|

LEADERS IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING FOR QUALITY:User-Based |

| << TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING FOR QUALITY AT OFFICE |

| TAGUCHI LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT >> |

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

Lesson

# 07

LEADERS

IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING

FOR QUALITY

The

Concept AND Definition of

Quality

While

managers have shown interest in the concept of

quality, many have been

frustrated by its

elusiveness.

They find diverse and

often conflicting definitions in

professional books, journals,

and

news

media. Despite common themes such as

continuous improvement, customer focus,

and excellence,

different

people emphasize different

things. For example, in a

1991 public television special,

"Quality

or

Else," executives, managers, workers,

academics, and others defined

quality variously as

follows:

·

A

pragmatics system of continual

improvement, a way to successfully

organize man and

machines.

·

The

meaning of excellence

·

The

unyielding and continuing effort by

everyone in an organization to understand,

meet, and

exceed

the needs of its

customers

·

The

best product that you

can produce with the materials

that you have to work

with

·

Continuous

good product which a

customer can trust.

·

Producing

a product or service that meets the

needs or expectations of the

customers.

·

Not

only satisfying customers,

but delighting them, innovating,

creating.

Your

own sample of definitions

would probably reveal

similar variety. Different

companies, and

different

people within the same

company, often disagree on the

definition of quality. Sometimes

the

disagreement

is merely due to semantics.

Sometimes they are the

result of focusing on

different

dimensions

of quality. Other times the differences

are more profound, implying

conflicting courses of

action

and approaches to management. Here we

look at several views of quality and

then offer a

definition

that should help to

integrate managerial efforts to

improve quality throughout an

organization.

The

Transcendent View of Quality

The

concept of quality has often

been defined, from a

transcendent view, as "innate

excellence". This

view

implies that high quality is

something timeless and enduring, an

essence that transcends or

rises

above

individual tastes or styles. It often

regards quality as an un-analyzable

property that people

learn

to

recognize through experience, just as

Plato argued that beauty can

be understood only after exposure

to

a series of objects that display

its characteristics.

A

Critique of the Transcendent View of

Quality

Walter

A. Shewhart, the father of modern-day

statistical quality control,

offered the following

criticism

of

the transcendent view of

quality:

Dating

at least from the time of

Aristotle, there has been

some tendency to conceive of quality

as

indicating

the goodness of an object. The

majority of advertisers appeal t the public

upon the basis of

the

quality of product. In so doing,

they implicitly assume that

there is a measure of goodness which

can

be

applied to all kinds of

product, whether it be vacuum tubes,

sewing machines

automobiles.

The

transcendent view of quality

essentially tells a manager

"you will know it when

you see it" and

does

not inform managers how to

pursue excellence. Certainly the notion

of excellence is an important

and

inspirational component of quality.

However, future managers

must have a better understanding

of

the

concept. The definition of quality

must be more pragmatic, more objective,

and more tangible. It

must

inform managers about how to

make improvements.

To

better understand how this

total views of quality

impacts managerial practices, it is

useful to

understand

how managerial approaches to

quality have evolved from a

narrow view, focused

on

26

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

inspection

and conformance to specified standards,

toward a broader view, focused on

organizational

strategy

for providing superior

customer value. We now

discuss the evolution of quality

approaches.

Product-Based

Shewhart

explains that the word

"quality," in Latin, qualities,

comes from quails, meaning

"How

constituted"

and signifies a thing's basic nature.

Emphasizing a product-based view of

quality, Shewhart

argued

that the quality of a manufactured

product may be described in

terms of a set of

characteristics.

Product-based

definitions of quality suit engineers

because they are concerned

with translating

product

requirements

into specific components and

physical dimensions that can be produced.

For example,

measurement

of capacity, inductance, and resistance

may be used to define the

quality of a relay.

So,

according

to this view, quality is a

precise and measurable

variable: differences in quality

reflect

differences

in the quantity of an attribute the

product possess (Garvin,

1988). For example,

high-quality

rugs

have a large number of knots per square

inch. Quality in a rug can

be seen as an inherent

characteristic

that can be assessed

objectively. Since quality reflects the

quantity of attributes

contained

by

a product, and because

attributes are costly to produce,

high quality means higher

cost. In this view, a

Cadillac

loaded with a number of amenities is a

higher-quality car than a

stripped-down Chevrolet.

The

product-based view has some

merit, but it does not

accommodate differences in individual

tastes

and

preferences.

Manufacturing-Based

Another

meaning of the word "quality" is

"the degree of excellence that a

thing possess" once it

is

manufactured.

The manufacturing-based view of quality

focuses on manufacturing and

engineering

practices,

emphasizes conformance to specified requirements,

and relies on statistical analysis

to

measure

quality. As you will see, it

contradicts the notion that higher

quality necessarily corresponds to

higher

cost. Returning to the example of a

relay, Shewhart suggests the overall

quality of a relay can

be

further

expressed in terms of whether it

meets engineering specifications

for product-based

characteristics

(qualities), such as capacity,

inductance, and resistance. To simplify,

let's just consider

two

dimensions, resistance and inductance.

The

quality or degree of excellence of a

product (represented by a point or a

set of two

measurements)

falling

within the rectangular region

would be characterized as good or

satisfactory. A product

with

quality

outside the region, not

conforming to satisfactions, would be characterized as

bad or

unsatisfactory.

Of course, real manufacturing

processes produce a stream of products.

Ideally, each

individual

product has quality that

conforms to specification. However,

variation in the production

process

may produce some products that

are outside the

specifications.

Shewhart

suggested that the fraction

of nonconforming items produced by a manufacturing

process can

be

studied statistically to assess

quality. The knowledge

gained from statistical

studies can be used

to

improve

the control of quality, thus

ensuring that a larger

fraction of the products conform

to

specification.

By stabilizing and reducing variation in

the process, managers can

ensure that product

quality

is always within specification.

Such improvement would mean

fewer defects, les scrap,

less

rework,

and consequently, less

cost.

User-Based

The

user-based perspective does not abandon

manufacturing quality as a strategic

objective, but

provides

a context for it. As Shewhart

says, "The broader concept of economic

control naturally

includes

the problem of continually shifting the

standards expressed in terms of

measurable physical

properties

to meet best the shifting economic

value of these particular

physical characteristics

depending

upon

shifting human wants". The

user-based

view of quality, popular

with people in

marketing,

presumes

that quality rests in "the

eye o the beholder," the user of the

product, rather than an

engineer's

specified

standards.

27

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

The

Concept of Customer Value

Value-based

approaches expand on the user-based

view f quality by incorporating the

notion of "price

of

costs." Regarding value-based approaches,

Garvin (1988) suggests "a

quality product is one

that

provides

performance or conformance at an acceptable price or

cost. By this reasoning, a $ 500

running

shoe,

no matter how well-constructed, could

not be a quality product,

for it would find few

buyers." In

support

of this view, researchers have

demonstrated a positive relationship

between market share

and

value-based

measures of quality. Other

examples contradict this value-based

approach which assumes

that

lower cost always means

higher value to the customer. Designer

dresses that sell for

$5,000, or

luxury

cars that cost more than a

home, suggest that there is another

dimension of value. The

definition

of

customer value offered below

expands on this value-based definition of

quality. In fact, the

customer

value

concept encompasses all of the

foregoing definitions of

quality.

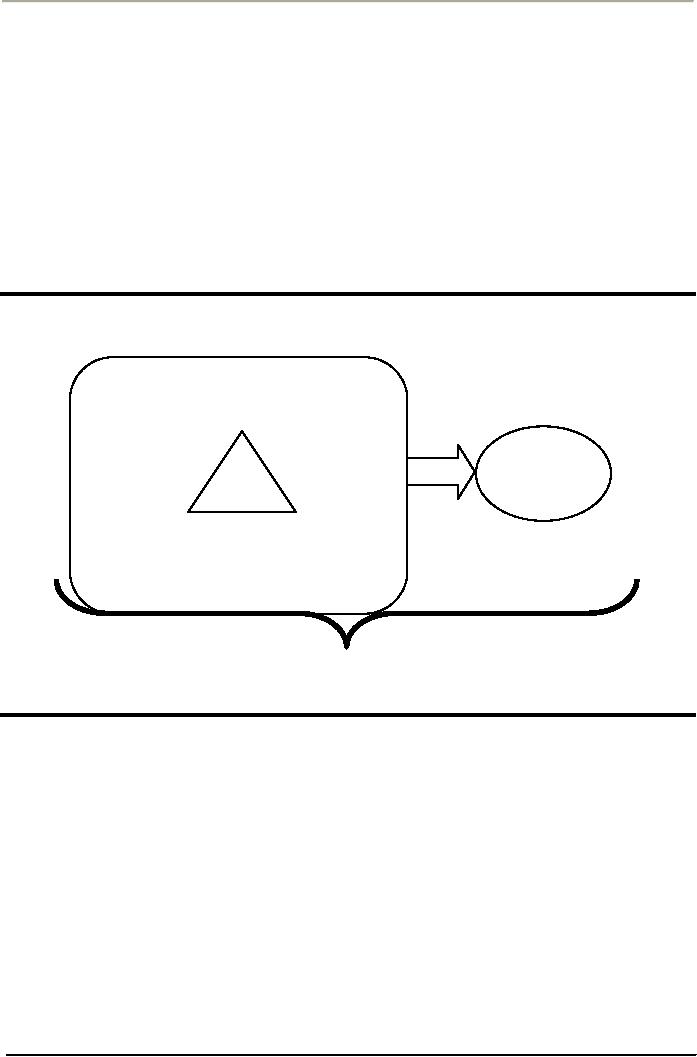

Quality

improvement for customer

value

Customer

Quality

of

Quality

of

Purpose:

design/redesign

performance

customer

value

Quality

of

Design

Product

conformance

Apply

Quality improvement

Process

throughout

We

define customer value as a

combination of benefits and sacrifices

occurring when a customer

uses a

product

or service to meet certain needs.

Those consequences that

contribute to meeting one's

needs are

benefits,

while those consequences

that detract from meeting

one's needs are

sacrifices.

For

example, a person who

purchases a large luxury car

to satisfy a need for pleasurable

travel might

enjoy

such benefits as comfort,

restfulness, and audio entertainment. On

the other hand, the person

also

has

to make certain sacrifices, such as

paying for the vehicle,

difficulties in parking a large

vehicle, and

fuel

and maintenance costs these sacrifices

detract from meeting customer

needs. For example, if the

car

owner

lives in a town that doesn't

have a dealership for the luxury car, he or

she will incur costs

such as

frustration,

time, and the inconvenience of going to

another town for service.

The

concept of customer value

encompasses the benefits and sacrifices

associated with the customer's

use

process throughout the life

cycle of product ownership. As

Deming (1986) suggests:

"Quality must

be

measured by the interaction between three

participants: "Quality must be

measured by the interaction

between

three participants: (1) the product

itself; (2) the user and

how he uses the product, how

he

28

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

installs

it, how he takes care of

it; and (3) instructions for

use, training of customer and

training of

repairman,

service provided for repairs, and

availability of parts."

The

concept of customer value

also encompasses all the

definitions of quality mentioned so

far. To

provide

value to customers, managers

must ensure the

following:

1.

Quality

of Design/Redesign

Product

designs conform to customer

needs (product-based and user-based

quality). For

example,

automobile producers design car

seat to conform to the contours of the

diver's back.

2.

Quality

of Conformance:

Product

manufactured conforms to product designs

(manufacturing-based quality). For

example,

each car seat produced meets

the targeted design

specifications.

3.

Quality

of Performance:

Products

manufactured conform to customer needs by

performing in the field

(user-based

quality).

For example, the car seats

maintain their shape after

years of use.

All

of these dimensions of quality should be

managed through a quality

improvement process

that

enhances

customer value. Placing

quality in the broader context of

customer value counteracts

the

tendency

of people with different

functional orientations within an

organization t take different

views of

quality

(Garvin, 1988). For example,

marketing people tend to have a

user-based and product-based

view

that focuses on matching

product characteristics with

customer perceptions. Engineers, on the

other

hand, tend to take a product-based view

that focuses on defining

product characteristics.

Manufacturing

people tend to view quality

as conformance to specification and

targets.

29

Table of Contents:

- OVERVIEW OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT:PROFESSIONAL MANAGERIAL ERA (1950)

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND TOTAL ORGANIZATION EXCELLENCE:Measurement

- INTEGRATING PEOPLE AND PERFORMANCE THROUGH QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- FUNDAMENTALS OF TOTAL QUALITY AND RATERS VIEW:The Concept of Quality

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND GLOBAL COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE:Customer Focus

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING FOR QUALITY AT OFFICE

- LEADERS IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING FOR QUALITY:User-Based

- TAGUCHI LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- WTO, SHIFTING FOCUS OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL OF MANAGEMENT

- HISTORY OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT PARADIGMS

- DEFINING QUALITY, QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND LINKS WITH PROFITABILITY

- LEARNING ABOUT QUALITY AND APPROACHES FROM QUALITY PHILOSOPHIES

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT THEORIES EDWARD DEMING’S SYSTEM OF PROFOUND KNOWLEDGE

- DEMING’S PHILOSOPHY AND 14 POINTS FOR MANAGEMENT:The cost of quality

- DEMING CYCLE AND QUALITY TRILOGY:Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress

- JURAN AND CROSBY ON QUALITY AND QUALITY IS FREE:Quality Planning

- CROSBY’S CONCEPT OF COST OF QUALITY:Cost of Quality Attitude

- COSTS OF QUALITY AND RETURN ON QUALITY:Total Quality Costs

- OVERVIEW OF TOTAL QUALITY APPROACHES:The Future of Quality Management

- BUSINESS EXCELLENCE MODELS:Excellence in all functions

- DESIGNING ORGANIZATIONS FOR QUALITY:Customer focus, Leadership

- DEVELOPING ISO QMS FOR CERTIFICATION:Process approach

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY:Issues to be Considered

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 6) RESOURCES MANAGEMENT:Training and Awareness

- ISO 9001(2000) (CLAUSE # 7) PRODUCT REALIZATION AND CUSTOMER RELATED PROCESSES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 7) CONTROL OF PRODUCTION AND SERVICES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 8) MEASUREMENT, ANALYSIS, AND IMPROVEMENT

- QUALITY IN SOFTWARE SECTOR AND MATURITY LEVELS:Structure of CMM

- INSTALLING AN ISO -9001 QM SYSTEM:Implementation, Audit and Registration

- CREATING BUSINESS EXCELLENCE:Elements of a Total Quality Culture

- CREATING QUALITY AT STRATEGIC, TACTICAL AND OPERATIONAL LEVEL

- BIG Q AND SMALL q LEADERSHIP FOR QUALITY:The roles of a Quality Leader

- STRATEGIC PLANNING FOR QUALITY AND ADVANCED QUALITY MANAGEMENT TOOLS

- HOSHIN KANRI AND STRATEGIC POLICY DEPLOYMENT:Senior Management

- QUALITY FUNCTION DEPLOYMENT (QFD) AND OTHER TOOLS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

- BASIC SQC IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:TOTAL QUALITY TOOLS DEFINED

- HOW QUALITY IS IMPLEMENTED? A DIALOGUE WITH A QUALITY MANAGER!

- CAUSE AND EFFECT DIAGRAM AND OTHER TOOLS OF QUALITY:Control Charts

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL (SPC) FOR CONTINUAL QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL….CONTD:Control Charts

- BUILDING QUALITY THROUGH SPC:Types of Data, Defining Process Capability

- AN INTERVIEW SESSION WITH OFFICERS OF A CMMI LEVEL 5 QUALITY IT PAKISTANI COMPANY

- TEAMWORK CULTURE FOR TQM:Steering Committees, Natural Work Teams

- UNDERSTANDING EMPOWERMENT FOR TQ AND CUSTOMER-SUPPLIER RELATIONSHIP

- CSR, INNOVATION, KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INTRODUCING LEARNING ORGANIZATION