|

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS |

| << EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS |

| RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES >> |

CHAPTER

XXI.

RENAISSANCE

ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY--Continued.

THE

ADVANCED RENAISSANCE AND

DECLINE.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before,

Burckhardt, Cicognara, Fergusson,

Palustre. Also,

Gauthier,

Les

plus beaux edifices de

Gênes.

Geymüller, Les

projets primitifs pour

la

basilique

de St. Pierre de Rome.

Gurlitt, Geschichte

des Barockstiles in Italien.

Letarouilly,

Édifices

de Rome Moderne;

Le

Vatican.

Palladio, The

Works of A. Palladio.

CHARACTER

OF THE ADVANCED RENAISSANCE. It

was inevitable that the study

and

imitation of Roman architecture

should lead to an increasingly

literal rendering

of

classic details and a closer

copying of antique compositions. Toward

the close of

the

fifteenth century the symptoms began to

multiply of the approaching reign

of

formal

classicism. Correctness in the

reproduction of old Roman forms

came in time

to

be esteemed as one of the chief of

architectural virtues, and in the

following

period

the orders became the principal

resource of the architect. During the

so-called

Cinquecento,

that is, from the close of the fifteenth

century to nearly or quite 1550,

architecture

still retained much of the freedom and

refinement of the Quattrocento.

There

was meanwhile a notable

advance in dignity and amplitude of

design,

especially

in the internal distribution of

buildings. Externally the orders

were freely

used

as subordinate features in the decoration

of doors and windows, and in court

arcades

of the Roman type. The lantern-crowned

dome upon a high drum was

developed

into one of the noblest of architectural

forms. Great attention

was

bestowed

upon all subordinate features; doors and

windows were treated with

frames

and pediments of extreme elegance and

refinement; all the cornices and

mouldings

were proportioned and profiled with the

utmost care, and the balustrade

was

elaborated into a feature at once

useful and highly ornate. Interior

decoration

was

even more splendid than

before, if somewhat less

delicate and subtle;

relief

enrichments

in stucco were used with

admirable effect, and the greatest

artists

exercised

their talents in the painting of

vaults and ceilings, as in P. del Té

at

Mantua,

by Giulio

Romano (14921546),

and the Sistine Chapel at Rome,

by

Michael

Angelo. This period is

distinguished by an exceptional number of

great

architects

and buildings. It was ushered in by

Bramante

Lazzari, of Urbino

(1444

1514),

and closed during the career of

Michael

Angelo Buonarotti (14751564);

two

names

worthy to rank with that of Brunelleschi. Inferior

only to these in architectural

genius

were Raphael

(14831520),

Baldassare

Peruzzi (14811536),

Antonio

da San

Gallo

the Younger (14851546),

and G.

Barozzi da Vignola (15071572),

in Rome;

Giacopo

Tatti Sansovino (14791570),

in Venice, and others almost

equally

illustrious.

This period witnessed the

erection of an extraordinary series of

palaces,

villas,

and churches, the beginning and much of the

construction of St. Peter's

at

Rome,

and a complete transformation in the

aspect of that city.

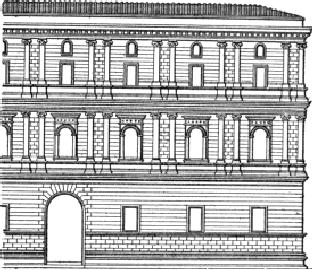

FIG.

166.--FAÇADE OF THE GIRAUD

PALACE, ROME.

BRAMANTE'S

WORKS. While

precise time limits cannot

be set to architectural

styles,

it is not irrational to date this period

from the maturing of Bramante's

genius.

While

his earlier works in Milan

belong to the Quattrocento (S. M.

delle Grazie, the

sacristy

of San Satiro, the extension of the

Great Hospital), his later

designs show the

classic

tendency very clearly. The charming

Tempietto

in the court

of S. Pietro in

Montorio

at Rome, a circular temple-like

chapel (1502), is composed of

purely

classic

elements. In the P.

Giraud (Fig.

166) and the great Cancelleria

Palace,

pilasters

appear in the external composition, and

all the details of doors and

windows

betray the results of classic study, as

well as the refined taste of their

system

of arches on columns with the Roman

system of superposed

arcades

independent

of the court wall. In 1506 Bramante began

the rebuilding of St.

