|

LINE AND COLOUR OF COSTUMES IN HUNGARY |

| << SEX IN COSTUMING |

| STUDYING LINE AND COLOUR IN RUSSIA >> |

CHAPTER

XXI

LINE AND COLOUR OF

COSTUMES IN HUNGARY

HE

idea

that man decorative, by

reason of colour or line in

costume, is

of

necessity either masquerading or

effeminate, proceeds chiefly

from the

conventional

nineteenth and twentieth century

point of view in

America

and

western Europe. But even in

those parts of the world we

are

accustomed

to colour in the uniforms of

army and navy, the crimson

"hood" of the

university

doctor, and red sash of the

French Legion of Honour. We

accept colour

as

a dignified attribute of man's attire in

the cases cited, and we do

not forget that

our

early nineteenth century

American masculine forebears wore

bright blue or

vivid

green coats, silver and brass

buttons and red or yellow waistcoats.

The

gentleman

sportsman of the early

nineteenth century hunted in

bright blue tailed

coats

with brass buttons, scarlet

waistcoat, tight breeches

and top hat! We refer

to

the

same class of man who

to-day wears rough, natural

coloured tweeds, leather

coat

and close cap that his prey

may not see

him.

In

a sense, colour is a sign of

virility when used by man.

We have the North

American

Indian with his gay

feathers, blankets and war

paint, and the

European

peasant

in his gala costume. In many

cases colour is as much his

as his woman's.

Some

years ago, when collecting

data concerning national

characteristics as

expressed

in the art of the Slavs,

Magyars and Czechs, the writer

studied these

peoples

in their native settings. We

went first to Hungary and

were disappointed to

find

Buda Pest far too

cosmopolitan to be of value for

the study of national

costume,

music or drama. The

dominating and most artistic

element in Hungary is

the

Magyar, and we were there to

study him. But even

the Gypsies who played

the

Magyar

music in our hotel

orchestra, wore the black

evening dress of

western

Europe

and patent leather shoes, and

the music they played was

from the most

modern

operettas. It was not until a

world-famous Hungarian violinist

arrived to

give

concerts in Buda Pest that

the national spirit of the

Gypsies was stirred to

play

the

Magyar airs in his honour.

(Gypsies take on the spirit of

any adopted land). We

then

realised what they could make of

the Recockzy march and other

folk music.

The

experience of that evening spurred us to

penetrate into southern Hungary,

the

heart

of Magyar land, armed with

letters of introduction, from one of

the ministers

of

education, to mayors of the

peasant villages.

It

was impossible to get on without an

interpreter, as usually even

the mayors knew

only

the Magyar language--not a

word of German. That was the

perfect region for

getting

at Magyar character expressed in

the colour and line of

costume, manner of

living,

point of view, folk song and

dance. It is all still

vividly clear to our

mind's

eye.

We saw the first Magyar costumes in a

village not far from

Buda Pest. To

make

the few miles quickly, we

had taken an electric trolley,

vastly superior to

anything

in New York at the time of

which we speak; and were let

off in the centre

of

a group of small, low

thatched cottages, white-washed, and

having a broad band

of

one, two or three colours,

extending from the ground to

about three feet above

it,

and

completely encircling the

house. The favourite

combination seemed to be

blue

and

red, in parallel stripes. Near one of

these houses we saw a very

old woman with

a

long lashed whip in her

hand, guarding two or three

dark, curly,

long-legged

Hungarian

pigs. She wore high boots,

many short skirts, a shawl

and a head-

kerchief.

Presently two other figures

caught our eye: a man in a

long cape to the

tops

of his boots, made of sheepskin,

the wool inside, the

outside decorated

with

bright-coloured

wools, outlining crude designs.

The black fur collar was

the skin of

a

small black lamb, legs and

tail showing, as when

stripped off the little

animal.

The

man wore a cone-shaped hat of

black lamb and his hair

reached to his

shoulders.

He smoked a very long-stemmed pipe with a

china bowl, as he

strolled

along.

Behind him a woman walked,

bowed by the weight of an

immense sack. She

wore

boots to the knees, many full short

skirts, and a yellow and red silk

head-

kerchief.

By her head-covering we knew

her to be a married woman.

They were a

farmer

and his wife! Among

the Magyars the man is

very decidedly the

peacock;

the

woman is the pack-horse. On

market days he lounges in the

sunshine, wrapped

in

his long sheepskin cape, and smokes,

while she plies the trade.

In the farmers'

homes

of southern Hungary where we

passed some time, we, as

Americans, sat at

table

with the men of the house,

while wife and daughter

served. There was one

large

dish of food in the centre,

into which every one dipped!

The women of the

peasant

class never sit at table

with their men; they serve

them and eat

afterwards,

and

they always address them in

the second person as, "Will

your graciousness

have

a cup of coffee?" Also they

always walk behind the

men. At country

dances

we

have seen young girls in

bright, very full skirts,

with many ribbons braided

into

the

hair, cluster shyly at a

short distance from the

dancing platform in the

fair

grounds,

waiting to be beckoned or whistled to by one of

the sturdy youths

with

skin-tight

trousers, tucked into high

boots, who by right of might,

has stationed

himself

on the platform. When they

have danced, generally a czardas,

the girl goes

back

to the group of women,

leaving the man on the

platform in command of

the

situation!

Yet already in 1897 women were

being admitted to the

University of

Buda

Pest. There in Hungary one

could see woman run

the whole gamut of

her

development,

from man's slave to man's

equal.

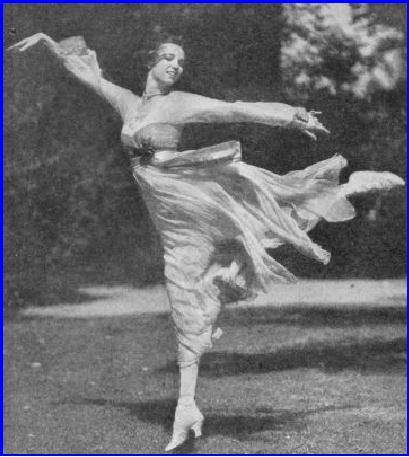

PLATE

XXVII

Mrs.

Vernon Castle in one of her

dancing

costumes.

She

was snapped by the camera as

she sprang

into

a pose of mere joyous abandon at

the

conclusion

of a long series of more or

less

exacting

poses.

Mrs.

Castle assures us that to repeat

the effect

produced

here, in which camera,

lucky

chance

and favourable wind combined,

would

be

well-nigh impossible.

Mrs.

Vernon Castle

A

Fantasy

We

found the national colour

scheme to have the same

violent contrasts

which

characterise

the folk music and the

folk poetry of the

Magyars.

Primitive

man has no use for

half-tones. It was the same

with the Russian

peasants

and

with the Poles. Our

first morning in Krakau a great

clattering of wheels and

horses'

hoofs on the cobbled court

of our hotel, accompanied by the

cracking of a

whip

and voices, drew us to our

window. At first we thought a

strolling circus had

arrived,

but no, that man

with the red crown to his

black fur cap, a peacock's

feather

fastened

to it by a fantastic brooch, was just an

ordinary farmer in Sunday

garb. In

the

neighbourhood of Krakau the

young men wear frock

coats of white cloth,

over

bright

red, short tight coats, and

their light-coloured skin-tight

trousers, worn inside

knee

boots, are embroidered in black down

the fronts.

One

afternoon we were the guests

of a Polish painter, who had

married a pretty

peasant,

his model. He was a gentleman by

birth and breeding, had

studied art in

Paris

and spoke French, German and

English. His wife, a child

of the soil, knew

only

the dialect of her own

province, but with the

sensitive response of a

Pole,

eagerly

waited to have translated to

her what the Americans

were saying of life

among

women in their country. She

served us with tea and liquor,

the red heels of

her

high boots clicking on the

wooden floor as she moved

about. As colour and as

line,

of a kind, that young Polish

woman was a feast to the eye; full

scarlet skirt,

standing

out over many petticoats and

reaching only to the tops of

her knee boots,

full

white bodice, a sleeveless jacket to the

waist line, made of brightly

coloured

cretonne,

outlined with coloured

beads; a bright yellow

head-kerchief bound

her

soft

brown hair; her eyes

were brown, and her skin

like a yellow peach. On

her

Table of Contents:

- A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES

- THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN

- HOW TO DRESS YOUR TYPE

- THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CLOTHES

- ESTABLISH HABITS OF CARRIAGE WHICH CREATE GOOD LINE

- COLOUR IN WOMAN'S COSTUME

- FOOTWEAR

- JEWELRY AS DECORATION

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER BOUDOIR

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER SUN-ROOM

- I. WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER GARDEN:WOMAN DECORATIVE ON THE LAWN

- WOMAN AS DECORATION WHEN SKATING

- WOMAN DECORATIVE IN HER MOTOR CAR

- HOW TO GO ABOUT PLANNING A PERIOD COSTUME

- I. THE STORY OF PERIOD COSTUMES:II. EGYPT AND ASSYRIA

- DEVELOPMENT OF GOTHIC COSTUME

- THE RENAISSANCE

- EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- WOMAN IN THE VICTORIAN PERIOD

- SEX IN COSTUMING

- LINE AND COLOUR OF COSTUMES IN HUNGARY

- STUDYING LINE AND COLOUR IN RUSSIA

- MARK TWAIN'S LOVE OF COLOUR IN ALL COSTUMING

- THE ARTIST AND HIS COSTUME

- IDIOSYNCRASIES IN COSTUME

- NATIONALITY IN COSTUME

- MODELS

- WOMAN COSTUMED FOR HER WAR JOB

- IN CONCLUSION