|

TECHNIQUE |

| << MATERIALS |

| VALUES >> |

offers

a good deal of obstruction to the pen,

however, so that a

really

good

line is impossible.

Thin

letter-paper is sometimes recommended for pen and

ink work,

chiefly on

account of its transparency,

which obviates the necessity

of re-

drawing

after a preliminary sketch

has been worked up in

pencil. Over

the

pencil study a sheet of the

letter-paper is placed on which the

final

drawing

may be made with much

deliberation. Bond paper,

however,

possesses

the similar advantage of transparency

besides affording a

better

texture for the

pen.

CHAPTER

III

TECHNIQUE

The

first requirement of a good pen technique

is a good Individual The

Line,

a line of feeling and quality. It is

usually a surprise to the

beginner Individual

to

be made aware that the

individual line is a thing of

consequence,--a Line

surprise

due, without doubt, to the

apparently careless methods of

some

successful

illustrators. It is to be borne in mind,

however, that some

illustrators

are successful in spite of their

technique rather than

because

of

it; and also that the

apparently free and easy

manner of some

admirable

technicians is in reality very

much studied, very

deliberate,

and

not at all to be confounded

with the unsophisticated

scribbling of the

beginner.

The student is apt to find it

just about as easy to draw

like Mr.

Pennell

as to write like Mr. Kipling.

The best way to acquire

such a

superb

freedom is to be very, very

careful and painstaking. To

appreciate

how

beautiful the individual

line may be one has but to

observe the rich,

decorative

stroke of Howard Pyle, Fig.

66, or that of Mucha, Fig.

65, the

tender

outline of Boutet de Monvel,

the telling, masterly sweep

of

Gibson,

or the short, crisp line of

Vierge or Rico. Compared with

any of

these

the line of the beginner

will be either feeble and tentative, or

harsh,

wiry,

and coarse.

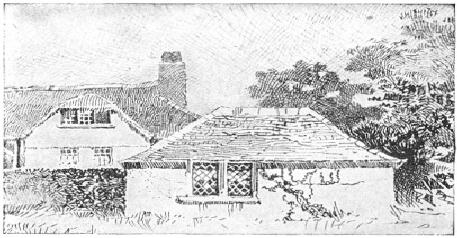

FIG.

6

B.

G. GOODHUE

FIG.

7

HERBERT

RAILTON

The

second requisite is Variety of

Line,--not merely variety of size

Variety

of

and

direction, but, since each

line ought to exhibit a

feeling for the Line

particular

texture which it is contributing to

express, variety of character.

Mr.

Gibson's manner of placing

very delicate gray lines

against a series

of

heavy black strokes exemplifies

some of the possibilities of

such

variety.

Observe, in Fig. 6, what

significance is imparted to the

heavy

lines

on the roof of the little

foreground building by the

foil of delicate

gray

lines in the sky and

surrounding roofs. This

conjunction was

employed

early by Mr. Herbert Railton,

who has made a beautiful

use of

it

in his quaint architectural

subjects. Mr. Railton's technique

is

remarkable

also for the varied

direction of line and its

expression of

texture.

Note this characteristic in

his drawing of buttresses, Fig.

7.

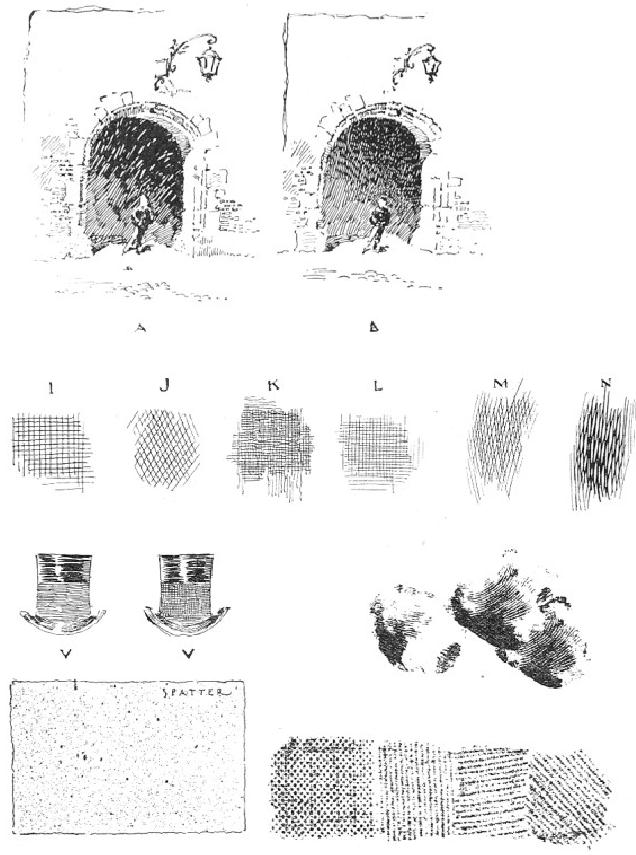

FIG.

