|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

32

PRICING

AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.)

BROAD

CONTENTS

Organizational

Input Requirements

Labor

Distributions

Overhead

Costs

32.1

ORGANIZATIONAL

INPUT REQUIREMENTS:

Note

that once the work breakdown

structure and activity schedules are

established, the

program

manager calls a meeting for

all organizations that will

be required to submit

pricing

information.

It is imperative that all

pricing or labor-costing representatives be

present for the

first

meeting. During this

''kickoff" meeting, the work

breakdown structure is described in

depth

so

that each pricing unit

manager will know exactly

what his responsibilities

are during the

program.

The kickoff meeting also

resolves the struggle-for-power positions

of several

functional

managers whose responsibilities

may be similar to overlap on

certain activities. An

example

of this would be quality

control activities. During the

research and development

phase

of

a program, research personnel may be

permitted to perform their

own quality control

efforts,

whereas

during production activities the

quality control department or division

would have

overall

responsibility. Unfortunately, one

meeting is not always

sufficient to clarify

all

problems.

Follow-up or status meetings are

held, normally with only

those parties concerned

with

the problems that have arisen. Some

companies prefer to have all

members attend the

status

meetings so that all personnel will be

familiar with the total

effort and the

associated

problems.

The advantage of not having

all program-related personnel attend is

that time is of the

essence

when pricing out activities.

Many functional divisions

carry this policy one step

further

by

having a divisional representative

together with possibly key

department managers or section

supervisors

as the only attendees at the

kickoff meeting. The

divisional representative then

assumes

all responsibility for

assuring that all costing

data are submitted on time.

This

arrangement

may be beneficial in that the

program office need contact

only one individual

in

the

division to learn of the activity

status, but it may become a

bottleneck if the representative

fails

to maintain proper communication between

the functional units and the program

office, or

if

the individual simply is unfamiliar

with the pricing requirements of the work

breakdown

structure.

Time

may be extremely important,

during proposal activities.

There are many situations

in

which

a Request for Proposal (RFP) requires

that all responders submit

their bids no later than

a

specific

date, say within thirty

days. Under a proposal

environment, the activities of the

program

office, as well as those of the

functional units, are under

a schedule set forth by

the

proposal

manager. The proposal manager's

schedule has very little, if

any, flexibility and is

normally

under tight time constraints so

that the proposal may be

typed, edited, and

published

prior

to the date of submittal. In this

case, the Request for Proposal (RFP)

will indirectly

define

how

much time the pricing units

have to identify and justify labor

costs.

The

justification of the labor costs

may take longer than the

original cost estimates,

especially if

historical

standards are not available.

Many proposals often require

that comprehensive labor

justification

be submitted. Other proposals, especially

those that request an almost

immediate

response,

may permit vendors to submit

labor justification at a later

date.

Remember

that in the final analysis, it is the

responsibility of the lowest pricing

unit supervisors

to

maintain adequate standards, if possible,

so that an almost immediate response

can be given

to

a pricing request from a

program office.

232

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

32.2

LABOR

DISTRIBUTIONS:

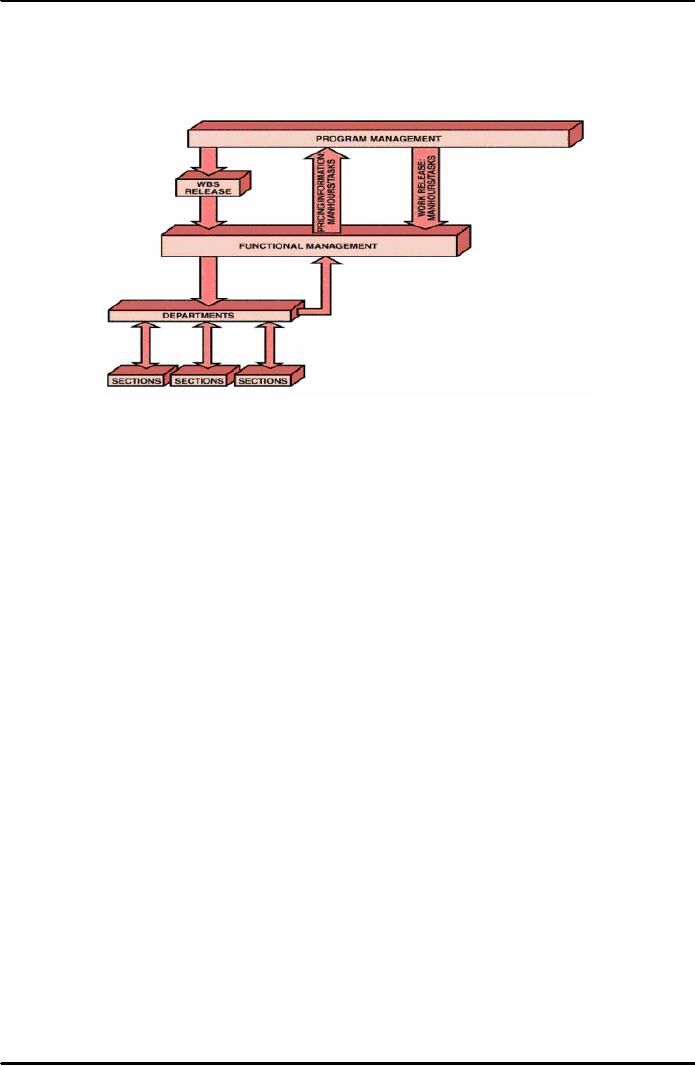

The

functional units supply

their input to the program

office in the form of man-hours as

shown

in

Figure 32.1 below.

Figure

32.1: Functional

Pricing Flow

The

input may be accompanied by

labor justification, if required.

The man-hours are

submitted

for

each task, assuming that the

task is the lowest pricing element,

and are time-phased per

month.

The man-hours per month per task

are converted to dollars

after multiplication by the

appropriate

labor rates. The labor

rates are generally known

with certainty over a

twelve-month

period,

but from then on are

only estimates. How can a

company predict salary structures

five

years

hence? If the company underestimates the salary

structure, increased costs and

decreased

profits

will occur. If the salary structure is overestimated,

the company may not be

competitive;

if

the project is government funded,

then the salary structure becomes an item

under contract

negotiations.

In

this regard, the development of the labor

rates to be used in the projection is

based on

historical

costs in business base hours and

dollars for the most recent

month or quarter.

Average

hourly

rates are determined for

each labor unit by direct

effort within the operations at

the

department

level. The rates are

only averages, and include

both the highest-paid employees

and

lowest-paid

employees, together with the department

manager and the clerical support.

These

base

rates are then escalated as

a percentage factor based on

past experience, budget as

approved

by management, and the local outlook

and similar industries. If the company

has a

predominant

aerospace or defense industry

business base, then these

salaries are negotiated

with

local

government agencies prior to

submittal for proposals.

The

labor hours submitted by the functional

units are quite often

overestimated for fear

that

management

will "massage" and reduce the

labor hours while attempting to

maintain the same

scope

of effort. Many times management is

forced to reduce man-hours either

because of

insufficient

funding or just to remain

competitive in the environment. The

reduction of man-

hours

often causes heated

discussions between the functional and

program managers. Program

managers

tend to think in terms of the

best interests of the program,

whereas functional

managers

lean toward maintaining

their present staff.

To

cater to this, the most common

solution to this conflict

rests with the program manager.

If

the

program manager selects

members for the program team

who are knowledgeable in

man-

hour

standards for each of the

departments, then an atmosphere of trust

can develop between the

program

office and the functional department so

that man-hours can be reduced in a

manner that

233

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

represents

the best interests of the company.

This is one of the reasons

why program team

members

are often promoted from

within the functional ranks.

The

man-hours submitted by the functional

units provide the basis for

total program cost

analysis

and program cost control. To

illustrate this process, consider the

following Example

32.1:

Example

32.1:

On

May 15, Apex Manufacturing decided to

enter into competitive bidding

for the modification

and

updating of an assembly line

program. A work breakdown structure

was developed as

shown

below:

