|

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER |

| << GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT |

| GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN >> |

CHAPTER

XVII.

GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT

BRITAIN.

BOOKS RECOMMENDED: As before, Corroyer,

Parker, Reber. Also, Bell's

Series of

Handbooks

of English Cathedrals.

Billings, The

Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities

of

Scotland.

Bond, Gothic

Architecture in England.

Brandon, Analysis

of Gothic

Architecture.

Britton, Cathedral

Antiquities of Great

Britain.

Ditchfield, The

Cathedrals

of

England. Murray,

Handbooks

of the English Cathedrals.

Parker, Introduction

to

Gothic

Architecture;

Glossary

of Architectural Terms;

Companion

to Glossary,

etc.

Rickman,

An

Attempt to Discriminate the

Styles of English

Architecture.

Sharpe,

Architectural

Parallels;

The

Seven Periods of English

Architecture. Van

Rensselaer,

English

Cathedrals.

Winkles and Moule, Cathedral

Churches of England and

Wales.

Willis,

Architectural

History of Canterbury

Cathedral; ditto

of

Winchester Cathedral;

Treatise

on Vaults.

GENERAL

CHARACTER. Gothic

architecture was developed in

England under a

strongly

established royal power, with an

episcopate in no sense hostile to the

abbots

or

in arms against the barons. Many of the

cathedrals had monastic chapters,

and

not

infrequently abbots were

invested with the episcopal rank.

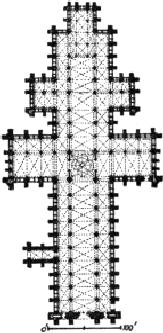

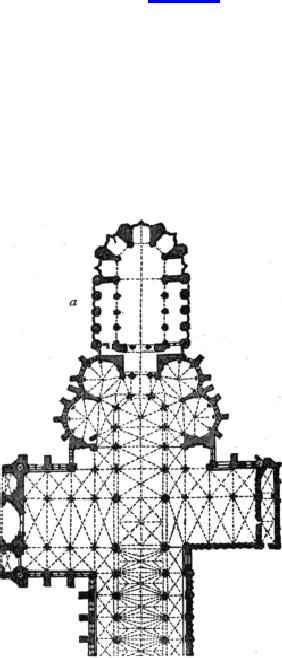

FIG.

128.--PLAN OF SALISBURY

CATHEDRAL.

English

Gothic architecture was thus by no

means predominantly an architecture

of

cathedrals.

If architectural activity in England

was on this account less

intense and

widespread

in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries than in

France, it was not, on the

other

hand, so soon exhausted. Fewer new

cathedrals were built, but the

progressive

rebuilding

of those already existing

seems not to have ceased until the

middle or end

of

the fifteenth century. Architecture in

England developed more slowly, but

more

uniformly

than in France. It contented itself with

simpler problems; and if it failed

to

rival

Amiens in boldness of construction and in

lofty majesty, it at least

never

perpetrated

a folly like Beauvais. In richness of

internal decoration, especially in

the

mouldings

and ribbed vaulting, and in the

picturesque grouping of simple

masses

externally,

the British builders went far toward

atoning for their structural

timidity.

EARLY

GOTHIC BUILDINGS. The

pointed arch and ribbed vault

were importations

from

France. Early examples

appear in the Cistercian abbeys of

Furness and Kirkstall,

and

in the Temple Church at London (1185).

But it was in the Choir

of Canterbury,

as

rebuilt by William of Sens,

after the destruction by fire in 1170 of

Anselm's

Norman

choir, that these French

Gothic features were first

applied in a

thoroughgoing

manner. In plan this choir resembled that

of the cathedral of Sens;

and

its coupled round piers, with

capitals carved with foliage,

its pointed arches,

its

six-part

vaulting, and its chevet,

were distinctly French. The

Gothic details thus

introduced

slowly supplanted the round arch and

other Norman features. For

fifty

years

the styles were more or less

mingled in many buildings, though

Lincoln

Cathedral, as

rebuilt in 11851200, retained

nothing of the earlier

round-arched

style.

But the first church to be designed and built from the

foundations in the new

style

was the cathedral of Salisbury

(12201258;

Fig. 128). Contemporary with

Amiens,

it is a homogeneous and typical example

of the Early English style.

The

predilection

for great length observable in the

Anglo-Norman churches (as at

Norwich

and

Durham) still prevailed, as it continued

to do throughout the Gothic

period;

Salisbury

is 480 feet long. The double

transepts, the long choir, the

square east end,

the

relatively low vault (84 feet to the

ridge), the narrow grouped windows, all

are

thoroughly

English. Only the simple four-part

vaulting recalls French

models.

Westminster

Abbey (12451269),

on the other hand, betrays in a marked

manner

the

French influence in its

internal loftiness (100 feet),

its polygonal chevet

and

MIXTURE

OF STYLES. Very few

English cathedrals are as

homogeneous as the two

just

mentioned, nearly all having

undergone repeated remodellings in

successive

periods.

Durham, Norwich, and Oxford are wholly Norman but for

their Gothic

vaults.

Ely, Rochester, Gloucester, and Hereford

have Norman naves and

Gothic

choirs.

Peterborough has an early

Gothic façade and late

Gothic retro-choir added

to

an

otherwise completely Norman structure.

Winchester is a Norman church

remodelled

with early Perpendicular details. The

purely Gothic churches and

cathedrals,

except parish churches--in which

England is very rich--are not nearly

as

numerous

in England as in France.

PERIODS.

The

development of English Gothic

architecture followed the same

general

sequence

as the French, and like it the successive

stages were most

conspicuously

characterized

by the forms of the tracery.

The

EARLY ENGLISH or

LANCET

period

extended roundly from 1175 or 1180 to 1280,

and

was marked by simplicity, dignity, and

purity of design.

The

DECORATED or GEOMETRIC period

covered another century, 1280 to 1380,

and

was

characterized by its decorative

richness and greater lightness of

construction.

The

PERPENDICULAR period extended

from 1380, or thereabout, well into the

sixteenth

century. Its salient features were the

use of fan-vaulting,

four-centred

arches,

and tracery of predominantly vertical and

horizontal lines. The tardy

introduction

of Renaissance forms finally put an end

to the Gothic style in

England,

after

a long period of mixed and

transitional architecture.

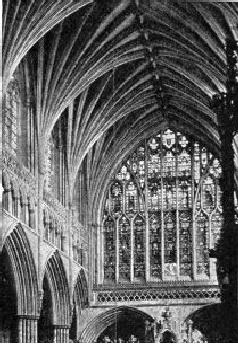

FIG.

129.--RIBBED VAULTING, CHOIR OF EXETER

CATHEDRAL.

VAULTING.

The

richness and variety of English

vaulting contrast strikingly with

the

persistent

uniformity of the French. A few of the early

Gothic vaults, as in the

aisles

of

Peterborough, and later the naves of

Durham, Salisbury, and Gloucester,

were

simple

four-part, ribbed vaults

substantially like the French. But the

English disliked

and

avoided the twisted and dome-like

surfaces of the French vaults,

preferring

horizontal

ridges, and, in the filling-masonry,

straight courses meeting at the

ridge in

zigzag

lines, as in southwest France.

This may be seen in Westminster

Abbey. The

idea

of ribbed construction was then

seized upon and given a new application.

By

springing

a large number of ribs from each point of

support, the vaulting-surfaces

were

divided into long, narrow, triangles, the

filling of which was comparatively

easy

(Fig.

129). The ridge was itself

furnished with a straight rib, decorated

with carved

rosettes

or bosses

at

each intersection with a vaulting-rib.

The naves and choirs of

Lincoln,

Lichfield, Exeter, and the nave of

Westminster illustrate this method.

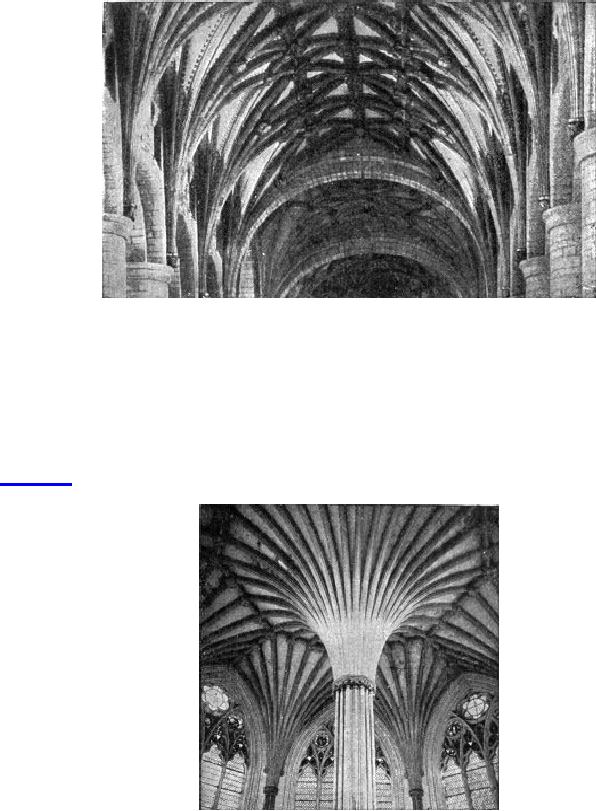

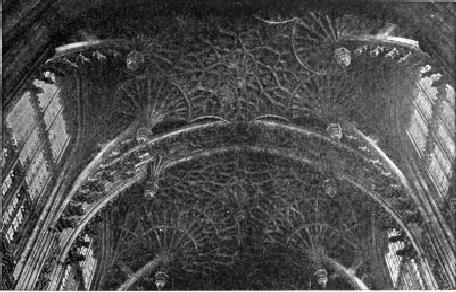

The

logical

corollary of this practice was the

introduction of minor ribs called

liernes,

connecting

the main ribs and forming complex

reticulated and star-shaped

patterns.

