with unconcerned

confederates!

Explanations

of audience inhibition

·

Evidence

comes from conformity

research (experiments of Sherif

and Asch).

·

Information

influence (looking to others to

define uncertain situations):

When we are not clear

how

to

define a particular situation, we

are likely to become dependent on

others for a definition

of

social

reality. Thus when a group of

people witnesses a possible emergency,

each person bases

his

interpretation

of the event partly or exclusively on the

reaction of others. In "Smoke" and

"Woman

in

distress" studies, others' behavior

significantly inhibited

helping.

·

Normative

influence (fear of being

negatively evaluated - `losing

your cool'). People have learned

to

maintain a calm "exterior" so that

other people do not evaluate

us negatively.

·

Postexperimental

debriefing with the participants

indicated that some

participants who did

not

intervene

claimed that they were

either unsure of what had occurred or

did not think that

the

situation

was very serious.

Diffusion

of responsibility

In

some situations there is a clear emergency

(not ambiguous and no fear of `getting it

wrong'). When

others

are present people believe

they are less personally

responsible.

Darley

and Latane believed that

this realization that others

could also help diffused the

neighbours' own

feelings

of individual responsibility. They

called this response to

others' presence the

diffusion

of

responsibility--the

belief that the presence of

other people in a situation

makes one less

personally

responsible

for events that occur in

that situation.

Experiment

of Darley & Latane

(1968)

·

In

this study, participants

(New York University

students) thought that they

were participating in a

discussion

about the kinds of personal problems undergraduates

typically face in a large

urban

environment.

·

They

were also told that to avoid

embarrassment, they each

would be placed in separate booths

and

would

talk to one another using an intercom

system. The way the intercom

system worked was

that

only

one person could speak at a

time, and the others had to

merely listen.

·

Experimenter

said would not be listening

in on intercom

·

The

study included three different

conditions. Some participants were

told the discussion would

be

with

just one other student,

while others were told they

were either part of a three-person or a

six-

person

group.

·

Discussion

began with the first speaker

stating that he was an

epileptic who was prone to

seizures

when

studying hard or when taking

exams. When everyone else

had spoken, the first speaker

began

to

talk again, but now he

was speaking in a loud and

increasingly incoherent

voice.

·

All

other discussants were tape

recordings.

·

The

percentage of helping decreased as

the number of strangers present

increased.

·

In

many replications when alone

75% helped vs. 53%

when with others.

·

People

deny that the presence of

others affected their

inclination to help.

158

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

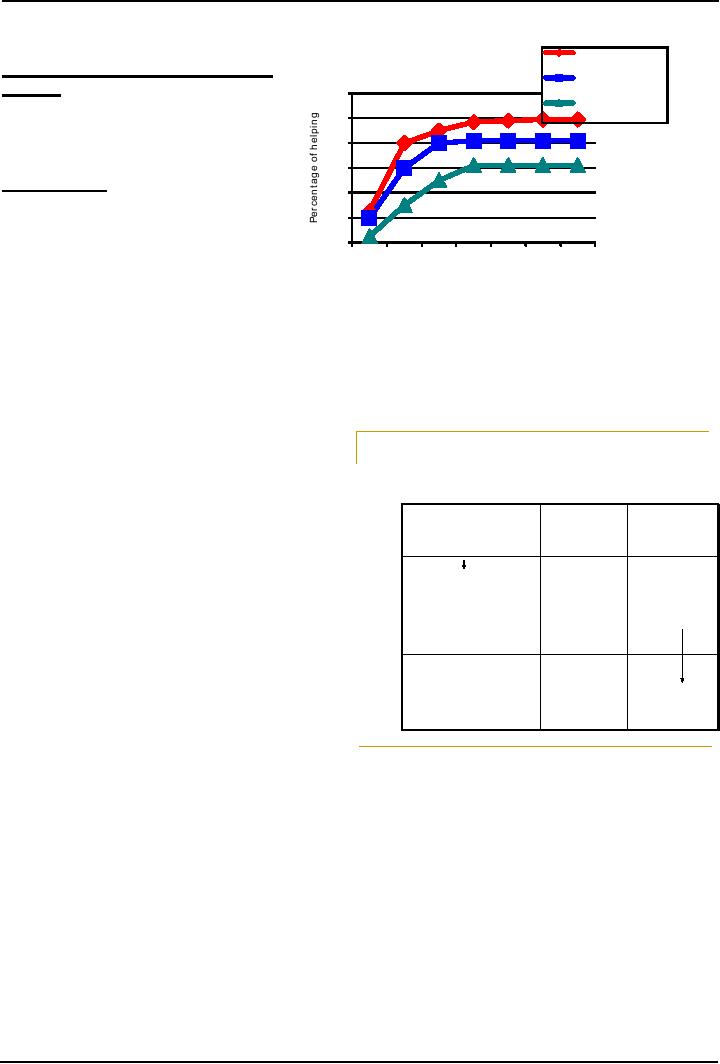

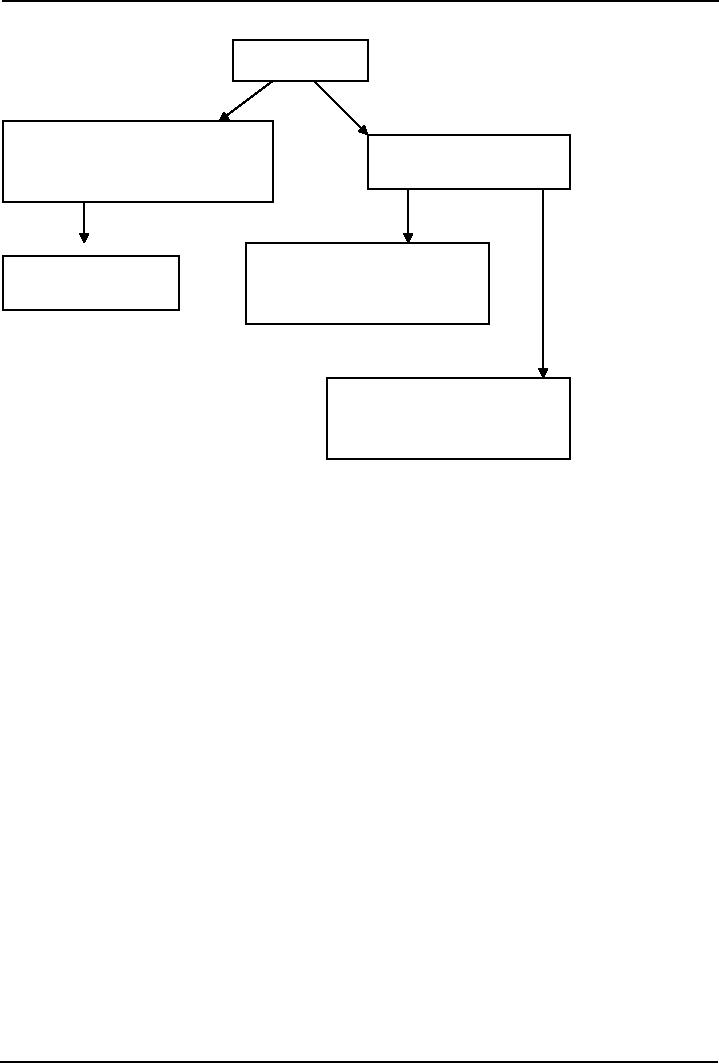

The

experiment described above is illustrated

in Figure 2:

Participant

alone

Diffusion

of responsibility

Diffusion

of responsibility on the

Participant

with a

Internet

stranger

120

·

Diffusion

of responsibility also

Participant

with four

strangers

100

occurs

when people need

help

on

the Internet

80

60

Markey

(2000):

40

·

More

than 4,800 people

were

20

monitored

in 400 different

Internet

chat groups over a

0

month's

time to determine the

40

80

120

160

200

240

280

Seconds

from beginning of

fit

amount

of time it took to render

assistance

to someone who

asked

for help.

·

It

took longer for people to

receive help as the number of

people present in a

computer-mediated

chat

group increased.

·

However,

this diffusion of responsibility

was virtually eliminated and

help was received

more

quickly

when help was asked

for by specifying a bystander's

name.

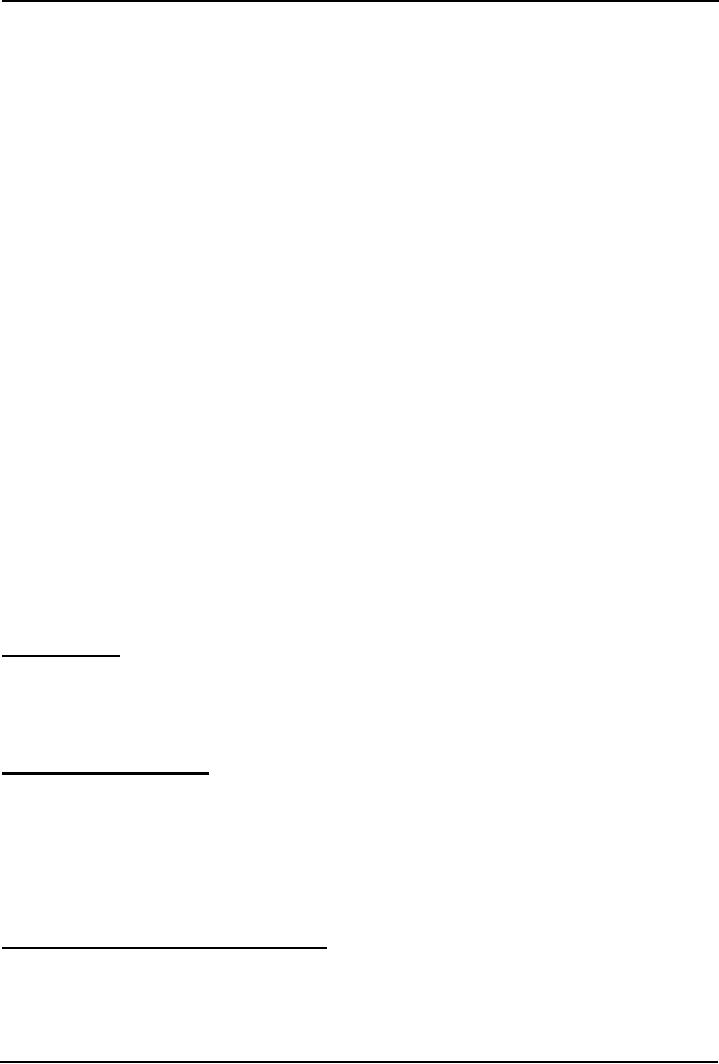

Emotional

arousal

&

Cost-Reward

Emotional

Arousal and Cost-Reward

Assessments

assessments

Piliavin et al.

(1981)

(

Piliavin et al. (1981)

)

Latane

and Darley explain the social

problem of

non-intervention;

Piliavin describes why

we

Cost

for direct help

Low

High

decide

to help in emergency. Jane Piliavin

and

Cost

for no help

her

colleagues (1981) attempted to answer

this

question

by developing a theory of

bystander

High

Direct

Indirect

intervention

that extends and complements

intervention

intervention

Latane

and Darley's model. These

researchers

OR

added

to the decision-making equation by

Redefinition

focusing

on bystanders' emotional arousal

of

situation

during

an emergency and their assessment of

the

Low

Variable:

Leaving

the

costs

of helping and not helping.

Essentially,

perceived

scene

their

work focuses on the later

part of Latane

norm

ignoring,

and

Darley's model, namely,

deciding on

denial

personal

responsibility (step 2),

deciding what to

do

(step 3), and implementing

action (step 4).

According

to their arousal

cost-reward model of helping,

witnessing an emergency is

emotionally

arousing

and is generally experienced as an uncomfortable

tension that we, as

bystanders, seek to

decrease.

This

tension can be reduced in several

different ways. We could intervene

and thereby decrease

our

arousal,

but we could also reduce

arousal by either ignoring danger signs

or benignly interpreting them as

nothing

to worry about.

What

are the costs to the bystander for

helping? This could involve

a host of expenditures, including

loss of

time,

energy, resources, health

(even life), as well as the

risk of social disapproval and

embarrassment if the

help

is not needed or is ineffective. If

both types of costs are low,

intervention will depend on the

perceived

social

norms in the situation. The

most difficult situation for

bystanders is one in which the

costs for

helping

and for not helping are

both high. Here, the arousal cost-reward

model suggests two likely

courses

of

action:

159

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

1.

One is for bystanders to

intervene indirectly by calling the

police, an ambulance, or some

other

professional

helping source.

2.

Another course of action is

for bystanders to redefine the

situation in a way that

results in them not

helping.

Here, they could decide there

really is no emergency after all, or

that someone else

will

help,

or that the victim deserves to

suffer.

This

theory's consideration of these two

cost factors cannot explain the behavior

of heroes, but it

does

explain

the behavior of more ordinary bystanders

in emergency situations. However, a number of

studies

support

the arousal cost-reward model's hypothesis that people

often weigh the costs of

helping and not

helping

prior to rendering

assistance.

Who

Helps?

Positive

and negative

moods

·

Alice

Isen (1970) administered a series of

tests to college students

and teachers

·

Three

experimental and one control condition:

In experimental conditions, participants

were later

told

that they had either

performed very well or very

poorly. The third group

was told nothing at

all

about

their performance. In addition to these

three experimental conditions, a control

group was not

administered

any tests at all.

·

The

participants who had "succeeded" at the

tests were later more likely to

help a woman

struggling

with an armful of books than

any of the other

participants.

·

This

good

mood effect following

success has been replicated

in other studies (Klein,

2003)

·

People

in good mood are more likely

to help due to following

reasons:

·

Perceive

other people as "nice,"

"honest," and "decent," and

thus deserving of our

help.

·

We

help others to enhance or

prolong our good

mood.

·

When

happy, we are less likely to

be absorbed in our own

thoughts; thus, we are more

attentive

to

others' needs.

·

A

fourth possibility is that

good moods increase the

likelihood that we think

about the

rewarding

nature of social activities in general.

Other

Research:

People

are more likely to help

others:

·

on

sunny days than on cloudy

ones (Cunmngham, 1979)

·

after

finding money or being

offered a tasty treat (Isen & Levin,

1972)

·

after

listening to uplifting music or

seeing a comedy (North et al.,

2004; Wilson, 1981).

Bad

moods and seeking

relief

·

Isen

and her coworkers (1973) found that

people who believed they had

failed at an experimental

task

were more likely to help another person

than those who did

not experience failure.

·

Although

this response certainly

seems to contradict the good

mood effect just described,

one

possible

link between the two moods is the

rewarding properties of

helping.

·

Negative

moods sometimes

lead

to more helping because helping

others often makes us feel

good

about

ourselves, when feeling bad we

may help as a way of

escaping our mood--just as we

help

when

we are in a good mood to

maintain that mood.

Michael

Cunningham and his colleagues

(1980):

·

Feeling

guilty can also increase

helping behavior. Michael

Cunningham and his colleagues

(1980)

conducted

a field study in which

individuals were approached on the street

by a young man who

asked

people to use his camera to

take his picture for a

class project.

160

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

·

The

problem for the would-be helpers

was that the camera had

been rigged to malfunction.

When

the

helpers realized the camera was

not working, the young man

examined camera closely

and

asked

the helpers if they touched any of the

dials.

·

He

then informed them that it

would have to be repaired. The

researchers assumed that

such an

encounter

would induce a certain

degree of guilt in these

individuals.

·

These

now guilty people passed a

young woman who suddenly

dropped a file folder

containing

some

papers.

·

How

do you think they responded

to this needy

situation?

·

Only

40% of the passersby who had

no broken camera experience paused to

help; in comparison

80%

of guilty helped.

Debate

over the effect of negative

mood on prosocial behavior

Although

these studies demonstrate

that negative moods can

also lead to prosocial

behavior, Robert

Cialdini

and Douglas Kenrick (1976) attempted to

explain why this is the case

by proposing that when

we

are

in a bad mood, our decision to

help is often based on a

simple self-serving question:

Will helping make

us

feel better? For those in a bad

mood, helping when we are in

a bad mood, if the perceived benefits

for

helping

are high and the costs

are low, the expected reward

value for helping will be

high, and thus, we will

likely

help to lift our own

spirits. However, if the perceived

benefits and costs are

reversed so that the

reward

value is low, we are

unlikely to help. Essentially,

this model predicts that bad

moods are more likely

to

lead to helping than neutral

moods when helping is easy

and highly rewarding. Studies suggest

that when

we

experience extremely negative moods,

such as grief or depression, we

may be so focused on our

own

emotional

state that we simply don't

notice others' needs and

concerns (Carlson & Miller,

1987). Other

studies

suggest that even when

experiencing less severe

negative moods, we are less

likely to help than

those

who are in good moods

(Isen, 1984). The "negative

state relief model" answers

this debate by

asserting

that perceived benefits for

helping determine whether bad

mood will lead to help or

not (Cialdini

&

Kenrick, 1976).

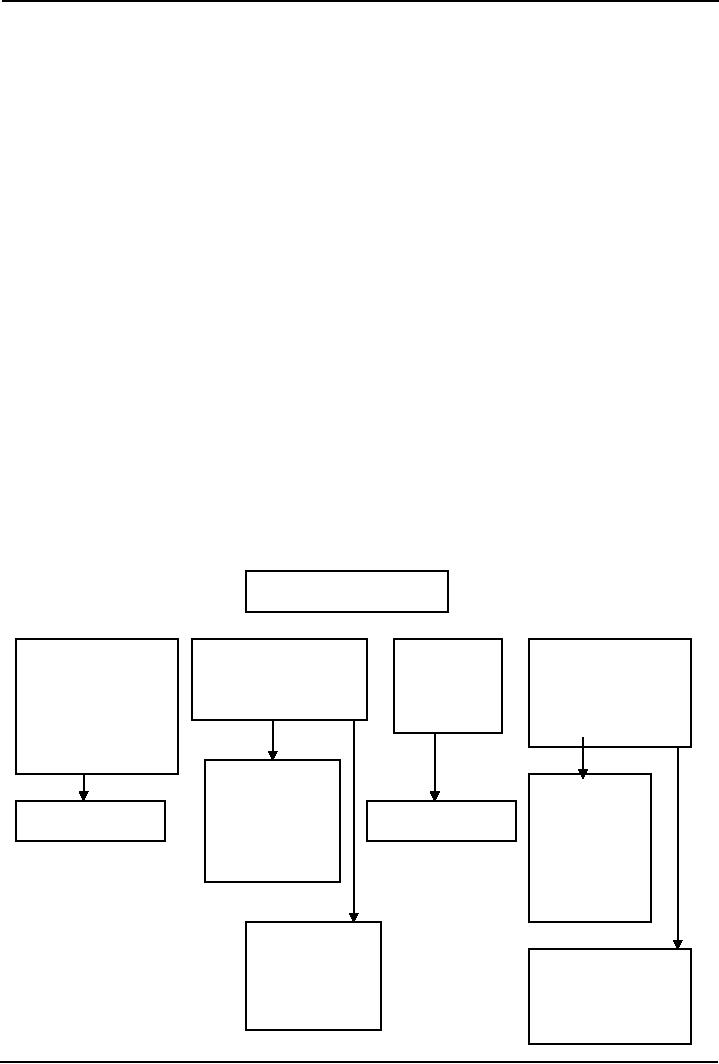

The

varied effects of mood on

helping:

Good

mood

Greater

attention

Desire

to prolong

More

More

likely to

to

social

good

mood

likely

to

think

about the

environment

perceive

rewarding

nature

increases

likelihood

people

in a

of

social activities

of

noticing other's

needs

More

helping

More

if

help is

helping

if

More

helping

More

helping

expected

to

help

is

maintain

expected

to

mood

bring

rewards

Less

helping if

help

is

Less

helping if

expected

to

help

is not

destroy

mood

expected

to bring

rewards

161

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Bad

mood

Self

focused attention

reduces

Desire

to improve

likelihood

of noticing other's

mood

needs

More

helping unless costs

Less

helping

are

believed to out weigh

rewards

Less

helping if mood is

elevated

by some other

sources

Reading

·

Franzoi,

S. (2003). Social

Psychology. Boston:

McGraw-Hill. Chapter 14.

Other

Readings

·

Lord,

C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace and Company. Chapter

8.

·

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002). Social

Psychology (7th ed.).

New York:

McGraw-Hill.

·

Taylor,

S.E. (2006). Social

Psychology (12th ed.). New York: Prentice

Hall.

162

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition