|

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

LESSON

27

MOOD

DISORDERS

Recap

Lecture No. 26

DIAGNOSIS

Unipolar

Disorders

·

The

unipolar disorders include two

specific types: major depressive disorder

and dysthymia.

·

In

order to meet the criteria for major

depressive disorder, a person must

experience at least

one

major

depressive episode in the absence of

any history of manic

episodes.

·

Dysthymia

differs

from major depression in terms of

both severity and

duration.

·

Dysthymia

represents a chronic mild depressive

condition that has been

present for many

years.

·

In

order to fulfill DSM-IV-TR criteria

for this disorder, the person must,

over a period of at least

2

years,

exhibit a depressed mood for

most of the day on more days

than not.

·

Two

or more of the following symptoms

must also be present for a

diagnosis of dysthymia:

1.

Poor appetite or

overeating

2.

Insomnia or hypersomnia

3.

Low energy or fatigue

4.

Low self-esteem

5.

Poor concentration or difficulty

making decisions

6.

Feelings of hopelessness

·

These

symptoms must not be absent

for more than 2 months at a time

during the 2-year

period.

·

If

at any time during the initial 2

years the person met criteria

for a major depressive episode,

the

diagnosis

would be major depression rather than

dysthymia.

·

As

in the case of major depressive disorder, the

presence of a manic episode

would rule out a

diagnosis

of dysthymia.

127

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

·

The

distinction between major depressive

disorder and dysthymia is somewhat

artificial because

both

sets of symptoms are

frequently seen in the same

person.

·

In

such cases, rather than

thinking of them as separate disorders,

it is more appropriate to consider

them

as two aspects of the same disorder,

which waxes and wanes

over time.

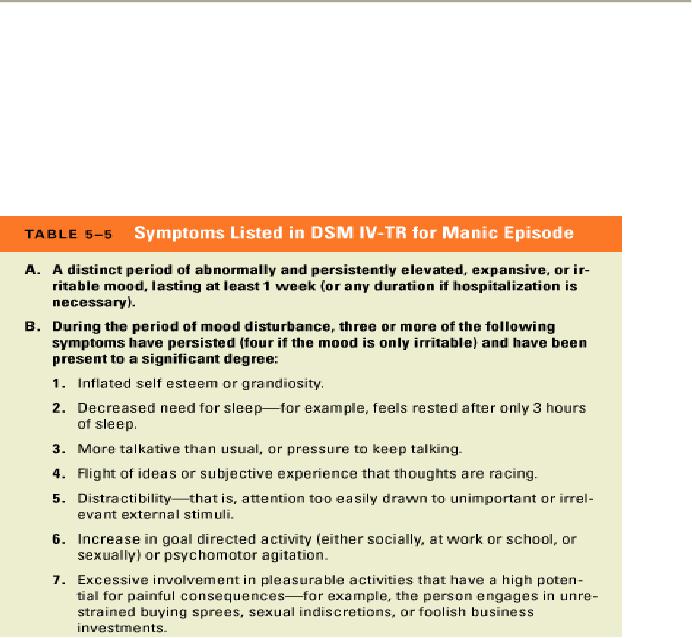

Bipolar

Disorders

·

All

three types of bipolar

disorders involve manic or hypomanic

episodes.

·

The

mood disturbance must be

severe enough to interfere with

occupational or social

functioning.

·

A

person who has experienced

at least one manic episode

would be assigned a diagnosis of

bipolar

I

disorder.

Bipolar

Disorders (continued)

·

Hypomania

refers

to episodes of increased energy

that are not sufficiently

severe to qualify as

full-

blown

mania.

·

A

person who has experienced

at least one major depressive

episode, at least one

hypomanic

episode,

and no full-blown manic

episodes would be assigned a

diagnosis of bipolar

II disorder.

·

The

differences between manic

and hypomanic episodes involve

duration and

severity.

·

The

symptoms need to be present

for a minimum of only 4 days

to meet the threshold for a

hypomanic

episode (as opposed to 1

week for a manic

episode).

·

The

mood change in a hypomanic episode

must be noticeable to others,

but the disturbance

must

not

be severe enough to impair social or

occupational functioning or to require

hospitalization.

·

Cyclothymia

is

considered by DSM-IV-TR to be a chronic

but less severe form of

bipolar

disorder.

·

In

order to meet criteria for

cyclothymia, the person must

experience numerous hypomanic

episodes

and numerous periods of

depression (or loss of

interest or pleasure) during a

period of 2

years.