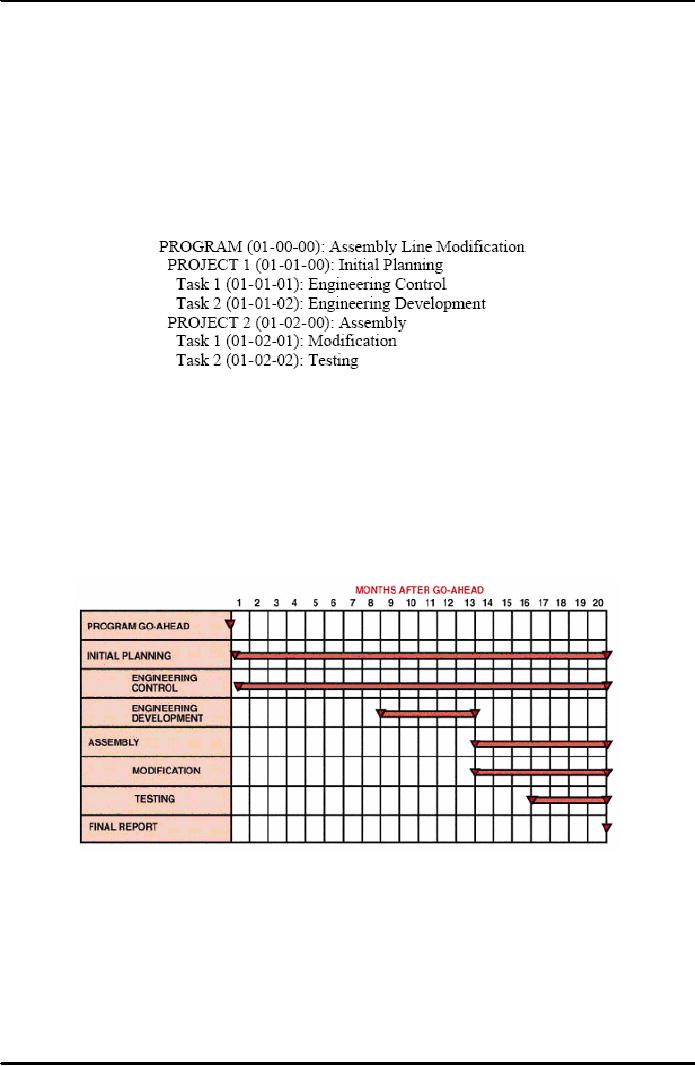

On

June 1, each pricing unit

was given the work breakdown

structure together with the

schedule

as

shown in Figure 32.2 below.

According to the schedule developed by

the proposal manager

for

this project, all labor

data must be submitted to

the program office for

review no later than

June

15. It should be noted here

that, in many companies,

labor hours are submitted

directly to

the

pricing department for submittal

into the base case computer

run. In this case, the

program

office

would "massage" the labor hours

only after the base case

figures are available.

This

procedure

assumes that sufficient time

exists for analysis and modification of

the base case. If

the

program office has

sufficient personnel capable of critiquing the

labor input prior to

submittal

to the base case, then

valuable time can be saved,

especially if two or three days

are

required

to obtain computer output for the

base case.

Figure

32.2: Activity

Schedule for Assembly Line

Updating

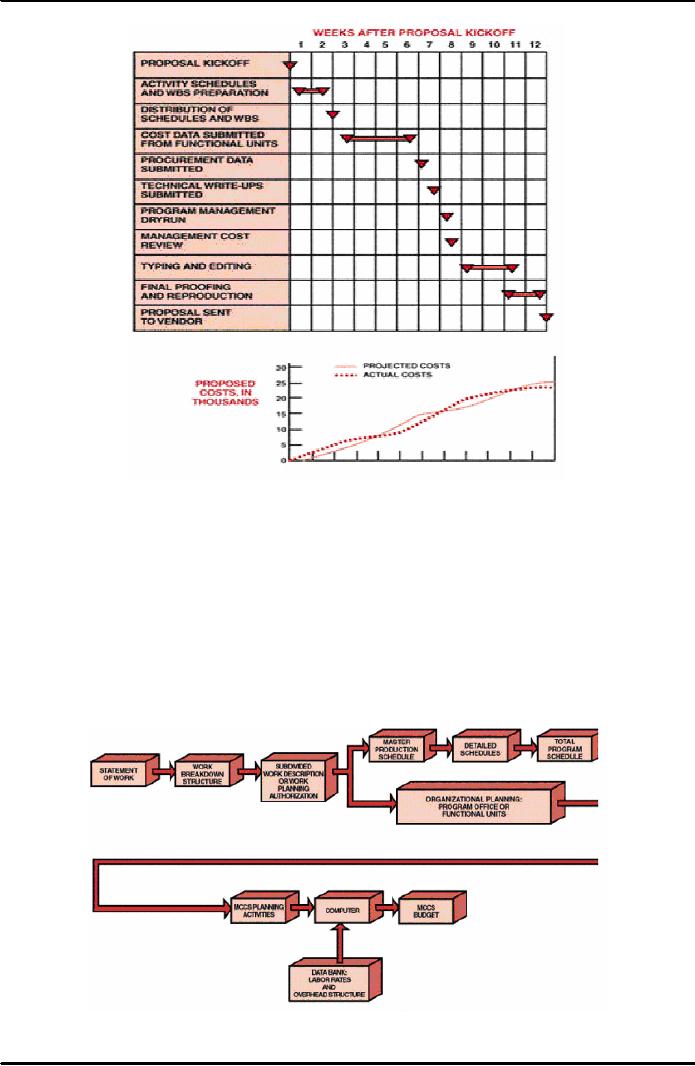

Note

that during proposal

activities, the proposal manager, pricing

manager, and program

manager

must all work together,

although the program manager

has the final say. The

primary

responsibility

of the proposal manager is to integrate

the proposal activities into the

operational

system

so that the proposal will be

submitted to the requestor on time. A

typical schedule

developed

by the proposal manager is shown in

Figure 32.3 below. The

schedule includes all

activities

necessary to "get the proposal

out of the house," with the

first major step being

the

submittal

of man-hours by the pricing organizations. It

also indicates the tracking of

proposal

costs.