8

B.

G. GOODHUE

FIG.

9

C.

D. M.

FIG.

10

C.

D. M.

The

third element of good technique is

Economy and Directness of Economy

of

Method.

A tone should not be built

up of a lot of meaningless strokes. Method

Each

line ought, sensibly and

directly, to contribute to the

ultimate result.

The

old mechanical process of

constructing tones by cross-hatching

is

now

almost obsolete. It is still employed by

modern pen draughtsmen,

but

it is only one of many resources, and is

used with nice

discrimination.

At times a cross-hatch is very desirable

and very

effective,--as,

for example, in affording a subdued

background for

figures

having small, high lights. A

very pretty use of it is

seen in the

tower

of Mr. Goodhue's drawing, Fig. 8.

Observe here how the

intimate

treatment

of the roofs is enhanced and relieved by

the foil of

closely-knit

hatch

on the tower-wall, and how

effective is the little area

of it at the

base

of the spire. The

cross-hatch also affords a satisfactory

method of

obtaining

deep, quiet shadows. See

the archway "B" in Fig. 9.

On the

whole,

however, the student is advised to

accustom himself to a

very

sparing

use of this expedient. Compare

the two effects in Fig. 9,

Some

examples

of good and bad cross-hatching are

illustrated in Fig. 10.

Those

marked

"I" and "J" may be set down

as bad, being too coarse.

The only

satisfactory

cross-hatch at a large scale

would seem to be that shown

in

"N,"

where lines cross at a sharp

angle; and this variety is

effectively

employed

by figure illustrators. Perhaps no

better argument against

the

necessity

for thus building up tones

could be adduced than the

little

drawing

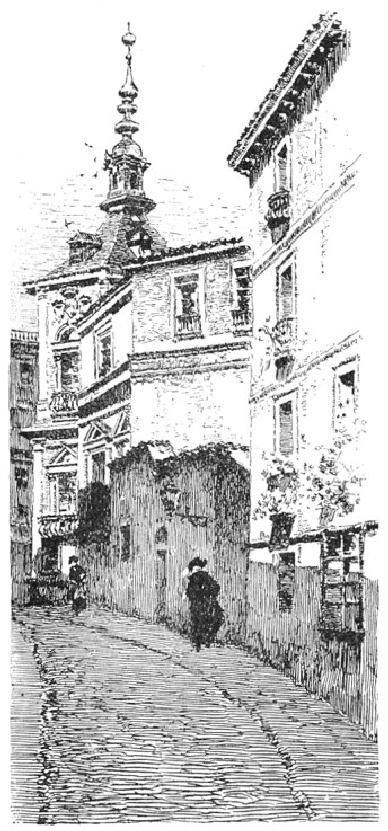

by Martin Rico, shown in

Fig. 11. Notice what a

beautiful

texture

he gives to the shadow where

it falls on the street, how it

differs

from

that on the walls, how

deep and closely knit it

all is, and yet

that

there

is absolutely no cross-hatching. Remark,

also, how the textures

of

the

walls and roof and sky

are obtained. The student

would do well to

copy

such a drawing as this, or a

portion of it, at least, on a

larger scale,

as

much can be learned from

it.

FIG.