128

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

·

There

must be no history of major depressive

episodes and no clear

evidence of a manic

episode

during

the first 2 years of the

disturbance.

Further

Descriptions and Subtypes

·

DSM-IV-TR

includes several additional

ways of describing subtypes of the

mood disorders.

·

These

are based on two

considerations:

1)

more specific descriptions of

symptoms that were present

during the most recent

episode

of

depression (known as episode

specifiers)

and

2)

more extensive descriptions of the

pattern that the disorder follows

over time (known as

course

specifiers).

·

One

episode specifier allows the clinician to

describe a major depressive episode as

having

melancholic

features.

·

Melancholia

is a term

that is used to describe a particularly

severe type of depression.

·

In

order to meet the DSM-IV-TR criteria

for melancholic features, a

depressed patient must

either

·

lose

the feeling of pleasure associated with

all, or almost all, activities or

·

Lose

the capacity to feel better--even

temporarily--when something good

happens.

·

The

person must also exhibit at

least three of the following to

meet the criteria of melancholia:

·

the

depressed mood feels

distinctly different from the

depression a person would feel after

the

death

of a loved one;

·

the

depression is most often worst in the

morning;

·

the

person awakens early, at

least 2 hours before

usual;

·

marked

psychomotor retardation or agitation;

·

significant

loss of appetite or weight loss;

and

·

excessive

or inappropriate guilt.

·

Another

episode specifier allows the clinician to

indicate the presence of psychotic

features--

hallucinations

or delusions--during the most recent

episode of depression or

mania.

·

Depressed

patients who exhibit

psychotic features are more

likely to require hospitalization

and

treatment

with a combination of antidepressant

and antipsychotic medication.

·

Another

episode specifier applies to

women who become depressed

or manic following

pregnancy.

·

A

major depressive or manic episode

can be specified as having a postpartum

onset if it

begins within

4

weeks after childbirth.

·

Because

the woman must meet the full

criteria for an episode of major

depression or mania, this

category

does not include minor

periods of postpartum "blues," which

are relatively common.

·

A

mood disorder (either unipolar or

bipolar) is described as following a

seasonal pattern if, over

a

period

of time, there is a regular relationship

between the onset of a person's

episodes and

particular

times of the year.

·

Researchers

refer to a mood disorder in which the

onset of episodes is regularly associated

with

changes

in seasons as seasonal

affective disorder.

·

Unipolar

Disorders

·

People

with unipolar mood disorders

typically have their first

episode in middle age; the

average

age

of onset is in the mid-forties.

·

DSM-IV-TR

sets the minimum duration at 2

weeks, but they can last

much longer.

·

In

one large-scale follow-up study, 10

percent of the patients had

depressive episodes that

lasted

more

than 2 years.

·

Most

unipolar patients will have

at least two depressive

episodes.

·

The

mean number of lifetime episodes is

five or six.

129

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

·

When

a person's symptoms are diminished or

improved, the disorder is considered to be

in

remission,

or a

period of recovery.

·

Relapse

is a

return of active symptoms in a

person who has recovered

from a previous episode.

·

Approximately

half of all unipolar

patients recover within 6 months of the

beginning of an episode.

·

The

probability that a patient

will recover from an episode

decreases after 6 months, and 10 to

20

percent

do not recover after 5

years.

·

Among

those who recover, 50 percent

relapse within 3

years.

Bipolar

Disorders

·

Onset

of bipolar mood disorders

usually occurs between the

ages of 28 and 33 years,

which is

younger

than the average age of

onset for unipolar

disorders.

·

The

first episode is just as

likely to be manic as

depressive.

·

The

average duration of a manic

episode runs between 2 and 3

months.

·

The

long-term course of bipolar

disorders is most often

episodic, and the prognosis is

mixed.

·

Most

patients have more than

one episode, and bipolar

patients tend to have more

episodes than

unipolar

patients.

·

Several

studies that have followed

bipolar patients over

periods of up to 10 years have

found that

40

to 50 percent of patients are

able to achieve a sustained

recovery from the disorder.

Incidence

and Prevalence

·

Unipolar

depression is one of the most common

forms of psychopathology.

·

Among

people who were interviewed for the

ECA study, approximately 6 percent were

suffering

from

a diagnosable mood disorder during a

period of 6 months.

·

The

ratio of unipolar to bipolar

disorders is at least

5:1.

·

Lifetime

risk for major depressive disorder was

approximately 5 percent, averaged across

sites in

the

ECA program.