The proposal activity

schedule is usually accompanied by a

time schedule with a

detailed

estimates

checklist if the complexity of the

proposal warrants one.

234

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

32.3: Proposal

Activity Schedule

The

checklist generally provides

detailed explanations for the

proposal activity

schedule.

After

the planning and pricing charts

are approved by program team

members and program

managers,

they are entered into an

Electronic Data Processing (EDP)

system as shown in Figure

32.4

below. The computer then

prices the hours on the planning charts

using the applicable

department

rates for preparation of the

direct budget time plan and

estimate-at-completion

reports.

The direct budget time

plan reports, once established, remain

the same for the life of

the

contract

except for customer directed or

approved changes or when

contractor management

determines

that a reduction in budget is

advisable. However, if a budget is

reduced by

management,

it cannot be increased without customer

approval.

Figure

32.4: Labor

Planning Flow Chart

235

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

In

addition, the time plan is

normally a monthly mechanical printout of

all planned effort by

work

package and organizational element over

the life of the contract, and serves as the

data

bank

for preparing the status

completion reports.

Initially,

the estimate-at-completion report is

identical to the budget report,

but it changes

throughout

the life of a program to reflect

degradation, or improvement in performance, or

any

other

events that will change the

program cost or

schedule.

32.3

OVERHEAD

RATES:

We

should know that the ability

to control program costs

involves more than tracking

labor

dollars

and labor hours. Overhead dollars can be

one of the biggest headaches in

controlling

program

costs and must be tracked along

with labor hours and dollars.

Although most

programs

have

an assistant program manager

for cost whose

responsibilities include monthly

overhead

rate

analysis, the program manager can

drastically increase the success of

his program by

insisting

that each program team

member understand overhead rates. For

example, if overhead

rates

apply only to the first

forty hours of work, then,

depending on the overhead rate,

program

dollars

can be saved by performing

work on overtime where the increased

salary is at a lower

burden.

This can be seen in Example

32.2 below.

Example

32.2:

Assume

that Apex Manufacturing must

write an interim report for

task 1 of project 1

during

regular

shift or on overtime. The

project will require 500

man-hours at $15.00 per hour.

The

overhead

burden is 75 percent on regular shift

but only 5 percent on overtime.

Overtime,

however,

is paid at a rate of time and a

half.

Assuming

that the report can be

written on either time,

which is cost-effective-- regular

time or

overtime?

·

On

regular time the total cost

is:

(500

hours) × ($15.00/hour) × (100% + 75%

burden) = $13,125

·

On

overtime, the total cost

is:

(500

hours) × ($15.00/hour × 1.5 overtime) ×

(100% + 5% burden) =

$11,812.50

Therefore,

the company can save $1,312.50 by

performing the work on overtime.

Scheduling

overtime

can produce increased profits if the

overtime overhead rate burden is

much less than

the

regular time burden. This

difference can be very large

in manufacturing divisions, where

overhead

rates between 300 and 450 percent

are common.

Regardless

of whether one analyzes a project or a

system, all costs must have

associated

overhead

rates. Unfortunately, many

program managers and systems

managers consider

overhead

rates as a magic number pulled out of the

air. The preparation and

assignment of

overheads

to each of the functional divisions is a

science. Although the total

dollar pool for

overhead

rates is relatively constant,

management retains the option of deciding

how to

distribute

the overhead among the functional divisions. A company

that supports its

Research

and

Development staff through

competitive bidding projects may

wish to keep the Research and

Development

overhead rate as low as possible. Care

must be taken, however, that

other

divisions

do not absorb additional

costs so that the company no longer

remains competitive on

those

manufactured products that may be its

bread and butter.

Furthermore,

the development of the overhead rates is a

function of three separate

elements:

direct

labor rates, direct business

base projections, and

projection of overhead expenses.

Direct

labor

rates have already been

discussed. The direct

business base projection

involves the

determination

of the anticipated direct labor hours

and dollars along with the

necessary direct

236

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

materials

and other direct costs

required to perform and complete the

program efforts

included

in

the business base. Those items

utilized in the business base

projection include all

contracted

programs

as well as the proposed or anticipated

efforts. The foundation for

determination of the

business

base required for each

program can be one or more of the

following:

·

Actual

costs to date and estimates to

completion

·

Proposal

data

·

Marketing

intelligence

·

Management

goals

·

Past

performance and trends

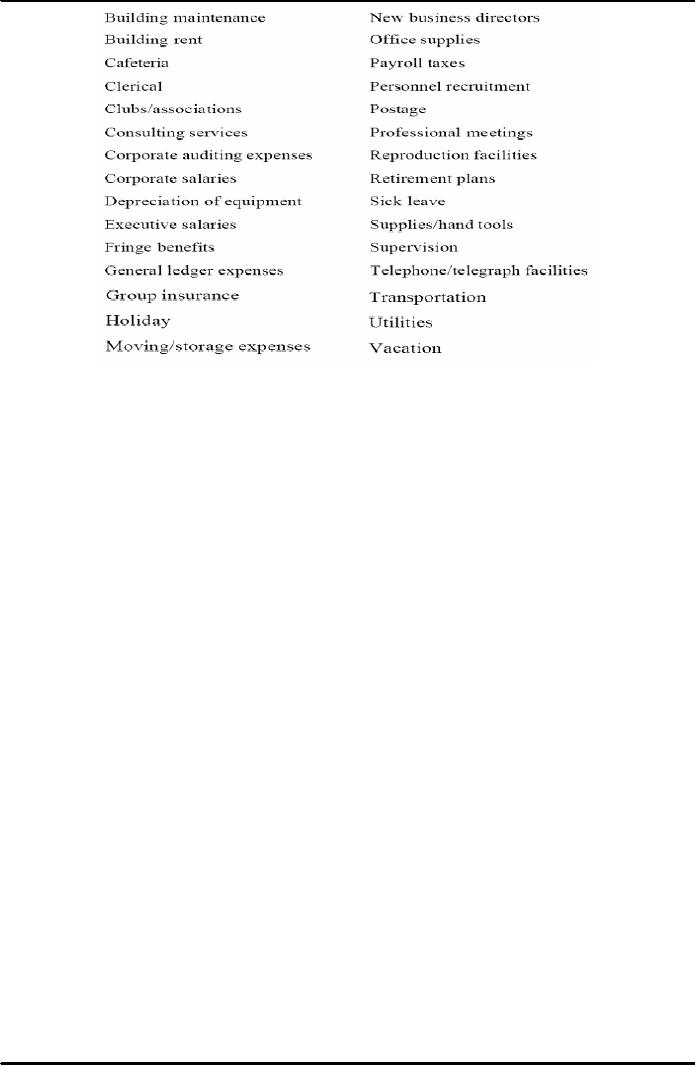

Additionally,

the projection of the overhead expenses is

made by an analysis of each of the

elements

that constitute the overhead expense. A

partial listing of those items

that constitute

overhead

expenses is shown in Table 32.1

below. Projection of expenses

within the individual

elements

is then made based on one or more of the

following:

·

Historical

direct/indirect labor

ratios

·

Regression

and correlation analysis

·

Manpower

requirements and turnover rates

·

Changes

in public laws

·

Anticipated

changes in company benefits

·

Fixed

costs in relation to capital

asset requirements

·

Changes

in business base

·

Bid

and proposal (B&P) tri-service

agreements

·

IR&D

tri-service agreements

In

case of many industries,

such as aerospace and

defense, the federal government

funds a large

percentage

of the Bid and proposal (B&P) and IR&D

activities. This federal

funding is a

necessity

since many companies could

not otherwise be competitive

within the industry.

The

federal

government employs this

technique to stimulate research and

competition. Therefore,

Bid

and proposal (B&P) and IR&D are

included in the above list.

The

annual budget is the prime

factor in the control of overhead costs.

This budget, which is

the

result

of goals and objectives established by the chief

executive officer, is reviewed

and

approved

at all levels of management. It is

established at department level, and the

department

manager

has direct responsibility

for identifying and controlling

costs against the approved

plan.

The

departmental budgets are summarized, in

detail, for higher levels of

management. This

summarization

permits management, at these higher

organizational levels, to be aware of

the

authorized

indirect budget in their

area of responsibility.

237

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Table

32.1: Elements

of Overhead Rates

Monthly

reports are published indicating

current month and

year-to-date budget, actuals,

and

variances.

These reports are published

for each level of

management, and an analysis is

made

by

the budget department through

coordination and review with

management. Each directorate's

total

organization is then reviewed

with the budget analyst who

is assigned the overhead cost

responsibility.

A joint meeting is held with

the directors and the vice president and

general

manager,

at which time overhead performance is

reviewed.

238

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles