|

INTRODUCTION |

| PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS >> |

COLLEGE

HISTORIES OF ART

EDITED

BY

JOHN

C. VAN DYKE, L.H.D.

HISTORY

OF ARCHITECTURE

A.

D. F. HAMLIN

COLLEGE

HISTORIES OF ART

EDITED

BY

JOHN

C. VAN DYKE, L.H.D.

PROFESSOR OF THE HISTORY OF ART

IN

RUTGERS COLLEGE

HISTORY

OF PAINTING

By

JOHN C. VAN

DYKE,

the Editor of the Series. With

Frontispiece and 110

Illustrations,

Bibliographies, and Index. Crown 8vo,

HISTORY

OF ARCHITECTURE

By

ALFRED D. F. HAMLIN, A.M.

Adjunct Professor of Architecture,

Columbia College,

New

York. With Frontispiece and 229 Illustrations and

Diagrams, Bibliographies,

Glossary,

Index of Architects, and a General Index. Crown

8vo,

HISTORY

OF SCULPTURE

By

ALLAN MARQUAND,

Ph.D., L.H.D. and ARTHUR

L. FROTHINGHAM,

Jr., Ph.D.,

Professors

of Archæology and the History of Art in

Princeton University. With

Frontispiece

and 112 Illustrations. Crown 8vo,

THE

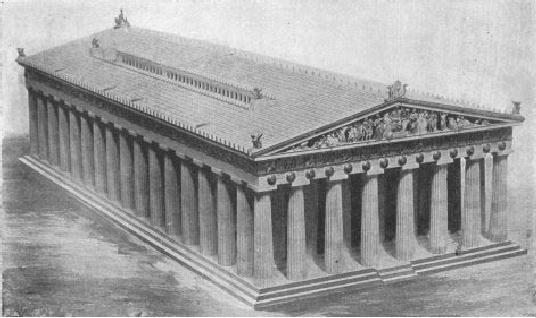

PARTHENON, ATHENS, AS RESTORED BY

CH. CHIPIEZ.

(From

model in Metropolitan Museum, New

York.)

A

TEXT-BOOK

OF

THE

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE

BY

A.

D. F. HAMLIN, A.M.

PROFESSOR

OF THE HISTORY OF

ARCHITECTURE

IN

THE SCHOOL OF

ARCHITECTURE,

COLUMBIA

UNIVERSITY

SEVENTH

EDITION

REVISED

L

O N G M A N S , G R E E N , A N D C O.

91

AND 93 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW

YORK

LONDON,

BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1909

PREFACE.

THE aim of this work has been to

sketch the various periods and

styles of

architecture

with the broadest possible strokes, and

to mention, with such

brief

characterization

as seemed permissible or necessary, the

most important works

of

each

period or style. Extreme

condensation in presenting the leading

facts of

architectural

history has been necessary,

and much that would rightly claim place

in

a

larger work has been omitted

here. The danger was felt to be

rather in the direction

of

too much detail than of too little.

While the book is intended

primarily to meet the

special

requirements of the college student,

those of the general reader

have not been

lost

sight of. The majority of the technical

terms used are defined or

explained in the

context,

and the small remainder in a glossary at

the end of the work. Extended

criticism

and minute description were out of the

question, and discussion of

controverted

points has been in

consequence as far as possible

avoided.

The

illustrations have been

carefully prepared with a view to

elucidating the text,

rather

than for pictorial effect. With the

exception of some fifteen

cuts reproduced

from

Lübke's Geschichte

der Architektur (by kind

permission of Messrs. Seemann,

of

Leipzig),

the illustrations are almost all

entirely new. A large number are from

vi

original

drawings made by myself, or under my

direction, and the remainder

are,

with

a few exceptions, half-tone reproductions

prepared specially for this work

from

photographs

in my possession. Acknowledgments are

due to Messrs. H. W.

Buemming,

H. D. Bultman, and A. E. Weidinger for valued

assistance in preparing

original

drawings; and to Professor W. R. Ware, to

Professor W. H. Thomson, M.D.,

and

to the Editor of the Series for much helpful

criticism and suggestion.

It

is hoped that the lists of monuments

appended to the history of each

period down

to

the present century may prove useful for

reference, both to the student and

the

general

reader, as a supplement to the body of

the text.

A.

D. F. HAMLIN.

Columbia

College, New York,

January

20, 1896.

The

author desires to express

his further acknowledgments to

the friends who have

at

various

times since the first

appearance of this book

called his attention to

errors in the text

or

illustrations, and to recent

advances in the art or in

its archæology deserving of

mention

in

subsequent editions. As far as

possible these suggestions

have been incorporated in

the

various

revisions and reprints which

have appeared since the

first publication.

A.

D. F. H.

Columbia

University,

October

28, 1907.

GENERAL

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

(This

includes the leading

architectural works treating of

more than one period or

style. The

reader

should consult also the

special references at the

head of each chapter.

Valuable

material

is also contained in the

leading architectural periodicals

and in monographs too

numerous

to mention.)

DICTIONARIES AND ENCYCLOPEDIAS.

Agincourt,

History

of Art by its Monuments;

London.

Architectural

Publication Society, Dictionary

of Architecture;

London.

Bosc,

Dictionnaire

raisonné d'architecture;

Paris.

Durm

and others, Handbuch

der Architektur;

Stuttgart. (This is an

encyclopedic

compendium

of architectural knowledge in many

volumes; the series not yet

complete.

It is referred to as the Hdbuch.

d. Arch.)

Gwilt,

Encyclopedia

of Architecture;

London.

Longfellow

and Frothingham, Cyclopedia

of Architecture in Italy and

the Levant;

New

York.

Planat,

Encyclopédie

d'architecture;

Paris.

Sturgis,

Dictionary

of Architecture and

Building; New

York.

GENERAL HANDBOOKS AND HISTORIES.

Bühlmann,

Die

Architektur des klassischen

Alterthums und der

Renaissance;

Stuttgart.

(Also

in English, published in New

York.)

Choisy,

Histoire

de l'architecture;

Paris.

Durand,

Recueil

et parallèle d'édifices de tous

genres;

Paris.

Fergusson,

History

of Architecture in All

Countries;

London.

Fletcher

and Fletcher, A

History of Architecture;

London.

Gailhabaud,

L'Architecture

du Vme. au XVIIIme.

siècle;

Paris.--Monuments

anciens et

modernes;

Paris.

Kugler,

Geschichte

der Baukunst;

Stuttgart.

Longfellow,

The

Column and the

Arch; New

York.

Lübke,

Geschichte

der Architektur;

Leipzig.--History

of Art, tr. and rev.

by R. Sturgis;

New

York.

Perry,

Chronology

of Mediæval and Renaissance

Architecture;

London.

Reynaud,

Traité

d'architecture;

Paris.

Rosengarten,

Handbook

of Architectural Styles;

London and New York.

Simpson,

A

History of Architectural

Development;

London.

Spiers,

Architecture

East and West;

London.

Stratham,

Architecture

for General Readers;

London.

Sturgis,

European

Architecture; New

York.

Transactions

of the Royal Institute of

British Architects;

London.

Viollet-le-Duc,

Discourses

on Architecture;

Boston.

THEORY,

THE

ORDERS,

ETC.

Chambers,

A

Treatise on Civil

Architecture;

London.

Daviler,

Cours

d'architecture de Vignole;

Paris.

Esquié,

Traité

élémentaire d'architecture;

Paris.

Guadet,

Théorie

de l'architecture;

Paris.

Robinson,

Principles

of Architectural Composition; New

York.

Ruskin,

The

Seven Lamps of

Architecture;

London.

Sturgis,

How

to Judge Architecture; New

York.

Tuckerman,

Vignola,

the Five Orders of

Architecture; New

York.

Van

Brunt, Greek

Lines and Other

Essays;

Boston.

Van

Pelt, A

Discussion of Composition.

Ware,

The

American Vignola;

Scranton.

HISTORY

OF ARCHITECTURE.

INTRODUCTION.

A

HISTORY of architecture is a record of

man's efforts to build beautifully.

The

erection

of structures devoid of beauty is

mere building, a trade and not an

art.

Edifices

in which strength and stability alone

are sought, and in designing which

only

utilitarian

considerations have been

followed, are properly works

of engineering.

Only

when the idea of beauty is added to that

of use does a structure take

its place

among

works of architecture. We may, then,

define architecture as the art

which

seeks

to harmonize in a building the

requirements of utility and of beauty. It is

the

most

useful of the fine arts and the

noblest of the useful arts. It

touches the life of

man

at every point. It is concerned not only in

sheltering his person and

ministering

to

his comfort, but also in

providing him with places for worship,

amusement, and

business;

with tombs, memorials, embellishments for

his cities, and other

structures

for

the varied needs of a complex

civilization. It engages the services of

a larger

portion

of the community and involves greater

outlays of money than any

other

occupation

except agriculture. Everyone at

some point comes in contact with

the

work

of the architect, and from this universal

contact architecture derives

its

significance

as an index of the civilization of an

age, a race, or a

people.

xxii

It

is the function of the historian of architecture to

trace the origin, growth, and

decline

of the architectural styles which have

prevailed in different lands and

ages,

and

to show how they have reflected the great

movements of civilization. The

migrations,

the conquests, the commercial, social,

and religious changes

among

different

peoples have all manifested

themselves in the changes of their

architecture,

and

it is the historian's function to show this. It is

also his function to explain

the

principles

of the styles, their characteristic forms

and decoration, and to describe

the

great

masterpieces of each style and

period.

STYLE

is a

quality; the "historic styles"

are phases of development.

Style

is

character

expressive

of definite conceptions, as of grandeur,

gaiety, or solemnity. An historic

style

is the

particular phase, the characteristic

manner of design, which prevails at

a

given

time and place. It is not the result of

mere accident or caprice, but

of

intellectual,

moral, social, religious, and

even political conditions.

Gothic architecture

could

never have been invented by

the Greeks, nor could the Egyptian

styles have

grown

up in Italy. Each style is based upon

some fundamental principle

springing

from

its surrounding civilization, which

undergoes successive developments until

it

either

reaches perfection or its

possibilities are exhausted,

after which a period of

decline

usually sets in. This is

followed either by a reaction and the

introduction of

some

radically new principle leading to the

evolution of a new style, or by the

final

decay

and extinction of the civilization and

its replacement by some

younger and

more

virile element. Thus the history of

architecture appears as a connected

chain of

causes

and effects succeeding each

other without break, each

style growing out of

that

which preceded it, or springing out of the

fecundating contact of a higher with

a

lower

civilization. To study architectural

styles is therefore to study a branch of

the

history

of civilization.

xxiii

Technically,

architectural styles are

identified by the means they employ to

cover

enclosed

spaces, by the characteristic forms of

the supports and other

members

(piers,

columns, arches, mouldings,

traceries, etc.), and by their

decoration. The plan

should

receive special attention,

since it shows the arrangement of the

points of

support,

and hence the nature of the structural

design. A comparison, for example,

of

the

plans of the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (Fig.

11, h)

and of the Basilica of

between

the two edifices, and hence a difference

of style.

STRUCTURAL

PRINCIPLES. All

architecture is based on one or

more of three

fundamental

structural principles; that of the

lintel, of the

arch

or

vault, and of

the

truss. The

principle of the lintel

is that of

resistance to transverse strains,

and

appears

in all construction in which a cross-piece or

beam rests on two or

more

vertical

supports. The arch

or

vault

makes

use of several pieces to

span an opening

between

two supports. These pieces

are in compression and exert

lateral pressures or

thrusts

which

are transmitted to the supports or

abutments. The thrust must be

resisted

either by the massiveness of the

abutments or by the opposition to it

of

counter-thrusts

from other arches or vaults.

Roman builders used the

first, Gothic

builders

the second of these means of

resistance. The truss

is a

framework so

composed

of several pieces of wood or

metal that each shall best

resist the particular

strain,

whether of tension or compression, to

which it is subjected, the whole

forming

a compound beam or arch. It is

especially applicable to very wide

spans, and

is

the most characteristic feature of

modern construction. How the adoption of

one or

another

of these principles affected the

forms and even the decoration of the

various

styles,

will be shown in the succeeding

chapters.

HISTORIC

DEVELOPMENT. Geographically

and chronologically, architecture

appears

to have originated in the Nile xxiv

valley. A second centre of

development is

found

in the valley of the Tigris and

Euphrates, not uninfluenced by the

older

Egyptian

art. Through various channels the Greeks

inherited from both Egyptian and

Assyrian

art, the two influences being discernible

even through the strongly

original

aspect

of Greek architecture. The Romans in

turn, adopting the external details

of

Greek

architecture, transformed its

substance by substituting the Etruscan

arch for

the

Greek construction of columns and

lintels. They developed a complete

and

original

system of construction and decoration and

spread it over the civilized

world,

which

has never wholly outgrown or

abandoned it.

With

the fall of Rome and the rise of

Constantinople these forms

underwent in the

East

another transformation, called the

Byzantine, in the development of

Christian

domical

church architecture. In the North and West,

meanwhile, under the growing

institutions

of the papacy and of the monastic orders

and the emergence of a feudal

civilization

out of the chaos of the Dark Ages, the

constant preoccupation of

architecture

was to evolve from the basilica type of

church a vaulted structure, and

to

adorn it throughout with an appropriate

dress of constructive and

symbolic

ornament.

Gothic architecture was the

outcome of this preoccupation, and

it

prevailed

throughout northern and western Europe

until nearly or quite the close

of

the

fifteenth century.

During

this fifteenth century the Renaissance

style matured in Italy, where it

speedily

triumphed

over Gothic fashions and

produced a marvellous series of

civic

monuments,

palaces, and churches, adorned with

forms borrowed or imitated

from

classic

Roman art. This influence

spread through Europe in the sixteenth

century,

and

ran a course of two centuries, after

which a period of servile classicism

was

followed

by a rapid decline in taste. To this

succeeded the eclecticism and

confusion

of

the nineteenth century, to xxv which the rapid growth

of new requirements and

development

of new resources have largely

contributed.

In

Eastern lands three

great schools of

architecture have grown

up

contemporaneously

with the above phases of Western art;

one under the influence of

Mohammedan

civilization, another in the Brahman and

Buddhist architecture of

India,

and the third in China and Japan. The

first of these is the richest and

most

important.

Primarily inspired from Byzantine art,

always stronger on the

decorative

than

on the constructive side, it has

given to the world the mosques and

palaces of

Northern

Africa, Moorish Spain,

Persia, Turkey, and India. The other two

schools

seem

to be wholly unrelated to the first, and

have no affinity with the architecture

of

Western

lands.

Of

Mexican, Central American, and

South American architecture so little is

known,

and

that little is so remote in history and

spirit from the styles above

enumerated,

that

it belongs rather to archæology than to

architectural history, and will not

be

considered

in this work.

NOTE.--The

reader's attention is called to

the Appendix to this volume,

in which are

gathered

some of the results of

recent investigations and of

the architectural progress of

the

last

few years which could not

readily be introduced into the

text of this edition.

The

General

Bibliography and the lists

of books recommended have

been revised and brought

up

to

date.

TABLE

OF CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I.

PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

II.

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

III.

EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE, Continued

CHAPTER

IV.

CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

V.

PERSIAN,

LYCIAN,

AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

VI.

GREEK ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

VII.

GREEK ARCHITECTURE,

Continued

CHAPTER

VIII.

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

IX.

ROMAN ARCHITECTURE,

Continued

CHAPTER

X.

EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

XI.

BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

XII.

SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE--ARABIAN,

MORESQUE,

PERSIAN,

INDIAN,

AND

TURKISH

CHAPTER

XIII.

EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY AND FRANCE

CHAPTER

XIV.

EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY,

GREAT

BRITAIN,

AND SPAIN

CHAPTER

XV.

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE

CHAPTER

XVI.

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE

ix

CHAPTER XVII.

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN

CHAPTER

XVIII.

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY,

THE

NETHERLANDS,

AND SPAIN

CHAPTER

XIX.

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY

CHAPTER

XX.

EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY

CHAPTER

XXI.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN

ITALY--THE

ADVANCED RENAISSANCE AND

DECLINE

CHAPTER

XXII.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE

CHAPTER

XXIII.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND

THE NETHERLANDS

CHAPTER

XXIV.

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY,

SPAIN,

AND PORTUGAL

CHAPTER

XXV.

THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE

x

CHAPTER XXVI.

RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN

EUROPE

CHAPTER

XXVII.

ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES

CHAPTER

XXVIII.

ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE--INDIA,

CHINA, AND

JAPAN

APPENDIX

GLOSSARY

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.