·

The

lifetime risk for dysthymia

was approximately 3 percent and the

lifetime risk for bipolar

I

disorder

was close to 1

percent.

·

Almost

half the people who met

diagnostic criteria for dysthymia

had also experienced an

episode

of

major depression at some point in

their lives.

·

The

National Comorbidity Survey produced

even higher figures for the

lifetime prevalence of

mood

disorders; therefore the prevalence

estimates for mood disorders

in the ECA study are

probably

conservative.

·

Slightly

more than 30 percent of

those people in the ECA study

who met diagnostic criteria

for a

mood

disorder made contact with a

mental health professional during the 6

months prior to their

interview.

·

Gender

Differences

·

Women

are two or three times

more vulnerable to depression than

men are.

·

The

increased prevalence of depression

among women is apparently limited to

unipolar disorders.

·

Possible

explanations for this gender difference

have focused on a variety of factors,

including sex

hormones,

stressful life events, and

childhood adversity as well as

response styles that

are

associated

with gender roles.

·

Cross-Cultural

Differences

·

Comparisons

of emotional expression and

emotional disorder across cultural

boundaries encounter

a

number of methodological problems.

·

One

problem involves vocabulary.

130

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

·

Cross-cultural

differences have been

confirmed by a number of research

projects that have

examined

cultural variations in symptoms among

depressed patients in different

countries.

·

These

studies report comparable

overall frequencies of mood

disorders in various parts of

the

world,

but the specific type of symptom

expressed by the patients varies

from one culture to the

next.

·

In

Chinese patients, depression is

more likely to be described in

terms of somatic symptoms,

such

as

sleeping problems, headaches,

and loss of energy.

·

Depressed

patients in Europe and North

America are more likely to

express feelings of guilt

and

suicidal

ideas.

·

These

cross-cultural comparisons suggest that,

at its most basic level, clinical

depression is a

universal

phenomenon that is not limited to

Western or urban societies.

·

They

also indicate that a person's cultural

experiences, including linguistic,

educational, and

social

factors,

may play an important role in

shaping the manner in which he or

she expresses and

copes

with

the anguish of depression.

Risk

for Mood Disorders Across

the Life Span

·

Data

from the ECA project suggest

that mood disorders are

most frequent among young

and

middle-aged

adults.

·

Prevalence

rates for major depressive disorder

and dysthymia were significantly

lower for people

over

the age of 65.

·

The

frequency of bipolar disorders

was also low in the oldest

age groups.

·

The

frequency of depression is much higher

among certain subgroups of elderly

people.

·

The

prevalence of depression is particularly

high among those who

are about to enter

residential

care

facilities.

·

Elderly

people in nursing homes are more

likely to be depressed in comparison to a

random sample

of

elderly people living in the

community.

·

People

born after World War II seem

to be more likely to develop mood

disorders than were

people

from previous generations.

·

The

average age of onset for

clinical depression also seems to be

lower in people who were

born

more

recently; a pattern sometimes called a

birth cohort trend.

·

At

low levels and over

brief periods of time, depressed

mood may help us refocus

our motivations

and

it may help us to conserve

and redirect our energy in

response to experiences of loss

and

defeat.

·

A

disorder that is as common as depression

must have many causes rather

than one.

·

The

principle of equifinality, which holds

that there are many

ways to reach the same

outcome,

clearly

applies in the case of mood

disorders.

Social

Factors

·

The

experience of stressful life

events is associated with an

increased probability that a

person will

become

depressed.

·

Prospective

studies have found that

stressful life events are

useful in predicting the

subsequent

onset

of unipolar depression.

·

Although

many kinds of negative events

are associated with

depression, a special class

of

circumstances--those

involving major losses of important

people or roles--seem to play a crucial

role

in precipitating unipolar

depression.

·

Brown

and his colleagues believe

that depression is more

likely to occur when severe

life events are

associated

with feelings of humiliation, entrapment,

and defeat.

131

Abnormal

Psychology PSY404

VU

·

Variations

in the overall prevalence of depression

are driven in large part by

social factors that

influence

the frequency of stress in the

community.

Social

Factors and Bipolar Disorders

·

Some

studies have found that the

weeks preceding the onset of a

manic episode are marked by

an

increased

frequency of stressful life

events.

·

The

kinds of events that precede the

onset of mania tend to be

different from those that

lead to

depression.

·

While

the latter include primarily negative

experiences involving loss

and low self-esteem,

the

former

include schedule-disrupting events (such

as loss of sleep) as well as

goal attainment events.