11

MARTIN

RICO

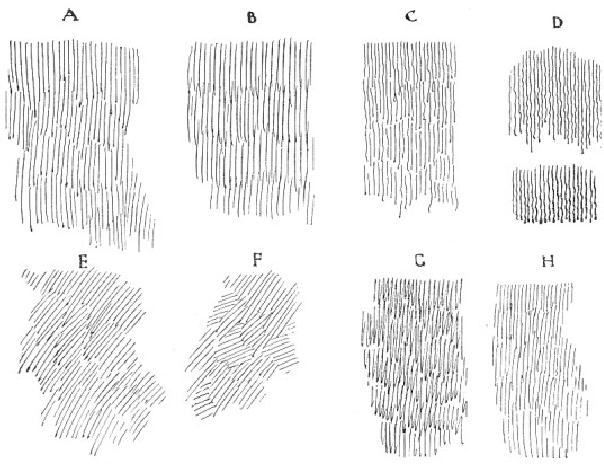

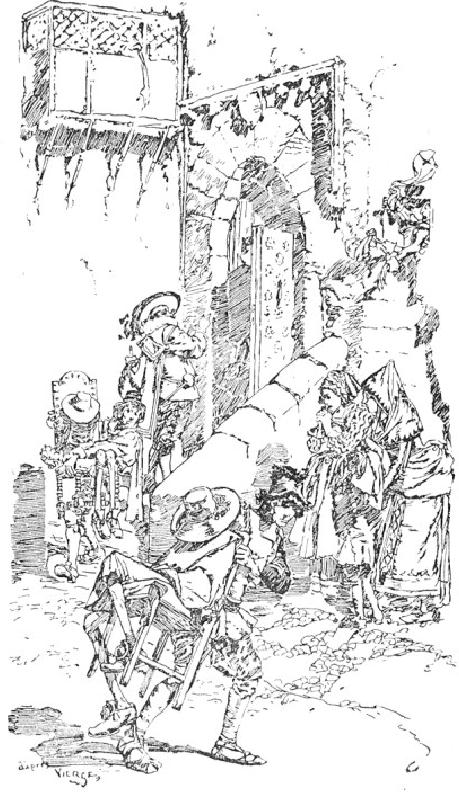

I

have shown various methods

of making a tone in Fig. 12.

It will be Methods

of

observed

that Rico's shadow, in Fig.

11, is made up of a combination of

Tone-Making

"B"

and "C," except that he uses

"B" horizontally, and makes

the line

heavy

and dragging. The clear,

crisp shadows of Vierge are also

worthy

of

study for the simplicity of

method. This is beautifully

illustrated in the

detail,

Fig. 13. It would be

impossible to suggest atmosphere

more

vibrating

with sunlight; a result due to

the transparency of the

shadows,

the

lines of which are sharp and

clean, with never a

suggestion of cross-

hatch.

Notice how the lines of

the architectural shadows are

stopped

abruptly

at times, giving an emphasis

which adds to the brilliancy

of the

effect.

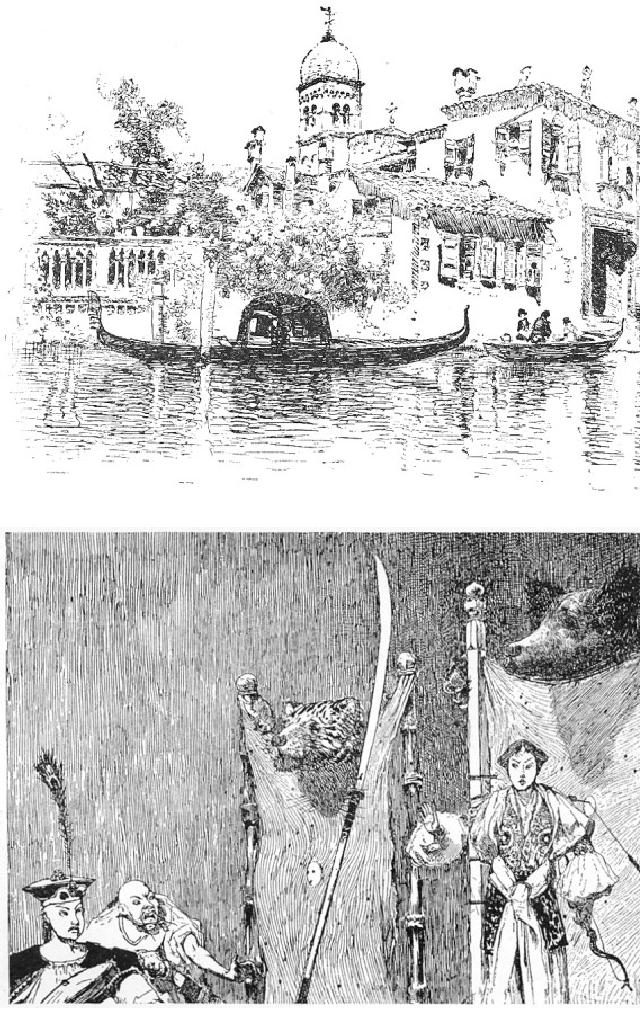

The drawing of the buildings

on the canal, by Martin

Rico, Fig.