Peter's

for

Julius II. and the construction of a new and

imposing papal palace

adjoining it on

the

Vatican hill. Of this colossal group of

edifices, commonly known as the Vatican,

he

executed the greater Belvedere court

(afterward divided in two by the Library

and

the

Braccio Nuovo), the lesser

octagonal court of the Belvedere, and the

court of San

Damaso,

with its arcades afterward

frescoed by Raphael and his

school. Besides

these,

the cloister of S. M. della Pace, and

many other works in and out of

Rome,

reveal

the impress of Bramante's genius,

alike in their admirable

plans and in the

harmony

and beauty of their details.

FLORENTINE

PALACES. The P.

Riccardi long remained the

accepted type of

palace

in

Florence. As we have seen, it

was imitated in the Strozzi

palace, as late as 1489,

with

greater perfection of detail, but with no

radical change of conception. In

the

P.

Gondi,

however, begun in the following

year by Giuliano

da San Gallo (1445

1516),

a more pronounced classic

spirit appears, especially in the

court and the

interior

design. Early in the 16th century classic

columns and pediments began to

be

used

as decorations for doors and windows; the

rustication was confined

to

basements

and corner-quoins, and niches, loggias,

and porches gave variety of

light

and

shade to the façades (P.

Bartolini, by

Baccio

d'Agnolo;

P.

Larderel, 1515,

by

Dosio;

P.

Guadagni, by

Cronaca;

P.

Pandolfini, 1518,

attributed to Raphael). In the

P.

Serristori, by

Baccio d'Agnolo (1510), pilasters

were applied to the

composition

of

the façade, but this example was not

often followed in

Florence.

ROMAN

PALACES. These

followed a different type. They

were usually of great

size,

and

built around ample courts with

arcades of classic model in two or

three stories.

The

broad street façade in three

stories with an attic or mezzanine

was crowned with

a

rich cornice. The orders were

sparingly used externally, and

effect was sought

principally

in the careful proportioning of the

stories, in the form and distribution

of

the

square-headed and arched openings, and in

the design of mouldings,

string-

courses,

cornices, and other details. The

piano

nobile, or

first story above the

basement,

was given up to suites of

sumptuous reception-rooms and halls,

with

magnificent

ceilings and frescoes by the great

painters of the day, while antique

statues

and reliefs adorned the courts,

vestibules, and niches of these

princely

dwellings.

The Massimi

palace,

by Peruzzi, is an interesting example of

this type.

The

Vatican, Cancelleria, and Giraud

palaces have already been

mentioned; other

notable

palaces are the Palma (1506) and

Sacchetti (1540), by A. da San Gallo

the

Younger;

the Farnesina, by

Peruzzi, with celebrated fresco

decorations designed by

Raphael;

and the Lante (1520) and Altemps (1530), by

Peruzzi. But the noblest

creation

of this period was the

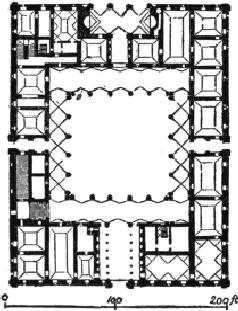

FIG.

167.--PLAN OF FARNESE

PALACE.

FARNESE

PALACE, by many

esteemed the finest in Italy. It was

begun in 1530 for

Alex.

Farnese (Paul III.) by A. da San

Gallo the Younger, with Vignola's

collaboration.

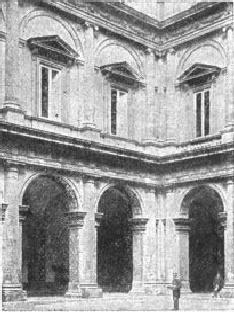

The simple but admirable plan is shown in

Fig. 167, and the

courtyard,

the most imposing in Italy, in Fig. 168.

The exterior is monotonous, but

the

noble cornice by Michael

Angelo measurably redeems this

defect. The fine

vaulted

columnar entrance vestibule, the court

and the salons,

make up an ensemble

worthy

of the great architects who designed it.

The loggia toward the river was

added

by

G.

della Porta in

1580.

VILLAS.

The Italian

villa of this pleasure-loving period

afforded full scope for the

most

playful fancies of the architect,

decorator, and landscape gardener. It

comprised

usually

a dwelling, a casino

or

amusement-house, and many minor edifices,

summer-

houses,

arcades, etc., disposed in

extensive grounds laid out with

terraces, cascades,

and

shaded alleys. The style was

graceful, sometimes trivial, but

almost always

pleasing,

making free use of stucco

enrichments, both internally and

externally, with

abundance

of gilding and frescoing. The Villa

Madama (1516), by

Raphael, with

stucco-decorations

by Giulio Romano, though incomplete and

now dilapidated, is a

noted

example of the style. More complete, the

Villa

of Pope Julius, by

Vignola

(1550),

belongs by its purity of style to this

period; its façade well

exemplifies the

simplicity,

dignity, and fine proportions of this

master's work. In addition to

these

Roman

villas may be mentioned the V.

Medici (1540, by

Annibale

Lippi; now

the

French

Academy of Rome); the Casino

del Papa in the

Vatican Gardens, by Pirro

Ligorio

(1560); the

V.

Lante,

near Viterbo, and the V.

d'Este, at Tivoli,

as displaying

among

almost countless others the

Italian skill in combining

architecture and

gardening.

FIG.

168.--ANGLE OF COURT OF FARNESE

PALACE, ROME.

CHURCHES

AND CHAPELS. This

period witnessed the building of a few

churches

of

the first rank, but it was especially

prolific in memorial, votive, and

sepulchral

chapels

added to churches already

existing, like the Chigi

Chapel of S. M.

del

Popolo,

by Raphael. The earlier churches of this

period generally followed

antecedent

types,

with the dome as the central feature

dominating a cruciform plan, and

simple,

unostentatious

and sometimes uninteresting exteriors.

Among them may be

mentioned:

at Pistoia, S. M. del Letto and

S.

M. dell' Umiltà, the

latter a fine

domical

rotunda by Ventura

Vitoni (1509), with

an imposing vestibule; at

Venice,

S.

Salvatore, by

Tullio

Lombardo (1530), an

admirable edifice with

alternating

domical

and barrel-vaulted bays; S.

Georgio dei Grechi (1536), by

Sansovino,

and

S.

M. Formosa; at Todi, the Madonna

della Consolazione (1510), by

Cola

da

Caprarola, a

charming design with a high dome and four

apses; at Montefiascone, the

Madonna

delle Grazie, by

Sammichele

(1523),

besides several churches at

Bologna,

Ferrara,

Prato, Sienna, and Rome of

almost or quite equal

interest. In these

churches

one

may trace the development of the dome as

an external feature, while in

S.

Biagio, at

Montepulciano, the effort was

made by Ant.

da San Gallo the Elder

to

combine

with it the contrasting lines of two

campaniles, of which, however, but

one

was

completed.

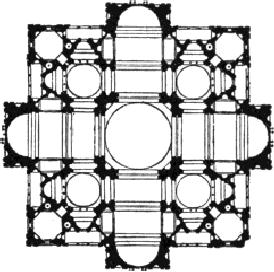

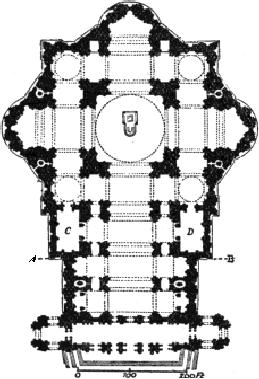

FIG.

169.--ORIGINAL PLAN OF ST.

PETER'S, ROME.

ST.

PETER'S. The

culmination of Renaissance church

architecture was reached in

St.

Peter's, at

Rome. The original project of

Nicholas V. having lapsed with

his death, it

was

the intention of Julius II. to erect on

the same site a stupendous

mausoleum over

the

monument he had ordered of Michael

Angelo. The design of Bramante,

who

began

its erection in 1506, comprised a

Greek cross with apsidal

arms, the four

angles

occupied by domical chapels and

loggias within a square outline

(Fig. 169).

The

too hasty execution of this

noble design led to the

collapse of two of the arches

under

the dome, and to long delays

after Bramante's death in 1514.

Raphael,

Giuliano

da San Gallo, Peruzzi, and A. da

San Gallo the Younger

successively

supervised

the works under the popes from Leo X. to

Paul III., and devised a

vast

number

of plans for its completion. Most of

these involved fundamental

alterations

of

the original scheme, and were

motived by the abandonment of the

proposed

monument

of Julius II.; a church, and not a

mausoleum, being in

consequence

required.

In 1546 Michael Angelo was

assigned by Paul III. to the works, and

gave

final

form to the general design in a

simplified version of Bramante's plan

with more

massive

supports, a square east front with a

portico for the chief entrance, and

the

unrivalled

Dome, which is

its most striking feature.

This dome, slightly altered

and

improved

in curvature by della Porta

after M. Angelo's death in 1564,

was

completed

by D.

Fontana in 1604. It is

the most majestic creation of

the

Renaissance,

and one of the greatest architectural

conceptions of all history. It

measures

140 feet in internal diameter, and with

its two shells rises from a

lofty

drum,

buttressed by coupled Corinthian

columns, to a height of 405 feet to the

top

of

the lantern. The church, as left by Michael

Angelo, was harmonious in

its

proportions,

though the single order used

internally and externally dwarfed by

its

colossal

scale the vast dimensions of the

edifice. Unfortunately in 1606 C.

Maderna

was

employed by Paul V. to lengthen the

nave by two bays, destroying

the

proportions

of the whole, and hiding the dome from

view on a near approach. The

present

tasteless façade was

Maderna's work. The splendid atrium or

portico added

(162967),

by Bernini, as an

approach, mitigates but does not

cure the ugliness and

pettiness

of this front.

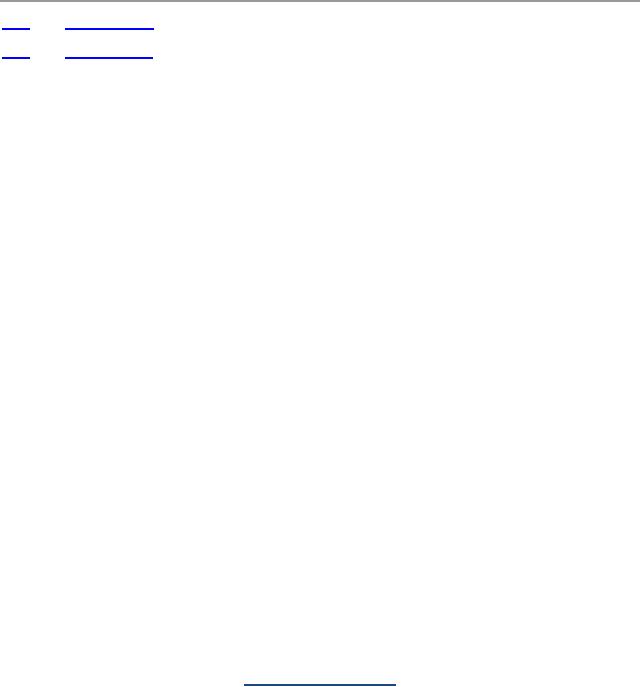

FIG.

170.--PLAN OF ST. PETER'S,

ROME, AS NOW STANDING.

The

portion below the line

A,

B,

and the side chapels

C,

D,

were added by

Maderna.

The

remainder represents Michael

Angelo's plan.

St.

Peter's as thus completed (Fig. 170) is

the largest church in existence, and

in

many

respects is architecturally worthy of its

pre-eminence. The central aisle,

nearly

600

feet long, with its

stupendous panelled and gilded vault, 83

feet in span, the

vast

central area and the majestic

dome, belong to a conception

unsurpassed in

majestic

simplicity and effectiveness. The

construction is almost excessively

massive,

but

admirably disposed. On the other hand the

nave is too long, and the

details not

only

lack originality and interest, but

are also too large and

coarse in scale,

dwarfing

the

whole edifice. The interior (Fig. 171) is

wanting in the sobriety of color

that

befits

so stately a design; it suggests

rather a pagan temple than a

Christian basilica.

These

faults reveal the decline of

taste which had already set in

before Michael

Angelo

took charge of the work, and which

appears even in the works of that

master.

THE

PERIOD OF FORMAL CLASSICISM.

With the

middle of the 16th century the

classic

orders began to dominate all

architectural design. While

Vignola, who wrote a

treatise

upon the orders, employed them with

unfailing refinement and judgment,

his

contemporaries

showed less discernment and

taste, making of them an end

rather

than

a means. Too often mere

classical correctness was

substituted for the

fundamental

qualities of original invention ind

intrinsic beauty of composition.

The

innovation

of colossal orders extending through

several stories, while it gave

to

exterior

designs a certain grandeur of

scale, tended to coarseness and

even vulgarity

of

detail. Sculpture and ornament

began to lose their refinement; and while

street-

architecture

gained in monumental scale, and

public squares received a

more stately

adornment

than ever before, the street-façades

individually were too often

bare and

uninteresting

in their correct formality. In the interiors of

churches and large

halls

there

appears a struggle between a

cold and dignified simplicity and a

growing

tendency

toward pretentious sham. But

these pernicious tendencies did not

fully

mature

till the latter part of the century, and the

half-century after 1540 or 1550

was

prolific of notable works in both

ecclesiastical and secular architecture.

The

names

of Michael Angelo and Vignola,

whose careers began in the

preceding period;

of

Palladio and della Porta (15411604)

in Rome; of Sammichele and Sansovino

in

Verona

and Venice, and of Galeazzo Alessi in

Genoa, stand high in the ranks

of

architectural

merit.

FIG.

171.--INTERIOR OF ST. PETER'S,

ROME.

CHURCHES.

The

type established by St.

Peter's was widely imitated

throughout

Italy.

The churches in which a Greek or Latin

cross is dominated by a high

dome

rising

from a drum and terminating in a lantern, and is

treated both internally and

externally

with Roman Corinthian pilasters and

arches, are almost

numberless.

Among

the best churches of this type is the

Gesù

at

Rome, by Vignola (1568), with a

highly

ornate interior of excellent

proportions and a less interesting

exterior, the

façade

adorned with two stories of orders and

great flanking volutes over

the sides.

Two

churches at Venice, by Palladio--S.

Giorgio Maggiore (1560;

façade by

Scamozzi, 1575) and

the Redentore--offer a

strong contrast to the Gesù, in

their

cold

and almost bare but pure and

correct design. An imitation of

Bramante's plan

for

St. Peter's appears in

S.

M. di Carignano, at

Genoa, by Galeazzo

Alessi (1500

72),

begun 1552, a fine structure, though

inferior in scale and detail to

its original.

Besides

these and other important

churches there were many

large domical chapels

of

great

splendor added to earlier

churches; of these the Chapel

of Sixtus V. in S.

M.

Maggiore,

at Rome, by D.

Fontana (15431607),

is an excellent example.

PALACES:

ROME. The

palaces on the Capitoline Hill, built at

different dates (1540

1644)

from designs by Michael Angelo,

illustrate the palace architecture of

this

period,

and the imposing effect of a single

colossal order running through two

stories.

This

treatment, though well adapted to produce

monumental effects in large

squares,

was

dangerous in its bareness and

heaviness of scale, and was

better suited for

buildings

of vast dimensions than for ordinary

street-façades. In other Roman

palaces

of

this time the traditions of the preceding

period still prevailed, as in the

Sapienza

(University),

by della Porta (1575), which has a

dignified court and a façade of

great

refinement

without columns or pilasters. The

Papal

palaces built by

Domenico

Fontana

on the Lateran, Quirinal, and Vatican

hills, between 1574 and 1590,

externally

copying the style of the Farnese, show a

similar return to earlier

models,

but

are less pure and refined in

detail than the Sapienza. The great

pentagonal Palace

of

Caprarola,

near Rome, by Vignola, is

perhaps the most successful and

imposing

production

of the Roman classic

school.

VERONA.

Outside

of Rome, palace-building took on

various local and

provincial

phases

of style, of which the most important

were the closely related

styles of

Verona,

Venice, and Vicenza. Michele

Sammichele (14841549),

who built in Verona

the

Bevilacqua,

Canossa,

Pompei, and

Verzi

palaces

and the four chief city gates,

and

in Venice the P.

Grimani,

his masterpiece (1550), was a

designer of great

originality

and power. He introduced into his

military architecture, as in the gates

of

Verona,

the use of rusticated orders, which he

treated with skill and taste. The

idea

was

copied by later architects and

applied, with doubtful propriety, to

palace-

façades;

though Ammanati's garden-façade for the

Pitti palace, in Florence

(cir.

1560),

is an impressive and successful

design.

VENICE.

Into the

development of the maturing classic

style Giacopo

Tatti Sansovino

(14771570)

introduced in his Venetian

buildings new elements of

splendor.

Coupled

columns between arches

themselves supported on columns, and a

profusion

of

figure sculpture, gave to

his palace-façades a hitherto unknown

magnificence of

effect,

as in the Library

of St. Mark (now the

Royal Palace, Fig. 172), and

the

Cornaro

palace

(P. Corner de Cà Grande), both

dating from about 153040. So

strongly

did he impress upon Venice these

ornate and sumptuous variations

on

classic

themes, that later architects

adhered, in a very debased period, to the

main

features

and spirit of his work.

FIG.

172.--LIBRARY OF ST. MARK,

VENICE.

VICENZA.

Of

Palladio's

churches

in Venice we have already

spoken; his palaces

are

mainly

to be found in his native city, Vicenza.

In these structures he displayed

great

fertility

of invention and a profound familiarity

with the classic orders, but the

degenerate

taste of the Baroque period

already begins to show itself in

his work.

There

is far less of architectural propriety

and grace in these pretentious

palaces,

with

their colossal orders and their

affectation of grandeur, than in the

designs of

Vignola

or Sammichele. Wood and plaster,

used to mimic stone,

indicate the

approaching

reign of sham in all design

(P.

Barbarano, 1570;

Chieregati,

1560;

Tiene,

Valmarano, 1556;

Villa

Capra). His

masterpiece is the two-storied

arcade

about

the mediæval Basilica, in which the

arches are supported on a minor

order

between

engaged columns serving as

buttresses. This treatment

has in consequence

ever

since been known as the Palladian

Motive.

GENOA.

During the

second half of the sixteenth century a

remarkable series of

palaces

was erected in Genoa,

especially notable for their great

courts and imposing

staircases.

These last were given

unusual prominence owing to differences

of level in

the

courts, arising from the slope of their

sites on the hillside. Many of these

palaces

were

by Galeazzo Alessi (150272); others

by architects of lesser note; but

nearly all

characterized

by their effective planning,

fine stairs and loggias, and

strong and

dignified,

if sometimes uninteresting, detail

(P.

Balbi,

Brignole,

Cambiasi,

Doria-

Tursi

[or

Municipio], Durazzo

[or

Reale], Pallavicini, and

University).

FIG.

173.--INTERIOR OF SAN SEVERO,

NAPLES.

THE

BAROQUE STYLE. A

reaction from the cold classicismo

of the

late sixteenth

century

showed itself in the following

period, in the lawless and vulgar

extravagances

of

the so-called Baroque

style.

The wealthy Jesuit order was a

notorious contributor

to

the debasement of architectural taste.

Most of the Jesuit churches and

many

others

not belonging to the order, but following

its pernicious example,

are

monuments

of bad taste and pretentious

sham. Broken and contorted

pediments,

huge

scrolls, heavy mouldings,

ill-applied sculpture in exaggerated

attitudes, and a

general

disregard for architectural propriety

characterized this period, especially

in

its

church architecture, to whose style the

name Jesuit

is

often applied. Sham

marble

and

heavy and excessive gilding

were universal (Fig. 173).

C.

Maderna (1556

1629),

Lorenzo

Bernini (15891680),

and F.

Borromini (15991667)

were the

worst

offenders of the period, though Bernini

was an artist of undoubted

ability, as

proved

by his colonnades or atrium in front of

St. Peter's. There were,

however,

architects

of purer taste whose works

even in that debased age were worthy

of

admiration.

FIG.

174.--CHURCH OF S. M. DELLA SALUTE,

VENICE.

BAROQUE

CHURCHES. The

Baroque style prevailed in church

architecture for

almost

two centuries. The majority of the

churches present varieties of the

cruciform

plan

crowned by a high dome which is usually

the best part of the design.

Everywhere

else the vices of the period

appear in these churches,

especially in their

façades

and internal decoration. S.

M. della Vittoria, by

Maderna, and Sta.

Agnese,

by

Borromini, both at Rome, are

examples of the style. Naples is

particularly full of

Baroque

churches (Fig. 173), a few of which, like

the Gesù

Nuovo (1584),

are

dignified

and creditable designs. The domical

church of S.

M. della Salute, at

Venice

(1631),

by Longhena, is also a majestic

edifice in excellent style

(Fig. 174), and here

and

there other churches offer

exceptions to the prevalent baseness of

architecture.

Particularly

objectionable was the wholesale

disfigurement of existing monuments

by

ruthless

remodelling, as in S. John Lateran, at

Rome, the cathedrals of Ferrara

and

Ravenna,

and many others.

PALACES.

These

were generally superior to the

churches, and not infrequently

impressive

and dignified structures. The two best

examples in Rome are

the

P.

Borghese, by

Martino

Lunghi the Elder (1590), with a

fine court arcade on

coupled

Doric and Ionic columns, and the

P.

Barberini, by

Maderna and Borromini,

with

an elliptical staircase by Bernini,

one of the few palaces in Italy with

projecting

lateral

wings. In Venice, Longhena, in the

Rezzonico

and

Pesaro

palaces

(165080),

showed

his freedom from the mannerisms of the

age by reproducing successfully

the

ornate

but dignified style of Sansovino. At

Naples D. Fontana, whose

works overlap

the

Baroque period, produced in the

Royal

Palace (1600) and the

Royal

Museum

(15861615)

designs of considerable dignity, in some

respects superior to his

papal

residences

in Rome. In suburban villas,

like the Albani

and

Borghese

villas

near

Rome,

the ostentatious style of the Decline

found free and congenial

expression.

LATER

MONUMENTS. In the few

eighteenth-century buildings which are

worthy of

mention

there is noticeable a reaction from the

extravagances of the seventeenth

century,

shown in the dignified correctness of the

exteriors and the somewhat

frigid

splendor

of the interiors. The most notable work

of this period is the Royal

Palace at

Caserta, by

Van

Vitelli (1752), an

architect of considerable taste and

inventiveness,

considering

his time. This great

palace, 800 feet square,

encloses four fine

courts,

and

is especially remarkable for the simple

if monotonous dignity of the well

proportioned

exterior and the effective planning of

its three octagonal

vestibules, its

ornate

chapel and noble staircase.

Staircases, indeed, were

among the most

successful

features of late Italian

architecture, as in the Scala

Regia of the

Vatican,

and

in the Corsini, Braschi, and Barberini

palaces at Rome, the Royal

Palace at

Naples,

etc.

In

church architecture the east

front of

S.

John Lateran in

Rome, by Galilei

(1734),

and

the whole exterior

of

S.

M. Maggiore, by

Ferd.

Fuga (1743),

are noteworthy

designs:

the former an especially powerful

conception, combining a colossal

order

with

two smaller orders in superposed

loggie, but

marred by the excessive scale of

the

statues

which crown it. The Fountain

of

Trevi,

conceived in much the same

spirit

(1735,

by Niccola

Salvi), is a

striking piece of decorative

architecture. The Sacristy of

St.

Peter's, by Marchionne

(1775),

also deserves mention as a

monumental and not

uninteresting

work. In the early years of the present

century the Braccio

Nuovo of

the

Vatican, by Stern, the

imposing church of S.

Francesco di Paola at

Naples, by

Bianchi,

designed in partial imitation of the

Pantheon, and the great S.

Carlo Theatre

at

Naples, show the same coldly

classical spirit, not wholly without

merit, but

lacking

in true originality and freedom of

conception.

CAMPANILES.

The

campaniles

of the

Renaissance and Decline deserve at

least

passing

reference, though they are neither

numerous nor often of

conspicuous

interest.

That of the Campidoglio

(Capitol)

at Rome, by Martino Lunghi, is a

good

example

of the classical type. Venetia

possesses a number of graceful and lofty

bell-

towers,

generally of brick with marble

bell-stages, of which the upper part of

the

Campanile

of

St.

Mark and the

tower of S. Giorgio Maggiore

are the finest

examples.

The

Decline attained what the early

Renaissance aimed at--the revival of

Roman

forms.

But it was no longer a Renaissance; it

was a decrepit and unimaginative

art,

held

in the fetters of a servile imitation,

copying the letter rather than the

spirit of

antique

design. It was the mistaken and

abject worship of precedent which

started

architecture

upon its downward path and led to the

atrocious products of the

seventeenth

century.

MONUMENTS

(mainly

in addition to those mentioned in

the text). 15TH CENTURY--

FLORENCE:

Foundling Hospital (Innocenti), 1421; Old

Sacristy and Cloister S.

Lorenzo;

P.

Quaratesi, 1440; cloisters at Sta.

Croce and Certosa, all by

Brunelleschi; façade S. M.

Novella,

by Alberti, 1456; Badia at Fiesole,

from designs of Brunelleschi, 1462;

Court of

P.

Vecchio, by Michelozzi, 1464 (altered

and enriched, 1565); P.

Guadagni, by Cronaca,

1490;

Hall of 500 in P. Vecchio, by same,

1495.--VENICE: S. Zaccaria, by

Martino

Lombardo,

14571515; S. Michele, by Moro Lombardo, 1466; S.

M. del Orto, 1473;

S.

Giovanni Crisostomo, by Moro Lombardo,

atrium of S. Giovanni

Evangelista,

Procurazie

Vecchie, all 1481; Scuola di S.

Marco, by Martino Lombardo, 1490; P.

Dario;

P.

Corner-Spinelli.--FERRARA: P. Schifanoja, 1469; P. Scrofa or

Costabili, 1485; S. M. in

Vado,

P. dei Diamanti, P. Bevilacqua, S.

Francesco, S. Benedetto, S. Cristoforo,

all 1490

1500.--MILAN:

Ospedale Grande (or

Maggiore), begun 1457 by Filarete,

extended by

Bramante,

cir. 148090 (great court by

Richini, 17th century); S. M. delle

Grazie,

E.

end, Sacristy of S. Satiro, S. M.

presso S. Celso, all by

Bramante, 14771499.--ROME:

S.

Pietro in Montorio, 1472; S. M. del

Popolo, 1475?; Sistine

Chapel of Vatican, 1475;

S.

Agostino, 1483.--SIENNA: Loggia del Papa

and P. Nerucci, 1460; P. del

Governo,

14691500;

P. Spannocchi, 1470; Sta. Catarina, 1490,

by di Bastiano and

Federighi,

church

later by Peruzzi; Library in

cathedral by L. Marina, 1497; Oratory

of

S.

Bernardino, by Turrapili, 1496.--PIENZA:

Cathedral, Bishop's Palace

(Vescovado),

P.

Pubblico, all cir. 1460, by B. di

Lorenzo (or Rosselini?).

ELSEWHERE (in

chronological

order):

Arch of Alphonso, Naples, 1443, by P. di

Martino; Oratory S.

Bernardino,

Perugia,

by di Duccio, 1461; Church over

Casa-Santa, Loreto, 14651526; P.

del

Consiglio

at Verona, by Fra Giocondo, 1476;

Capella Colleoni, Bergamo, 1476; S. M.

in

Organo,

Verona, 1481; Porta Capuana,

Naples, by Giul. da Majano, 1484;

Madonna

della

Croce, Crema, by B. Battagli,

14901556; Madonna di Campagna and S.

Sisto,

Piacenza,

both 14921511; P. Bevilacqua,

Bologna, by Nardi, 1492 (?); P.

Gravina,

Naples;

P. Fava, Bologna; P. Pretorio,

Lucca; S. M. dei Miracoli

Brescia; all at close

of

15th

century.

16TH CENTURY--ROME: P. Sora, 1501; S. M. della

Pace and cloister, 1504,

both by

Bramante

(façade of church by P. da Cortona, 17th

century); S. M. di Loreto, 1507,

by

A.

da San Gallo the Elder; P.

Vidoni, by Raphael; P. Lante, 1520;

Vigna Papa Giulio,

1534,

by Peruzzi; P. dei Conservatori, 1540,

and P. del Senatore, 1563

(both on

Capitol),

by M. Angelo, Vignola, and

della Porta; Sistine Chapel

in S. M. Maggiore, 1590;

S.

Andrea della Valle, 1591, by

Olivieri (façade, 1670, by

Rainaldi).--FLORENCE: Medici

Chapel

of S. Lorenzo, new sacristy of same,

and Laurentian Library, all

by M. Angelo,

152940;

Mercato Nuovo, 1547, by B. Tasso; P.

degli Uffizi, 156070, by

Vasari;

P.

Giugni, 15608.--VENICE: P. Camerlinghi, 1525, by Bergamasco;

S. Francesco della

Vigna,

by Sansovino, 1539, façade by Palladio,

1568; Zecca or Mint, 1536, and

VERONA:

Capella Pellegrini in S. Bernardino,

1514; City Gates, by Sammichele,

153040

(Porte

Nuova, Stuppa, S. Zeno, S.

Giorgio).--VICENZA: P. Porto, 1552; Teatro

Olimpico,

1580;

both by Palladio.--GENOA: P. Andrea Doria, by

Montorsoli, 1529; P. Ducale, by

Pennone,

1550; P. Lercari, P. Spinola, P. Sauli,

P. Marcello Durazzo, all by

Gal. Alessi,

cir.

1550; Sta. Annunziata, 1587, by della

Porta; Loggia dei Banchi,

end of 16th

century.--ELSEWHERE (in

chronological order). P. Roverella,

Ferrara, 1508; P. del

Magnifico,

Sienna, 1508, by Cozzarelli; P.

Communale, Brescia, 1508, by

Formentone;

P.

Albergati, Bologna, 1510; P. Ducale,

Mantua, 152040; P. Giustiniani,

Padua, by

Falconetto,

1524; Ospedale del Ceppo,

Pistoia, 1525; Madonna delle

Grazie, Pistoia, by

Vitoni,

1535; P. Buoncampagni-Ludovisi, Bologna, 1545;

Cathedral, Padua, 1550, by

Righetti

and della Valle, after M.

Angelo; P. Bernardini, 1560, and P.

Ducale, 1578, at

Lucca,

both by Ammanati.

17TH CENTURY:

Chapel of the Princes in S.

Lorenzo, Florence, 1604, by Nigetti; S.

Pietro,

Bologna,

1605; S. Andrea delle Fratte,

Rome, 1612; Villa Borghese,

Rome, 1616, by

Vasanzio;

P. Contarini delle Scrigni,

Venice, by Scamozzi; Badia at

Florence, rebuilt 1625

by

Segaloni; S. Ignazio, Rome, 162685;

Museum of the Capitol, Rome,

164450;

Church

of Gli Scalzi, Venice, 1649; P. Pesaro,

Venice, by Longhena, 1650; S.

Moisé,

Venice,

1668; Brera Palace, Milan; S. M.

Zobenigo, Venice, 1680; Dogana di

Mare,

Venice,

1686, by Benone; Santi Apostoli,

Rome.

18TH AND EARLY 19TH

CENTURY:

Gesuati, at Venice, 171530; S.

Geremia, Venice, 1753,

by

Corbellini; P. Braschi, Rome, by

Morelli, 1790; Nuova Fabbrica,

Venice, 1810.

24.

See

Appendix

C.

25.

See

Appendix

B.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.