|

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE |

| << ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE |

| EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA >> |

CHAPTER

IX.

ROMAN

ARCHITECTURE--Continued.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: Same as for Chapter VIII.

Also, Guhl and Kohner,

Life

of the

Ancient

Greeks and Romans.

Adams, Ruins

of the Palace of Spalato.

Burn, Rome

and

the

Campagna.

Cameron, Roman

Baths. Mau, tr. by

Kelcey, Pompeii,

its Life and

Art.

Mazois,

Ruines

de Pompeii. Von

Presuhn, Die

neueste Ausgrabungen zu

Pompeii.

Wood,

Ruins

of Palmyra and Baalbec.

THE

ETRUSCAN STYLE. Although

the first Greek architects

were employed in

Rome

as early as 493 B.C., the architecture of

the Republic was practically

Etruscan

until

nearly 100 B.C. Its monuments,

consisting mainly of city walls, tombs,

and

temples,

are all marked by a general

uncouthness of detail, denoting a

lack of artistic

refinement,

but they display considerable

constructive skill. In the Etruscan

walls we

meet

with both polygonal and regularly coursed

masonry; in both kinds the true

arch

appears

as the almost universal form for gates

and openings. A famous example

is

the

Augustan Gate at Perugia, a

late work rebuilt about 40

B.C., but thoroughly

Etruscan

in style. At Volaterræ (Volterra) is

another arched gate, and in

Perugia

fragments

of still another appear built into the

modern walls.

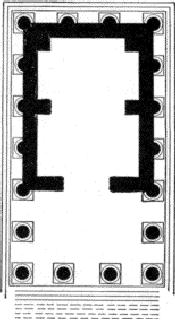

FIG.

51.--TEMPLE FORTUNA VIRILIS.

PLAN.

The

Etruscans built both structural and

excavated tombs; they consisted in

general of

a

single chamber with a slightly

arched or gabled roof,

supported in the larger

tombs

on

heavy square piers. The

interiors were covered with

pictures; externally there

was

little

ornament except about the

gable and doorway. The latter had a

stepped or

moulded

frame with curious crossettes

or

ears projecting laterally at the top.

The

gable

recalled the wooden roofs of

Etruscan temples, but was

coarse in detail,

especially

in its mouldings. Sepulchral

monuments of other types are

also met with,

such

as cippi

or

memorial pillars, sometimes in

groups of five on a single

pedestal

(tomb

at Albano).

Among

the temples of Etruscan style that of

Jupiter

Capitolinus on the

Capitol at

Rome,

destroyed by fire in 80 B.C.,

was the chief. Three narrow

chambers side by

side

formed a cella nearly square

in plan, preceded by a hexastyle porch of

huge

Doric,

or rather Tuscan, columns

arranged in three aisles, widely

spaced and carrying

ponderous

wooden architraves. The roof

was of wood; the cymatium and

ornaments,

as

well as the statues in the pediment, were

of terra-cotta, painted and gilded.

The

details

in general showed acquaintance with

Greek models, which appeared

in

debased

and awkward imitations of triglyphs,

cornices, antefixæ,

etc.

GREEK

STYLE. The

victories of Marcellus at Syracuse, 212

B.C., Fabius Maximus at

Tarentum

(209 B.C.), Flaminius (196 B.C.), Mummius

(146 B.C.), Sulla (86

B.C.),

and

others in the various Greek

provinces, steadily increased the

vogue of Greek

architecture

and the number of Greek artists in Rome.

The temples of the last two

centuries

B.C., and some of earlier

date, though still Etruscan in plan,

were in many

cases

strongly Greek in the character of their

details. A few have remained to

our

time

in tolerable preservation. The temple of

Fortuna

Virilis (really

of Fors Fortuna),

of

the second century (?) B.C., is a

tetrastyle prostyle pseudoperipteral

temple with a

high

podium

or

base, a typical Etruscan

cella, and a deep porch, now

walled up, but

thoroughly

Greek in the elegant details of

its Ionic order (Fig. 51). Two

circular

temples,

both called erroneously Temples

of Vesta,

one at Rome near the

Cloaca

Maxima,

the other at Tivoli, belong among the

monuments of Greek style. The

first

was

probably dedicated to Hercules, the

second probably to the Sibyls; the

latter

being

much the better preserved of the two.

Both were surrounded by

peristyles of

eighteen

Corinthian columns, and probably

covered by domical roofs with

gilded

bronze

tiles. The Corinthian order

appears here complete with

its modillion

cornice,

but

the crispness of the detail and the

fineness of the execution are

Greek and not

Roman.

These temples date from

about 72 B.C., though the one at

Rome was

probably

rebuilt in the first century A.D. (Fig.

52).

IMPERIAL

ARCHITECTURE; AUGUSTAN AGE. Even

in the temples of Greek

style

Roman

conceptions of plan and composition are

dominant. The Greek architect

was

not

free to reproduce textually

Greek designs or details,

however strongly he might

impress

with the Greek character whatever he

touched. The demands of

imperial

splendor

and the building of great edifices of

varied form and complex structure,

like

the

thermæ and amphitheatres, called for new

adaptations and combinations of

planning

and engineering. The reign of Augustus

(27 B.C.-14 A.D.) inaugurated

the

imperial

epoch, but many works erected

before and after his reign

properly belong to

the

Augustan age by right of style. In

general, we find in the works of this

period the

happiest

combination of Greek refinement with

Roman splendor. It was in

this

period

that Rome first assumed the

aspect of an opulent and splendid

metropolis,

though

the way had been prepared for this by the

regularization and adornment of

the

Roman Forum and the erection of many

temples, basilicas, fora,

arches, and

theatres

during the generation preceding the

accession of Augustus. His reign

saw the

inception

or completion of the portico of Octavia,

the Augustan forum, the Septa

Julia,

the first Pantheon, the adjoining

Thermæ of Agrippa, the theatre of

Marcellus,

the

first of the imperial palaces on the

Palatine, and a long list of

temples, including

those

of the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux), of

Mars Ultor, of Jupiter Tonans on

the

Capitol,

and others in the provinces; besides

colonnades, statues, arches, and

other

embellishments

almost without number.

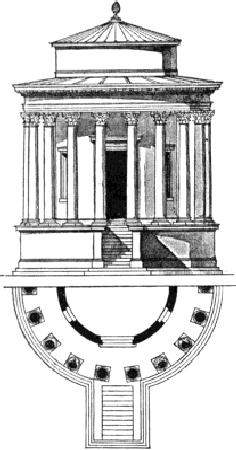

FIG.

52.--CIRCULAR TEMPLE.

TIVOLI.

LATER

IMPERIAL WORKS. With the

successors of Augustus splendor

increased to

almost

fabulous limits, as, for

instance, in the vast extent and the

prodigality of ivory

and

gold in the famous Golden

House of Nero. After the

great fire in Rome,

presumably

kindled by the agents of this emperor, a

more regular and

monumental

system

of street-planning and building was

introduced, and the first

municipal

building-law

was decreed by him. To the reign of

Vespasian (6879 A.D.) we

owe

the

rebuilding in Roman style and with the

Corinthian order of the temple of

Jupiter

Capitolinus,

the Baths of Titus, and the beginning of the

Flavian amphitheatre or

Colosseum.

The two last-named edifices both stood on

the site of Nero's

Golden

House,

of which the greater part was demolished

to make way for them. During the

last

years of the first century the arch of

Titus was erected, the Colosseum

finished,

amphitheatres

built at Verona, Pola, Reggio, Tusculum,

Nîmes (France),

Constantine

(Algiers),

Pompeii and Herculanum (these

last two cities and Stabiæ

rebuilt after the

earthquake

of 63 A.D.), and arches, bridges, and

temples erected all over the

Roman

world.

The

first part of the second century was

distinguished by the splendid

architectural

achievements

of the reign of Hadrian (117138

A.D.) in Rome and the

provinces,

especially

Athens. Nearly all his works

were marked by great dignity

of conception as

well

as beauty of detail. During the latter

part of the century a very interesting

series

of

buildings were erected in the Hauran

(Syria), in which Greek and Arab

workmen

under

Roman direction produced

examples of vigorous stone

architecture of a

mingled

Roman and Syrian

character.

The

most-remarkable thermæ of Rome

belong to the third century--those

of

Caracalla

(211217 A.D.) and of Diocletian (284305

A.D.)--their ruins to-day

ranking

among the most imposing

remains of antiquity. In Syria the

temples of the

Sun

at Baalbec and Palmyra (273 A.D., under

Aurelian), and the great palace

of

Diocletian

at Spalato, in Dalmatia (300 A.D.),

are still the wonder of the

few

travellers

who reach those distant

spots.

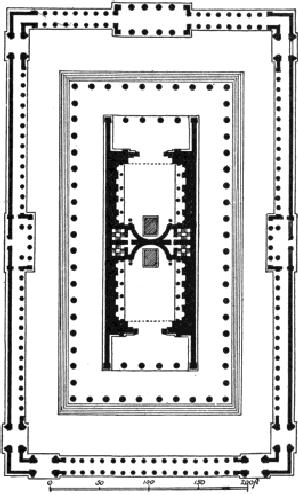

FIG.

53.--TEMPLE OF VENUS AND ROME.

PLAN.

While

during the third and fourth centuries

there was a marked decline

in purity and

refinement

of detail, many of the later works of the

period display a

remarkable

freedom

and originality in conception. But these

works are really not Roman,

they

are

foreign, that is, provincial

products; and the transfer of the capital

to Byzantium

revealed

the increasing degree in which Rome

was coming to look to the

East for her

strength

and her art.

TEMPLES.

The

Romans built both rectangular and

circular temples, and there

was

much

variety in their treatment. In the

rectangular temples a high podium,

or

basement,

was substituted for the Greek

stepped stylobate, and the prostyle

plan

was

more common than the peripteral. The

cella was relatively short

and wide, the

front

porch inordinately deep, and

frequently divided by longitudinal

rows of

columns

into three aisles. In most

cases the exterior of the cella in

prostyle temples

was

decorated by engaged columns. A

barrel vault gave the interior an

aspect of

spaciousness

impossible with the Greek system of a

wooden ceiling supported

on

double

ranges of columns. In the place of

these, free or engaged

columns along the

side-walls

received the ribs of the vaulting.

Between these ribs the

ceiling was richly

panelled,

or coffered and sumptuously gilded. The

temples of Fortuna

Virilis and

of

Faustina

at

Rome (the latter built 141 A.D., and

its ruins incorporated into the

modern

church of S. Lorenzo in Miranda), and the

beautiful and admirably

preserved

Maison

Carrée, at

Nîmes (France) (4 A.D.) are

examples of this type. The temple

of

Concord, of which

only the podium remains, and the small

temple of Julius (both

of

these

in the Forum) illustrate another form of

prostyle temple in which the porch

was

on

a long side of the cella.

Some of the larger temples

were peripteral. The temple

of

the

Dioscuri

(Castor

and Pollux) in the Forum, was

one of the most magnificent

of

of

Venus

and Rome,

east of the Forum, designed by the

Emperor Hadrian about

130

A.D.

(Fig. 53). It was a vast

pseudodipteral edifice containing two

cellas in one

structure,

their statue-niches or apses

meeting back to back in the

centre. The temple

stood

in the midst of an imposing columnar

peribolus entered by

magnificent

gateways.

Other important temples have

already been mentioned on p.

91.

Besides

the two circular temples already

described, the temple of Vesta,

adjoining the

House

of the Vestals, at the east end of the

Forum should be mentioned. At

Baalbec

is

a circular temple whose

entablature curves inward between the

widely-spaced

columns

until it touches the cella in the middle

of each intercolumniation. It

illustrates

the caprices of design which sometimes

resulted from the disregard of

tradition

and the striving after originality (273

A.D.).

THE

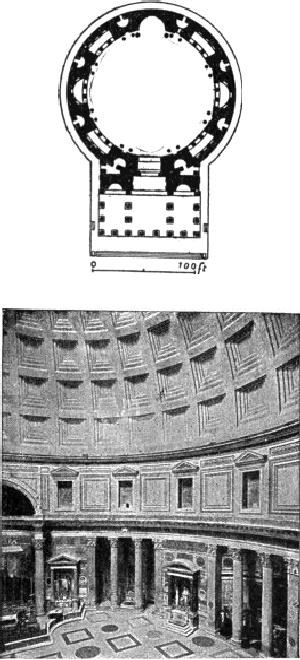

PANTHEON. The

noblest of all circular temples of

Rome and of the world was

the

Pantheon. It

was built by Hadrian, 117138 A.D., on the

site of the earlier

rectangular

temple of the same name

erected by Agrippa. It measures 142

feet in

diameter

internally; the wall is 20 feet thick and

supports a hemispherical

dome

rising

to a height of 140 feet (Figs. 54, 55).

Light is admitted solely through a

round

opening

28 feet in diameter at the top of the

dome, the simplest and most

impressive

method

of illumination conceivable. The rain and snow that

enter produce no

appreciable

effect upon the temperature of the vast

hall. There is a single

entrance,

with

noble bronze doors,

admitting directly to the interior,

around which seven

niches,

alternately rectangular and semicircular

in plan and fronted by Corinthian

columns,

lighten, without weakening, the mass of

the encircling wall. This wall

was

originally

incrusted with rich marbles, and the

great dome, adorned with

deep

coffering

in rectangular panels, was

decorated with rosettes and mouldings in

gilt

stucco.

The dome appears to have

been composed of numerous

arches and ribs,

filled

in

and finally coated with concrete. A

recent examination of a denuded

portion of its

inner

surface has convinced the writer that the

interior panelling was

executed after,

and

not during, its construction, by

hewing the panels out of the mass of

brick and

concrete,

without regard to the form and position of the

origin skeleton of

ribs.

FIG.

54.--PLAN OF THE

PANTHEON.

FIG.

55.--INTERIOR OF THE

PANTHEON.

The

exterior (Fig. 56) was less

successful than the interior. The gabled

porch of

twelve

superb granite columns 50

feet high, three-aisled in plan

after the Etruscan

mode,

and covered originally by a ceiling of

bronze, was a rebuilding with

the

materials

and on the plan of the original pronaos of the

Pantheon of Agrippa. The

circular

wall behind it is faced with fine

brickwork, and displays, like the

dome,

many

curious arrangements of discharging

arches, reminiscences of

traditional

constructive

precautions here wholly useless and

fictitious because only

skin-deep.

A

revetment of marble below and

plaster above once concealed

this brick facing. The

portico,

in spite of its too steep

gable (once filled with a

"gigantomachia" in gilt

bronze)

and its somewhat awkward association with

a round building, is nevertheless

a

noble work, its capitals in

Pentelic marble ranking

among the finest known

examples

of the Roman Corinthian. Taken as a

whole, the Pantheon is one of

the

great

masterpieces of the world's

architecture.

FIG.

56.--EXTERIOR OF THE

PANTHEON.

(From

model in Metropolitan Museum, New

York.)

FORA

AND BASILICAS. The

fora were the places for

general public assemblage.

The

chief

of those in Rome, the Forum

Magnum, or

Forum

Romanum,

was at first merely

an

irregular vacant space,

about and in which, as the focus of the

civic life, temples,

halls,

colonnades, and statues gradually

accumulated. These chance

aggregations the

systematic

Roman mind reduced in time to

orderly and monumental form;

successive

emperors

extended them and added new fora at

enormous cost and with

great

splendor

of architecture. Those of Julius,

Augustus, Vespasian, and Nerva

(or

Domitian),

adjoining the Roman Forum,

were magnificent enclosures

surrounded by

high

walls and single or double

colonnades. Each contained a

temple or basilica,

besides

gateways, memorial columns or

arches, and countless statues. The

Forum

of

Trajan

surpassed

all the rest; it covered an area of

thirty-five thousand square

yards,

and

included, besides the main area,

entered through a triumphal arch, the

Basilica

Ulpia,

the temple of Trajan, and his

colossal Doric column of Victory.

Both in size

and

beauty it ranked as the chief

architectural glory of the city (Fig.

57). The six fora

together

contained thirteen temples,

three basilicas, eight triumphal

arches, a mile of

colonnades

covered large tracts of the city,

affording sheltered communication

in

every

direction, and here and there

expanding into squares or gardens

surrounded by

peristyles.

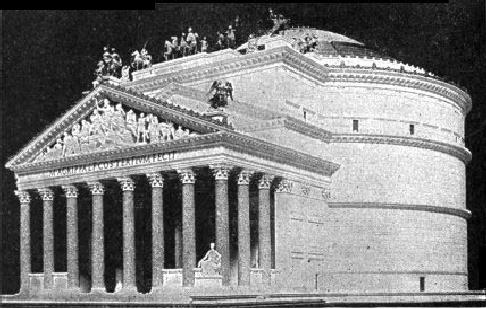

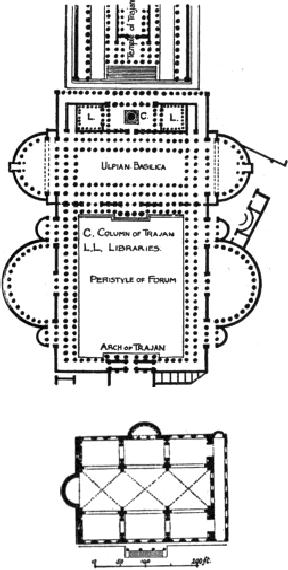

FIG.

57.--FORUM AND BASILICA OF TRAJAN.

FIG.

58.--BASILICA OF CONSTANTINE.

PLAN.

The

public business of Rome, both

judicial and commercial, was

largely transacted in

the

basilicas,

large buildings consisting

usually of a wide and lofty central

nave

flanked

by lower side-aisles, and terminating at

one or both ends in an apse

or

semicircular

recess called the tribune, in which

were the seats for the

magistrates.

The

side-aisles were separated from the

nave by columns supporting a

clearstory

wall,

pierced by windows above the

roofs of the side-aisles. In some

cases the latter

were

two stories high, with galleries; in

others the central space was

open to the sky,

as

at Pompeii, suggesting the derivation of

the basilica from the open

square

surrounded

by colonnades, or from the forum itself, with which we

find it usually

associated.

The most important basilicas in

Rome were the Sempronian, the

Æmilian

(about

54 B.C.), the Julian

in the

Forum Magnum (51 B.C.), and the Ulpian

in

the

Forum

of Trajan (113 A.D.). The last two were

probably open basilicas, only

the

side-aisles

being roofed. The Ulpian (Fig. 57)

was the most magnificent of all, and

in

conjunction

with the Forum of Trajan formed one of

the most imposing of

those

monumental

aggregations of columnar architecture

which contributed so largely to

the

splendor of the Roman

capital.

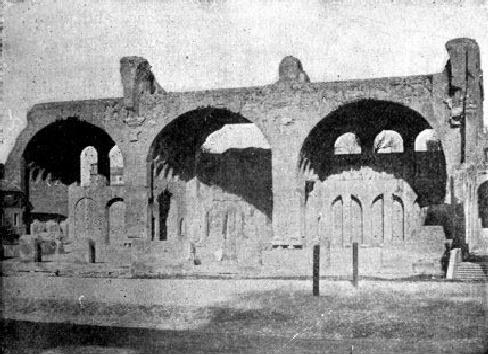

FIG.

59.--BASILICA OF CONSTANTINE.

RUINS.

These

monuments frequently suffered from the

burning of their wooden roofs. It

was

Constantine

who completed the first vaulted and

fireproof basilica, begun by

his

predecessor

and rival, Maxentius, on the site of the

former Temple of Peace

(Figs.

58,

59). Its design reproduced on a grand

scale the plan of the tepidarium-halls

of

the

thermæ, the side-recesses of which were

converted into a continuous side-aisle

by

piercing

arches through the buttress-walls that

separated them. Above the

imposing

vaults

of these recesses and under the

cross-vaults of the nave were

windows

admitting

abundant light. A narthex, or

porch, preceded the hall at one

end; there

were

also a side entrance from the

Via Sacra, and an apse or

tribune for the

magistrates

opposite each of these

entrances. The dimensions of the main hall

(325

×

85 feet), the height of its vault (117

feet), and the splendor of its

columns and

incrustations

excited universal admiration, and

exercised a powerful influence

on

later

architecture.

THERMÆ.

The

leisure of the Roman people

was largely spent in the

great baths, or

thermæ, which

took the place substantially of the

modern club. The

establishments

erected

by the emperors for this purpose were

vast and complex congeries of

large

and

small halls, courts, and

chambers, combined with a masterly

comprehension of

artistic

propriety and effect in the sequence of

oblong, square, oval, and

circular

apartments,

and in the relation of the greater to the

lesser masses. They were

a

combination

of the Greek palæstra

with the

Roman balnea, and

united in one

harmonious

design great public

swimming-baths, private baths for

individuals and

families,

places for gymnastic exercises and

games, courts, peristyles,

gardens, halls

for

literary entertainments, lounging-rooms,

and all the complex accommodation

required

for the service of the whole establishment. They

were built with apparent

disregard

of cost, and adorned with splendid

extravagance. The earliest were

the

Baths

of Agrippa (27

B.C.) behind the Pantheon; next may be

mentioned those of

Titus, built on the

substructions of Nero's Golden

House. The remains of the

Thermæ

of Caracalla (211

A.D.) form the most extensive

mass of ruins in Rome,

and

clearly display the admirable

planning of this and similar

establishments.

A

gigantic block of buildings

containing the three great

halls for cold, warm, and hot

baths,

stood in the centre of a vast

enclosure surrounded by private

baths, exedræ,

and

halls for lecture-audiences and other

gatherings. The enclosure was

adorned with

statues,

flower-gardens, and places for out-door

games. The Baths

of Diocletian (302

A.D.)

embodied this arrangement on a still

more extensive scale; they

could

accommodate

3,500 bathers at once, and their ruins

cover a broad territory near

the

railway

terminus of the modern city. The church of S. Maria

degli Angeli was

formed

by

Michael Angelo out of the tepidarium

of

these baths--a colossal hall 340 ×

87

feet,

and 90 feet high. The original

vaulting and columns are

still intact, and the

whole

interior most imposing, in

spite of later stucco

disfigurements. The circular

laconicum

(sweat-room)

serves as the porch to the present

church. It was in the

building

of these great halls that

Roman architecture reached

its most original and

characteristic

expression. Wholly unrelated to any

foreign model, they

represent

distinctively

Roman ideals, both as to plan and

construction.

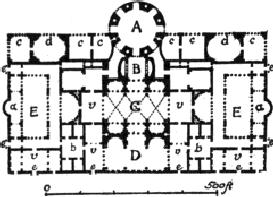

FIG.

60.--THERMÆ OF CARACALLA. PLAN OF

CENTRAL BLOCK.

A,

Caldarium, or Hot Bath; B,

Intermediate Chamber; C, Tepidarium, or

Warm Bath; D,

Frigidarium,

or Cold Bath; E, Peristyles; a,

Gymnastic Rooms; b, Dressing

Rooms; c,

Cooling

Rooms; d, Small Courts; e,

Entrances; v, Vestibules.

FIG.

61.--ROMAN THEATRE. (HERCULANUM.)

(From

model.)

PLACES

OF AMUSEMENT. The

earliest Roman theatres

differed from the Greek in

having

a nearly semicircular plan, and in being

built up from the level ground,

not

excavated

in a hillside (Fig. 61). The first

theatre was of wood, built by

Mummius

145

B.C., and it was not until ninety years

later that stone was first

substituted for

the

more perishable material, in the

theatre of Pompey. The Theatre

of Marcellus

(2313

B.C.) is in part still extant, and

later theatres in Pompeii,

Orange (France),

and

in the Asiatic provinces are in

excellent preservation. The orchestra

was not, as

in

the Greek theatre, reserved for the

choral dance, but was given

up to spectators of

rank;

the stage was adorned with a

permanent architectural background of

columns

and

arches, and sometimes roofed with

wood, and an arcade or

colonnade

surrounded

the upper tier of seats. The

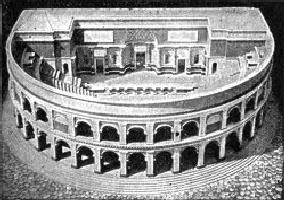

amphitheatre was a still

more distinctively

Roman

edifice. It was elliptical in plan,

surrounding an elliptical arena, and

built up

with

continuous encircling tiers of

seats. The earliest stone

amphitheatre was

erected

by

Statilius Taurus in the time of Augustus.

It was practically identical in

design with

the

later and much larger Flavian

amphitheatre, commonly known as the

Colosseum,

begun

by Vespasian and completed 82 A.D. (Fig.

62). This immense

structure

measured

607 × 506 feet in plan and was 180 feet

high; it could

accommodate

eighty-seven

thousand spectators. Engaged

columns of the Tuscan, Ionic,

and

Corinthian

orders decorated three

stories of the exterior; the fourth was a

nearly

unbroken

wall with slender Corinthian pilasters.

Solidly constructed of

travertine,

concrete,

and tufa, the Colosseum, with its

imposing but monotonous

exterior,

almost

sublime by its scale and

seemingly endless repetition, but

lacking in

refinement

or originality of detail and dedicated to

bloody and cruel sports, was

a

characteristic

product of the Roman character and

civilization. At Verona,

Pola,

Capua,

and many cities in the foreign provinces

there are well-preserved

remains of

similar

structures.

Closely

related to the amphitheatre were the

circus and the stadium. The Circus

Maximus

between

the Palatine and Aventine hills

was the oldest of those in

Rome.

That

erected by Caligula and Nero on the

site afterward partly occupied by

St.

Peter's,

was more splendid, and is

said to have been capable of

accommodating over

three

hundred thousand spectators after

its enlargement in the fourth century.

The

long,

narrow race-course was divided into two

nearly equal parts by a low

parapet,

the

spina, on which

were the goals (metæ) and many

small decorative structures

and

columns.

One end of the circus, as of the stadium

also, was semicircular; the

other

was

segmental in the circus, square in the

stadium; a colonnade or arcade ran

along

the

top of the building, and the entrances and

exits were adorned with

monumental

arches.

FIG.

62.--COLOSSEUM. HALF

PLAN.

FIG.

63.--ARCH OF CONSTANTINE.

(From

model in Metropolitan Museum, New

York.)

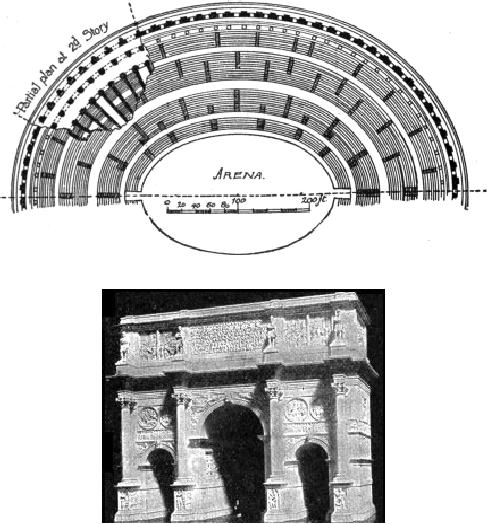

TRIUMPHAL

ARCHES AND COLUMNS. Rome

and the provincial cities

abounded

in

monuments commemorative of victory,

usually single or triple

arches with engaged

columns

and rich sculptural adornments, or single

colossal columns

supporting

statues.

The arches were characteristic

products of Roman design, and

some of them

deserve

high praise for the excellence of their

proportions and the elegance of

their

details.

There were in Rome in the

second century A.D., thirty-eight of

these

monuments.

The Arch

of Titus (7182

A.D.) is the simplest and most

perfect of

those

still extant in Rome; the

arch of Septimius

Severus in the

Forum (203 A.D.)

and

that of Constantine

(330

A.D.) near the Colosseum,

are more sumptuous

but

less

pure in detail. The last-named

was in part enriched with sculptures

taken from

the

earlier arch of Trajan. The statues of

Dacian captives on the attic

(attic

=

a

species

of subordinate story added

above the main cornice) of this arch

were a

fortunate

addition, furnishing a raison-d'être

for the

columns and broken

entablatures

on

which they rest. Memorial columns of

colossal size were erected

by several

emperors,

both in Rome and abroad. Those of

Trajan

and of

Marcus

Aurelius are

still

standing in Rome in perfect

preservation. The first was 140

feet high including

the

pedestal and the statue which surmounted

it; its capital marked the

height of the

ridge

levelled by the emperor for the forum on which the

column stands. Its most

striking

peculiarity is the spiral band of

reliefs winding around the

shaft from bottom

to

top and representing the Dacian campaigns

of Trajan. The other column is of

similar

design and dimensions, but greatly

inferior to the first in execution.

Both are

really

towers, with interior stair-cases

leading to the top.

TOMBS.

The

Romans developed no special and

national type of tomb, and few of

their

sepulchral monuments were of

large dimensions. The most

important in Rome

were

the pyramid of Caius

Cestius (late

first century B.C.), and the circular

tombs of

Cecilia

Metella (60

B.C.), Augustus

(14

A.D.) and Hadrian, now the

Castle of

S.

Angelo (138 A.D.). The latter

was composed of a huge cone

of marble supported

on

a cylindrical structure 230 feet in

diameter standing on a square

podium 300 feet

long

and wide. The cone probably

once terminated in the gilt

bronze pine-cone now

in

the Giardino della Pigna of the

Vatican. In the Mausoleum of Augustus a

mound of

earth

planted with trees crowned a

similar circular base of

marble on a podium 220

feet

square, now buried.

The

smaller tombs varied greatly

in size and form. Some were

vaulted chambers,

with

graceful internal painted

decorations of figures and vine

patterns combined with

low-relief

enrichments in stucco. Others

were designed in the form of altars

or

sarcophagi,

as at Pompeii; while others again

resembled ædiculæ, little

temples,

shrines,

or small towers in several

stories of arches and columns, as at

St. Rémy

(France).

PALACES

AND DWELLINGS. Into their

dwellings the Romans carried all their

love

of

ostentation and personal luxury. They

anticipated in many details the comforts

of

modern

civilization in their furniture, their plumbing and

heating, and their utensils.

Their

houses may be divided into four classes:

the palace, the villa, the domus

or

ordinary

house, and the insula

or

many-storied tenement built in compact

blocks.

The

first three alone concern

us, and will be taken up in the above

order.

The

imperial palaces

on the

Palatine Hill comprised a wide

range in style and

variety

of

buildings, beginning with the first

simple house of Augustus (26

B.C.), burnt and

rebuilt

3 A.D. Tiberius, Caligula, and Nero

added to the Augustan group;

Domitian

rebuilt

a second time and enlarged the

palace of Augustus, and Septimius

Severus

remodelled

the whole group, adding to it his own

extraordinary seven-storied

palace,

the

Septizonium. The ruins of these

successive buildings have

been carefully

excavated,

and reveal a remarkable combination of

dwelling-rooms, courts,

temples,

libraries,

basilicas, baths, gardens,

peristyles, fountains, terraces, and

covered

passages.

These were adorned with a

profusion of precious marbles,

mosaics,

columns,

and statues. Parts of the demolished

palace of Nero were

incorporated in

the

substructions of the Baths of Titus. The

beautiful arabesques and plaster

reliefs

which

adorned them were the inspiration of much

of the fresco and stucco

decoration

of

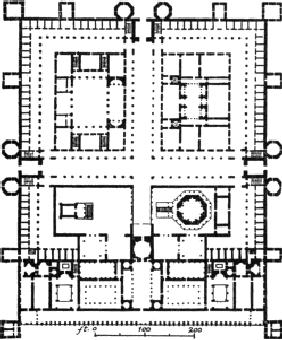

the Italian Renaissance. At Spalato, in

Dalmatia, are the extensive ruins of

the

great

Palace

of Diocletian, which

was laid out on the plan of a Roman

camp, with

two

intersecting avenues (Fig. 64). It

comprised a temple, mausoleum,

basilica, and

other

structures besides those

portions devoted to the purposes of a

royal residence.

FIG.

64.--PALACE OF DIOCLETIAN.

SPALATO.

The

villa

was

in reality a country palace, arranged

with special reference to the

prevailing

winds, exposure to the sun and shade, and the

enjoyment of a wide

prospect.

Baths, temples, exedræ,

theatres, tennis-courts, sun-rooms, and

shaded

porticoes

were connected with the house

proper, which was built around two

or

three

interior courts or peristyles.

Statues, fountains, and colossal

vases of marble

adorned

the grounds, which were laid out in

terraces and treated with all the

fantastic

arts of the Roman landscape-gardener. The

most elaborate and

extensive

villa

was that of Hadrian, at Tibur

(Tivoli); its ruins,

covering hundreds of

acres,

form

one of the most interesting

spots to visit in the neighborhood of

Rome.

There

are few remains in Rome of the

domus

or

private house. Two, however,

have

left

remarkably interesting ruins--the

Atrium

Vestæ, or

House of the Vestal

Virgins,

east

of the Forum, a well-planned and

extensive house surrounding a

cloister or

court;

and the House

of Livia,

so-called, on the Palatine Hill, the

walls and

decorations

of which are excellently preserved. The

typical Roman house in

a

provincial

town is best illustrated by the ruins of

Pompeii and Herculanum, which,

buried

by an eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.,

have been partially

excavated since

1721.

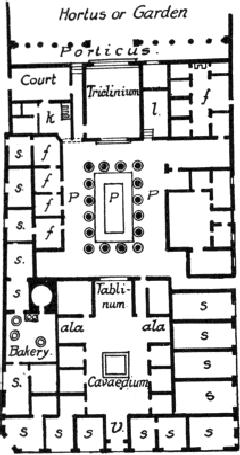

FIG.

65.--HOUSE OF PANSA,

POMPEII.

s,

Shops; v, Vestibule; f, Family

Rooms; k, Kitchen; l, Lavarium; P, P, P,

Peristyles.

The

Pompeiian house (Fig. 65)

consisted of several courts or

atria,

some of which

were

surrounded by colonnades and called

peristyles. The front

portion was reserved

for

shops, or presented to the street a wall

unbroken save by the entrance; all

the

rooms

and chambers opened upon the interior

courts, from which alone they

borrowed

their light. In the brilliant climate of

southern Italy windows were little

needed,

as sufficient light was admitted by the

door, closed only by portières for

the

most

part; especially as the family life

was passed mainly in the shaded

courts, to

which

fountains, parterres of shrubbery,

statues, and other adornments lent

their

inviting

charm. The general plan of these

houses seems to have been of

Greek origin,

as

well as the system of decoration used on

the walls. These, when not

wainscoted

with

marble, were covered with

fantastic, but often artistic,

painted decorations, in

which

an imaginary architecture as of metal, a

fantastic and arbitrary

perspective,

illusory

pictures, and highly finished figures

were the chief elements.

These were

executed

in brilliant colors with excellent

effect. The houses were lightly built,

with

wooden

ceilings and roofs instead of

vaulting, and usually with but one

story on

account

of the danger from earthquakes. That the

workmanship and decoration

were

in

the capital often superior to what

was to be found in a provincial town

like

Pompeii,

is evidenced by beautiful wall-paintings

and reliefs discovered in Rome

in

1879

and now preserved in the Museo delle

Terme. More or less

fragmentary

remains

of Roman houses have been

found in almost every corner of the

Roman

empire,

but nowhere exhibiting as completely as

in Pompeii the typical

Roman

arrangement.

WORKS

OF UTILITY. A word

should be said about Roman

engineering works,

which

in many cases were designed with an

artistic sense of proportion and

form

which

raises them into the domain of genuine

art. Such were especially the

bridges,

in

which a remarkable effect of monumental

grandeur was often produced

by the

form

and proportions of the arches and piers,

and an appropriate use of rough

and

dressed

masonry, as in the Pons Ælius

(Ponte S. Angelo), the great

bridge at

Alcantara

(Spain), and the Pont du Gard, in

southern France. The aqueducts

are

impressive

rather by their length, scale, and

simplicity, than by any special

refinements

of design, except where their

arches are treated with some

architectural

decoration

to form gates, as in the Porta Maggiore,

at Rome.

MONUMENTS:

(Those

which have no important

extant remains are given in

italics.)

TEMPLES:

Jupiter

Capitolinus, 600

B.C.; Ceres,

Liber, and Libera, 494

B.C. (ruins of later

rebuilding

in S. Maria in Cosmedin); first

T. of Concord (rebuilt

in Augustan age), 254

B.C.;

first

marble temple in

portico

of Metellus, by a

Greek, Hermodorus, 143

B.C.;

temples

of Fortune at Præneste and at

Rome, and of "Vesta" at

Rome, 8378 B.C.; of

"Vesta"

at Tivoli, and of Hercules at

Cori, 72 B.C.; first

Pantheon, 27

B.C. In Augustan

Age

temples of Apollo,

Concord rebuilt, Dioscuri,

Julius,

Jupiter

Stator,

Jupiter

Tonans,

Mars

Ultor, Minerva (at

Rome and

Assisi), Maison Carrée at

Nîmes, Saturn; at

Puteoli,

Pola,

etc. T.

of Peace;

T.

Jupiter Capitolinus,

rebuilt 70 A.D.; temple at

Brescia. Temple of

Vespasian,

96 A.D.; also of

Minerva in

Forum of Nerva; of

Trajan, 117

A.D.; second

Pantheon;

T. of Venus and Rome at

Rome, and of Jupiter

Olympius at Athens, 135138

A.D.;

Faustina, 141 A.D.; many in

Syria; temples of Sun at

Rome,

Baalbec, and Palmyra,

cir.

273 A.D.; of Romulus, 305 A.D. (porch S.

Cosmo and Damiano). PLACES OF

ASSEMBLY:

FORA--Roman,

Julian, 46 B.C.; Augustan, 4042

B.C.; of

Peace, 75

A.D.;

Nerva,

97 A.D.; Trajan (by

Apollodorus of Damascus, 117 A.D.)

BASILICAS: Sempronian,

Æmilian,

1st century B.C.; Julian, 51

B.C.; Septa

Julia, 26

B.C.; the Curia, later

rebuilt

by

Diocletian, 300 A.D. (now Church of S.

Adriano); at

Fano, 20 A.D.

(?); Forum and

Basilica

at Pompeii, 60 A.D.; of Trajan; of

Constantine, 310324 A.D. THEATRES (th.)

and

AMPHITHEATRES (amp.): th.

Pompey, 55

B.C.; of Balbus

and

of Marcellus, 13 B.C.; th.

and

amp. at Pompeii and

Herculanum; Colosseum at Rome, 7882

A.D.; th. at Orange

and

in Asia Minor; amp. at

Albano, Constantine, Nîmes,

Petra, Pola, Reggio,

Trevi,

Tusculum,

Verona, etc.; amp. Castrense

at Rome, 96 A.D. Circuses and

stadia at Rome.

THERMÆ:

of Agrippa, 27 B.C.; of

Nero; of

Titus, 78 A.D. Domitian, 90

A.D.; Caracalla,

211

A.D.; Diocletian, 305 A.D.;

Constantine, 320

A.D.; "Minerva Medica," 3d or

4th

century

A.D. ARCHES: of

Stertinius, 196

B.C.; Scipio, 190

B.C.; Augustus, 30

B.C.; Titus,

7182

A.D.; Trajan, 117

A.D.; Severus, 203 A.D.;

Constantine, 320 A.D.; of

Drusus,

Dolabella,

Silversmiths, 204 A.D.; Janus

Quadrifrons, 320 A.D. (?); all at

Rome. Others

at

Benevento, Ancona, Rimini in

Italy; also at Athens, and

at Reims and St. Chamas

in

France.

Columns of Trajan,

Antoninus,

Marcus Aurelius at

Rome, others at

Constantinople,

Alexandria, etc. TOMBS: along Via Appia

and Via Latina, at Rome;

Via

Sacra

at Pompeii; tower-tombs at St.

Rémy in France; rock-cut at

Petra; at Rome, of

Caius

Cestius

and Cecilia Metella, 1st

century B.C.; of Augustus, 14

A.D.; Hadrian, 138 A.D.

PALACES and

PRIVATE

HOUSES: On

Palatine, of Augustus, Tiberius,

Nero, Domitian,

Septimius

Severus, Elagabalus;

Villa of Hadrian at Tivoli;

palaces of Diocletian at

Spalato

and

of

Constantine at

Constantinople. House of Livia on

Palatine (Augustan period);

of

Vestals,

rebuilt by Hadrian, cir. 120 A.D.

Houses at Pompeii and

Herculanum, cir. 60

79

A.D.; Villas of Gordianus

("Tor' de' Schiavi," 240

A.D.), and of

Sallust at

Rome and

of

Pliny at

Laurentium.

14.

Lanciani:

Ancient

Rome in the Light of Recent

Discoveries, p.

89.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.