14,

ought also to be carefully studied in

this connection. Observe

how

the

shadow-lines in this drawing, as in

that previously mentioned,

are

made

to suggest the direction of

the sunlight, which is high

in the

heavens.

An example of all that is

refined and excellent in pen

technique

is

the drawing by Mr. Alfred

Brennan, Fig. 15. The

student would do

well

to study this carefully for

its marvellous beauty of

line. There is

little

hatching, and yet the tones

are deep and rich. The

wall tone will be

found

to be made up similarly to "A" and "H" in

Fig. 12. The tone

"B" in

the

same Figure is made up of

lines which are thin at

the ends and big in

the

middle, fitting into each

other irregularly, and imparting a

texture

somewhat

different from that obtained

by the abrupt ending of

the

strokes

of "A." This method is also

employed by Brennan, and is a

very

effective

one. A good example of the

use of this character of

line

(unknitted,

however) is the drawing by Mr.

Leslie Willson, Fig. 16.

The

irregular

line "C" has good

possibilities for texture, and

the wavy

character

of "D" is most effective in

the rendering of shadows, giving

a

certain

vibration to the atmosphere. "E" and

"F" suggest a freer

method

of

rendering a tone; while "G"

shows a scribbling line that

is sometimes

employed

to advantage. The very interesting

texture of the coat, Fig.

17,

is

made with a horizontal line

having a similar return

stroke, as may be

noticed

where the rendering ends.

There are times when an

irresponsible

sort

of line is positively desirable,--say

for rough foreground

suggestion

or

for freeing the picture at

the edges.

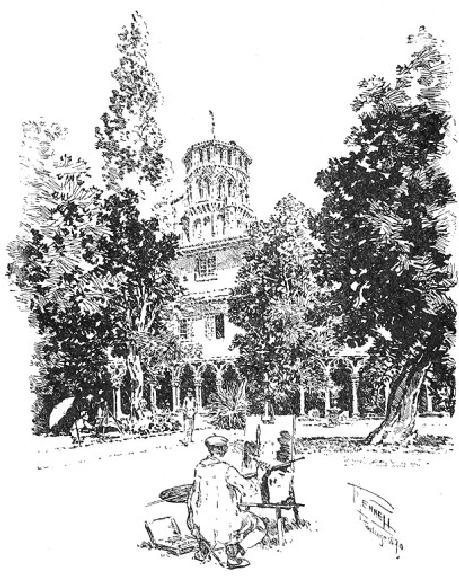

FIG.

12

C.

D. M.

FIG.

13

DANIEL

VIERGE

FIG.

14

FIG.

15

ALFRED

BREN

FIG.

16

LESLIE

WILLSON

I

have invariably found that

what presents the chief

difficulty to the Outline

student

of pen and ink is the management of the

Outline. When it is

realized

that, by mere outline, one may

express the texture of a coat or

a

tree

or a wall without any

rendering whatever, it will be seen

that nothing

in

pen drawing is really of so much

importance. Notice, for

example, the

wonderful

drawing of the dog in Fig.

34. Again, if a connected line

had

been

used to define the corners

of Railton's buttresses in Fig. 7

all the

texture,

would have been destroyed.

Instead of this he has used

a broken

outline,

sometimes omitting it altogether for a

considerable space. On the

ledges,

too, the lines are

broken. In Rico's drawing,

Fig. 11, all

the

outlines

may be observed to have a break here and

there. This broken

line

is particularly effective in out-door

subjects, as it helps to

suggest

sunlit

atmosphere as well as texture.

FIG.

17

DRAWING

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH

Architectural

outlines, however, are not

particularly subtle; it is

when

we

come to render anything with

vague boundaries, such as

foliage or

clouds

for example, that the

chief difficulties are

encountered. Foliage is

an

important element of landscape

drawing and deserves more

than

passing

consideration. To make a successful

rendering of a tree in pen

and

ink the tree must be first

well drawn in pencil. It is

absolutely

impossible

to obtain such a charming

effect of foliage as that

shown in

Mr.

Pennell's sketch, Fig. 18,

without the most painstaking

preparation in

pencil.

The success of this result

is not attributable merely to

the

difference

in textures, nor to the

direction or character of the

line; it is

first

of all a matter of good drawing.

The outline should be free

and

subtle

so as to suggest the edges of leafage,

and the holes near the

edges

should

be accented, otherwise they will be lost

and the tree will look

solid

and characterless. Observe, in the

same drawing, how Mr.

Pennell

suggests

the structure of the leafage by

the irregular outlines which

he

gives

to the different series of

lines, and which he emphasizes

by

bringing

the lines to an abrupt stop.

Observe also how the

stronger

texture

of the tree in Fig. 19 is obtained by

making the lines with

greater

abruptness.

Compare both of these Figures

with the foreground trees

by

the

same artist in Fig. 20.

The last is a brilliant

example of foliage

drawing

in pen and ink.

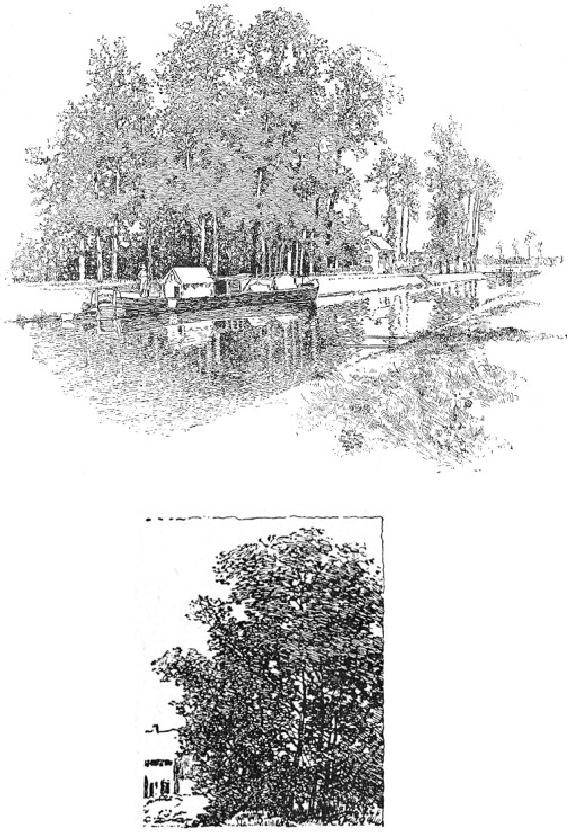

FIG.

18

JOSEPH

PENNELL

FIG.

19

JOSEPH

PENNELL

FIG.

20

JOSEPH

PENNELL

FIG.

21

E.

DANTAN

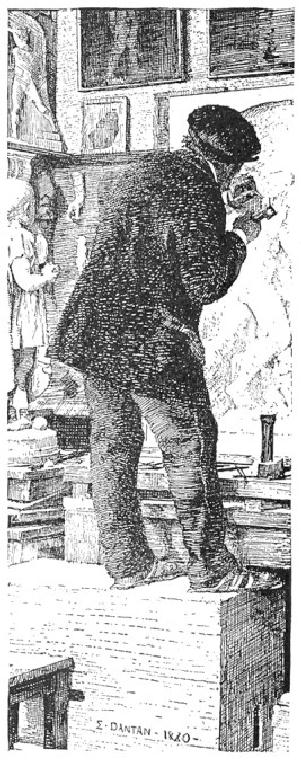

The

matter of Textures is very

important, and the student

should learn Textures

to

differentiate them as much as possible.

This is done, as I have

already

said,

by differences in the size and character of

the line, and in the

closeness

or openness of the rendering.

Observe the variety of

textures in

the

drawing of the sculptor by

Dantan, Fig. 21. The coat is

rendered by

such

a cross-hatch as "N" in Fig. 10,

made horizontally and with

heavy

lines.

In the trousers the lines do

not cross but fit in

together. This is an

excellent

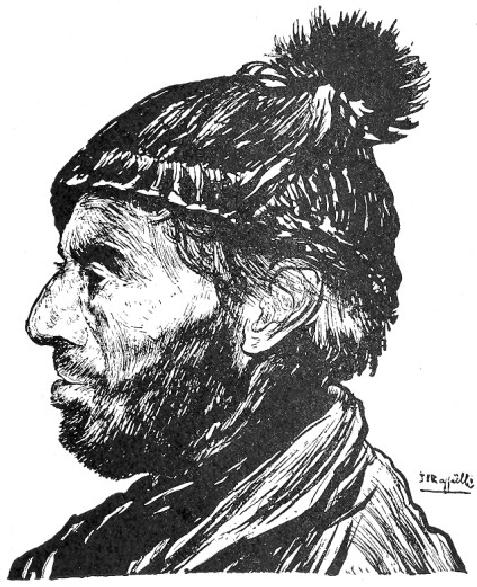

example for study, as is also

the portrait by Raffa�lli,

Fig. 22.

The

textures in the latter

drawing are wonderfully well

conveved,--the

hard,

bony face, the stubby beard,

and the woolen cap with

its tassel in

silhouette.

For the expression of

texture with the least

effort the drawings

of

Vierge are incomparable. The

architectural drawing by Mr. Gregg

in

Fig.

50 is well worth careful

study in this connection, as

are all of

Herbert

Railton's admirable drawings of

old English houses. (I

recommend

the study of Mr. Railton's

work with a good deal of

reservation,

however. While it is admirable in

respect of textures and

fascinating

in its color, the values

are likely to be most

unreal, and the

mannerisms

are so pronounced and so

tiresome that I regard it as

much

inferior

to that of Mr. Pennell, whose

architecture always appears,

at

least,

to have been honestly drawn

on the spot.)

FIG.

22

J.

F. RAFFAčLLI

The

hats in Fig. 10 are merely suggestions to

the student in the study

of

elementary

combinations of line in expressing

textures.

As

the mechanical processes of

Reproduction have much to do

with Drawing

for

determining

pen methods they

become important

factors for Reproduction

consideration.

While their waywardness and

inflexibility are the cause

of

no

little distress to the

illustrator, the limitations of

processes cannot be

said,

on the whole, to make for

inferior standards in drawing, as will

be

seen

by the following rules which

they impose, and for which a

strict

regard

will be found most

advisable.

First:

Make each line clear and

distinct. Do not patch up a

weak line or

leave

one which has been broken or

blurred by rubbing, for

however

harmless

or even interesting it may

seem in your original it will

almost

certainly

be neither in the reproduction.

When you make mistakes,

erase

the

offensive part completely,

or, if you are working on

Bristol-board

and

the area of unsatisfactoriness be

considerable, paste a fresh

piece of

paper

over it and redraw.

Second:

Keep your work open. Aim

for economy of line. If a

shadow

can

be rendered with twenty strokes do not

crowd in forty, as you

will

endanger

its transparency. Remember

that in reproduction the

lines tend

to

thicken and so to crowd out

the light between them.

This is so

distressingly

true of newspaper reproduction that in

drawings for this

purpose

the lines have to be

generally very thin, sharp, and

well apart.

The

above rule should be particularly

regarded in all cases where

the

drawing

is to be subject to much reduction.

The degree of reduction

of

which

pen drawings are susceptible is

not, as is commonly

supposed,

subject

to rule. It all depends on

the scale of the

technique.

Third:

Have the values few and

positive. It is necessary to keep

the

gray

tones pretty distinct to prevent

the relation of values being

injured,

for

while the gray tones darken

in proportion to the degree of

reduction,

the

blacks cannot, of course,

grow blacker. A gray tone

which may be

light

and delicate in the original,

will, especially if it be closely

knit,

darken

and thicken in the printing.

These rules are most

strictly to be

observed

when drawing for the

cheaper classes of publications.

For book

and

magazine work, however,

where the plates are touched

up by the

engraver,

and the values in a measure restored,

the third rule is not

so

arbitrary.

Nevertheless, the beginner

who has ambitions in this

direction

will

do well not to put

difficulties in his own way

by submitting work

not

directly

printable.

There

are a number of more or less

fanciful expedients employed in Some

modern

pen work which may be noted

here, and which are

illustrated in Fanciful

Fig.

10. The student is advised,

however, to resort to them as

little as Expedients

possible,

not only because he is

liable to make injudicious use of

them,

but

because it is wiser for him

to cultivate the less

meretricious

possibilities

of the instrument.

"Spatter

work" is a means of obtaining a

delicate printable

tone,

consisting

of innumerable little dots of ink

spattered on the paper.

The

process

is as follows: Carefully cover

with a sheet of paper all

the

drawing

except the portion which is

to be spattered, then take a

tooth-

brush,

moisten the ends of the

bristles consistently with

ink, hold the

brush,

back downwards, in the left

hand, and with a wooden

match or

tooth-pick

rub the bristles toward you

so

that the ink will spray

over the

paper.

Particular, care must be

taken that the brush is

not so loaded with

ink

that it will spatter in blots. It is

well, therefore, to try it

first on a