·

Some

patients experience an increase in

manic symptoms after they have

achieved a significant goal

toward

which they had been

working.

·

Aversive

patterns of emotional expression

and communication within the family

can also have a

negative

impact on the adjustment of people with

bipolar mood

disorders.

·

Bipolar

patients who have less

social support are more

likely to relapse and

recover more slowly

than

patients with higher levels of

social support.

·

Stressful

life events can also

delay recovery from an

episode of depression in bipolar

patients.

·

The

course of bipolar mood disorder

can be influenced by the social

environment in which the

person

is living.

132

Table of Contents:

- ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY:PSYCHOSIS, Team approach in psychology

- WHAT IS ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR:Dysfunction, Distress, Danger

- PSYCHOPATHOLOGY IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT:Supernatural Model, Biological Model

- PSYCHOPATHOLOGY IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT:Free association, Dream analysis

- PSYCHOPATHOLOGY IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT:Humanistic Model, Classical Conditioning

- RESEARCH METHODS:To Read Research, To Evaluate Research, To increase marketability

- RESEARCH DESIGNS:Types of Variables, Confounding variables or extraneous

- EXPERIMENTAL REASEARCH DESIGNS:Control Groups, Placebo Control Groups

- GENETICS:Adoption Studies, Twin Studies, Sequential Design, Follow back studies

- RESEARCH ETHICS:Approval for the research project, Risk, Consent

- CAUSES OF ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR:Biological Dimensions

- THE STRUCTURE OF BRAIN:Peripheral Nervous System, Psychoanalytic Model

- CAUSES OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY:Biomedical Model, Humanistic model

- CAUSES OF ABNORMAL BEHAVIOR ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS OF ABNORMALITY

- CLASSIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT:Reliability, Test retest, Split Half

- DIAGNOSING PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS:The categorical approach, Prototypical approach

- EVALUATING SYSTEMS:Basic Issues in Assessment, Interviews

- ASSESSMENT of PERSONALITY:Advantages of MMPI-2, Intelligence Tests

- ASSESSMENT of PERSONALITY (2):Neuropsychological Tests, Biofeedback

- PSYCHOTHERAPY:Global Therapies, Individual therapy, Brief Historical Perspective

- PSYCHOTHERAPY:Problem based therapies, Gestalt therapy, Behavioral therapies

- PSYCHOTHERAPY:Ego Analysis, Psychodynamic Psychotherapy, Aversion Therapy

- PSYCHOTHERAPY:Humanistic Psychotherapy, Client-Centered Therapy, Gestalt therapy

- ANXIETY DISORDERS:THEORIES ABOUT ANXIETY DISORDERS

- ANXIETY DISORDERS:Social Phobias, Agoraphobia, Treating Phobias

- MOOD DISORDERS:Emotional Symptoms, Cognitive Symptoms, Bipolar Disorders

- MOOD DISORDERS:DIAGNOSIS, Further Descriptions and Subtypes, Social Factors

- SUICIDE:PRECIPITATING FACTORS IN SUICIDE, VIEWS ON SUICIDE

- STRESS:Stress as a Life Event, Coping, Optimism, Health Behavior

- STRESS:Psychophysiological Responses to Stress, Health Behavior

- ACUTE AND POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDERS

- DISSOCIATIVE AND SOMATOFORM DISORDERS:DISSOCIATIVE DISORDERS

- DISSOCIATIVE and SOMATOFORM DISORDERS:SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

- PERSONALITY DISORDERS:Causes of Personality Disorders, Motive

- PERSONALITY DISORDERS:Paranoid Personality, Schizoid Personality, The Diagnosis

- ALCOHOLISM AND SUBSTANCE RELATED DISORDERS:Poly Drug Use

- ALCOHOLISM AND SUBSTANCE RELATED DISORDERS:Integrated Systems

- SCHIZOPHRENIA:Prodromal Phase, Residual Phase, Negative symptoms

- SCHIZOPHRENIA:Related Psychotic Disorders, Causes of Schizophrenia

- DEMENTIA DELIRIUM AND AMNESTIC DISORDERS:DELIRIUM, Causes of Delirium

- DEMENTIA DELIRIUM AND AMNESTIC DISORDERS:Amnesia

- MENTAL RETARDATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

- MENTAL RETARDATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

- PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF CHILDHOOD:Kinds of Internalizing Disorders

- LIFE CYCLE TRANSITIONS AND ADULT DEVELOPMENT:Aging