|

Describing Risk:Unequal Probability Outcomes |

| << The Aggregate Demand For Wheat:NETWORK EXTERNALITIES |

| PREFERENCES TOWARD RISK:Risk Premium, Indifference Curve >> |

Microeconomics

ECO402

VU

Lesson

13

Introduction

Choice

with certainty is reasonably

straightforward.

How

do we choose when certain

variables such as income and

prices are uncertain

(i.e.

making

choices with risk)?

Describing

Risk

To

measure risk we must

know:

1)

All of the possible

outcomes.

2)

The likelihood that each

outcome will occur (its

probability).

Interpreting

Probability

The likelihood

that a given outcome will

occur

Objective

Interpretation

∑

Based on the

observed frequency of past

events

Subjective

∑

Based on

perception or experience with or

without an observed

frequency

Different

information or different abilities to

process the same information

can

influence

the subjective

probability

Expected

Value

The weighted

average of the payoffs or

values resulting from all

possible outcomes.

∑

The

probabilities of each outcome

are used as weights

∑

Expected value

measures the central

tendency; the payoff or

value expected on

average

An

Example

∑

Investment in

drilling exploration:

∑

Two outcomes

are possible

Success --

the stock price increase

from $30 to $40/share

Failure --

the stock price falls

from $30 to $20/share

∑

Objective

Probability

100

explorations, 25 successes and 75

failures

Probability

(Pr) of success = 1/4 and

the probability of failure =

3/4

EV

=

Pr(success)($40/share)

+

Pr(failure)($20/share)

=

1

4 ($ 4 0 /s h a re ) +

3 4

($ 2 0 /s h a re )

EV

E

V =

$ 2 5

/s h a re

Given:

Two possible

outcomes having payoffs X1 and

X2

Probabilities of

each outcome is given by Pr1 & Pr2

Generally,

expected value is written

as:

E(X)

=

Pr1X1

+

Pr2X2

+...

+

Prn Xn

63

Microeconomics

ECO402

VU

Variability

The extent to

which possible outcomes of an

uncertain event may

differ

Variability:

A Scenario

Suppose you

are choosing between two

part-time sales jobs that

have the same

expected

income ($1,500)

The first

job is based entirely on

commission.

The second is a

salaried position.

There are

two equally likely outcomes

in the first job--$2,000 for

a good sales job

and

$1,000

for a modestly successful

one.

The second

pays $1,510 most of the

time (.99 probability), but

you will earn $510 if

the

company

goes out of business (.01

probability).

Income

from Sales Jobs

Outcome

1

Outcome

2

Probability

Income($)

probability

Income($)

Expected

income

.5

2000

.5

1000

1500

Job

1: Commission

.99

1510

.01

510

1500

Job

2: Fixed salary

E(X1 )

= .5($2000)

+

.5($1000)

=

$1500

Job

2 Expected Income

E(X

2 ) =

.99($1510)

+

.01($510)

=

$1500

While

the expected values are

the same, the variability is

not.

Greater

variability from expected

values signals greater

risk.

Deviation

Difference

between expected payoff and

actual payoff

Deviations

from Expected Income

($)

Outcome

1

Deviation

Outcome

2

Deviation

Job

1

$2,000

$500

$1,000

-$500

Job

2

1,510

10

510

-900

Adjusting

for negative numbers

The

standard deviation measures

the square root of the

average of the squares of

the

deviations

of the payoffs associated

with each outcome from

their expected value.

The

standard deviation is

written:

σ

= Pr[X1 -E(X)2]

+Pr

[X2 -E(X)2]

1

2

64

Microeconomics

ECO402

VU

Calculating

Variance ($)

Deviation

Deviation

Deviation

Standard

Outcome

1

Squared

Outcome

2

Squared

Squared

Deviation

Job

1 $2,000

$250,000

$1,000

$250,000

$250,000

$500.00

Job

2 1,510

100

510

980,100

9,900

99.50

The

standard deviations of the

two jobs are:

σ1

=

0)

+

.5($250,00

.5($250,00

0

σ

1

=

$

250 , 000

σ

1

=

500

*Greater

Risk

σ

=

+

.01($980,1

.99($100

00)

2

σ

=

$

9 , 900

2

σ

=

99 .

50

2

The

standard deviation can be

used when there are

many outcomes instead of

only two.

An

Example

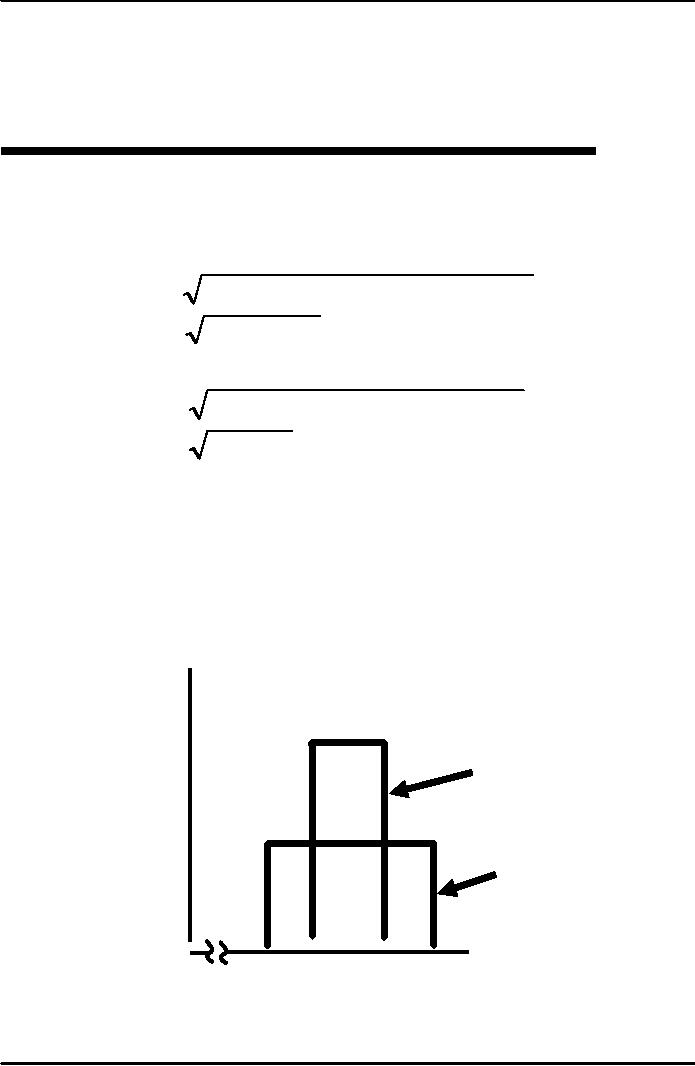

Job 1 is a job

in which the income ranges

from $1000 to $2000 in

increments of $100

that

are all equally

likely.

Job 2 is a job

in which the income ranges

from $1300 to $1700 in

increments of $100

that,

also, are all equally

likely.

Probability

Job

1 has greater

spread:

greater

standard

deviation

and

greater risk

than

Job 2.

0.2

Job

2

0.1

Job

1

Income

$1000

$1500

$2000

Outcome

Probabilities of Two Jobs

(unequal probability of

outcomes)

Job 1: greater

spread & standard

deviation

65

Microeconomics

ECO402

VU

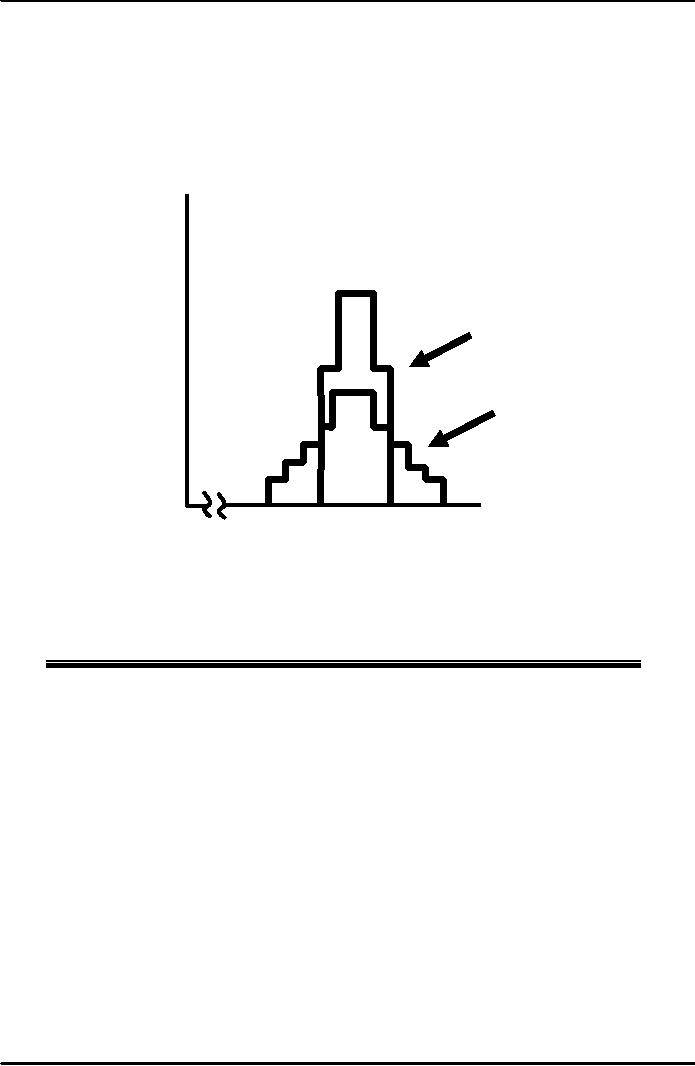

Peaked

distribution: extreme payoffs

are less likely

Decision

Making

A risk avoider

would choose Job 2: same

expected income as Job 1

with less risk.

Suppose we add

$100 to each payoff in Job 1

which makes the expected

payoff =

$1600.

Unequal

Probability Outcomes

The

distribution of payoffs

Probability

associated

with Job 1 has a

greater

spread and standard

deviation

than those with Job

2.

0.2

Job

2

0.1

Job

1

Income

$1000

$1500

$2000

Income

from Sales Jobs--Modified

($)

Deviation

Deviation

Deviation

Standard

Outcome

1

Squared

Outcome

2

Squared

Squared

Deviation

Job

1 $2,100

$250,000

$1,100

$250,000

$1,

600

$500

Job

2 1510

100

510

980,100

1,

500

99.50

Recall:

The standard deviation is

the square root of the

deviation squared.

Decision

making

Job 1: expected

income $1,600 and a standard

deviation of $500.

Job 2: expected

income of $1,500 and a

standard deviation of

$99.50

Which

job?

∑

Greater

value or less risk?

Example

Suppose a city

wants to deter people from

wrong parking.

The

alternatives ......

66

Microeconomics

ECO402

VU

Assumptions:

1)

Wrong parking saves a person

$5 in terms of time spent

searching for a parking

space.

2)

The driver is risk

neutral.

3)

Cost of apprehension is

zero.

A

fine of $5.01 would deter

the driver from double

parking.

Benefit of

wrong parking ($5) is less

than the cost ($5.01)

equals a net benefit that

is

less

than 0.

Increasing

the fine can reduce

enforcement cost:

A $50 fine

with a .1 probability of being

caught results in an expected

penalty of $5.

A $500 fine

with a .01 probability of

being caught results in an

expected penalty of

$5.

The

more risk averse drivers

are, the lower the

fine needs to be in order to be

effective.

67

Table of Contents:

- ECONOMICS:Themes of Microeconomics, Theories and Models

- Economics: Another Perspective, Factors of Production

- REAL VERSUS NOMINAL PRICES:SUPPLY AND DEMAND, The Demand Curve

- Changes in Market Equilibrium:Market for College Education

- Elasticities of supply and demand:The Demand for Gasoline

- Consumer Behavior:Consumer Preferences, Indifference curves

- CONSUMER PREFERENCES:Budget Constraints, Consumer Choice

- Note it is repeated:Consumer Preferences, Revealed Preferences

- MARGINAL UTILITY AND CONSUMER CHOICE:COST-OF-LIVING INDEXES

- Review of Consumer Equilibrium:INDIVIDUAL DEMAND, An Inferior Good

- Income & Substitution Effects:Determining the Market Demand Curve

- The Aggregate Demand For Wheat:NETWORK EXTERNALITIES

- Describing Risk:Unequal Probability Outcomes

- PREFERENCES TOWARD RISK:Risk Premium, Indifference Curve

- PREFERENCES TOWARD RISK:Reducing Risk, The Demand for Risky Assets

- The Technology of Production:Production Function for Food

- Production with Two Variable Inputs:Returns to Scale

- Measuring Cost: Which Costs Matter?:Cost in the Short Run

- A Firmís Short-Run Costs ($):The Effect of Effluent Fees on Firmsí Input Choices

- Cost in the Long Run:Long-Run Cost with Economies & Diseconomies of Scale

- Production with Two Outputs--Economies of Scope:Cubic Cost Function

- Perfectly Competitive Markets:Choosing Output in Short Run

- A Competitive Firm Incurring Losses:Industry Supply in Short Run

- Elasticity of Market Supply:Producer Surplus for a Market

- Elasticity of Market Supply:Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium

- Elasticity of Market Supply:The Industryís Long-Run Supply Curve

- Elasticity of Market Supply:Welfare loss if price is held below market-clearing level

- Price Supports:Supply Restrictions, Import Quotas and Tariffs

- The Sugar Quota:The Impact of a Tax or Subsidy, Subsidy

- Perfect Competition:Total, Marginal, and Average Revenue

- Perfect Competition:Effect of Excise Tax on Monopolist

- Monopoly:Elasticity of Demand and Price Markup, Sources of Monopoly Power

- The Social Costs of Monopoly Power:Price Regulation, Monopsony

- Monopsony Power:Pricing With Market Power, Capturing Consumer Surplus

- Monopsony Power:THE ECONOMICS OF COUPONS AND REBATES

- Airline Fares:Elasticities of Demand for Air Travel, The Two-Part Tariff

- Bundling:Consumption Decisions When Products are Bundled

- Bundling:Mixed Versus Pure Bundling, Effects of Advertising

- MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION:Monopolistic Competition in the Market for Colas and Coffee

- OLIGOPOLY:Duopoly Example, Price Competition

- Competition Versus Collusion:The Prisonersí Dilemma, Implications of the Prisoners

- COMPETITIVE FACTOR MARKETS:Marginal Revenue Product

- Competitive Factor Markets:The Demand for Jet Fuel

- Equilibrium in a Competitive Factor Market:Labor Market Equilibrium

- Factor Markets with Monopoly Power:Monopoly Power of Sellers of Labor