Vaults

of this description are among the

most beautiful in England. One of the

richest

is

in the choir of Gloucester (13371377).

Less correct constructively is that

over

the

choir of Wells, while the choir of Ely,

the nave of Tewkesbury Abbey

(Fig. 130),

and

all the vaulting of Winchester as rebuilt

by William of Wykeham (1390),

illustrate

the same system. Such vaults

are called lierne

or

star

vaults.

FIG.

130.--NET OR LIERNE VAULTING,

TEWKESBURY ABBEY.

FAN-VAULTING.

The next

step in the process may be observed in

the vaults of the

choir

of Oxford Cathedral (Christ Church), of

the retro-choir of Peterborough, of

the

cloisters

of Gloucester, and many other examples.

The diverging ribs being

made of

uniform

curvature, the severeys

(the

inverted pyramidal vaulting-masses

springing

from

each support) became a

species of concave conoids,

meeting at the ridge in

such

a

way as to leave a series of flat

lozenge-shaped spaces at the summit of the

vault

FIG.

131.--VAULT OF CHAPTER-HOUSE,

WELLS.

The

ribs were multiplied

indefinitely, and losing thus in

individual and structural

importance

became a mere decorative

pattern of tracery on the severeys. To

conceal

the

awkward flat lozenges at the ridge,

elaborate panelling was

resorted to; or, in

some

cases, long stone pendents

were inserted at those

points--a device highly

decorative

but wholly unconstructive. At Cambridge, in

King's

College Chapel,

at

Windsor,

in St.

George's Chapel, and in the

Chapel

of Henry VII. at

Westminster,

this

sort of vaulting received

its most elaborate

development. The fan-vault, as it

is

called,

illustrates the logical evolution of a

decorative element from a

structural

starting--point,

leading to results far removed from the

original conception. Rich

and

sumptuous

as are these ceilings, they

are with all their ornament

less satisfactory

than

the ribbed vaults of the preceding

period.

CHAPTER-HOUSES.

One of the

most beautiful forms of

ribbed vaulting was

developed

in the polygonal halls erected for the

deliberations of the cathedral

chapters

of Lincoln (1225), Westminster (1250),

Salisbury (1250), and Wells

(1292),

in which the vault-ribs radiated from a

central column to the sides and

angles

of the polygon (Fig. 131). If these

vaults were less majestic

than domes of the

same

diameter, they were far more

decorative and picturesque, while the

chapter-

houses

themselves were the most

original and striking products of

English Gothic art.

Every

feature was designed with

strict regard for the structural

system determined by

the

admirable vaulting, and the Sainte

Chapelle was not more

logical in its

exemplification

of Gothic principles. To the four

above-mentioned examples

should

be

added that of York (12801330), which differs from

them in having no central

column:

by some critics it is esteemed the

finest of them all. Its ceiling is a

Gothic

dome,

57 feet in diameter, but unfortunately

executed in wood. Its

geometrical

window-tracery

and richly canopied stalls are

admirable.

OCTAGON

AT ELY. The

magnificent Octagon

of Ely

Cathedral, at the intersection of

the

nave and transepts, belongs in the

same category with these

polygonal chapter-

house

vaults. It was built by Alan of

Walsingham in 1337, after the fall of

the

central

tower and the destruction of the adjacent

bays of the choir. It occupies

the

full

width of the three aisles, and covers the

ample space thus enclosed with a

simple

but

beautiful groined and ribbed vault of

wood reaching to a central

octagonal

lantern,

which rises much higher and shows

externally as well as internally.

Unfortunately,

this vault is of wood, and would require

important modifications of

detail

if carried out in stone. But it is so

noble in general design and

total effect, that

one

wonders the type was not

universally adopted for the crossing in

all cathedrals,

until

one observes that no cathedral of

importance was built after

Walsingham's

time,

nor did any other central towers

opportunely fall to the ground.

WINDOWS

AND TRACERY. In the

Early English Period (12001280 or

1300) the

windows

were tall and narrow (lancet

windows),

and generally grouped by twos and

threes,

though sometimes four and even five

are seen together (as the

"Five Sisters"

in

the N. transept of York). In the nave of

Salisbury and the retro-choir of Ely

the

side

aisles are lighted by

coupled windows and the clearstory by

triple windows, the

central

one higher than the others--a

surviving Norman practice. Plate-tracery

was,

as

in France, an intermediate step

leading to the development of bar-tracery

(see

Fig.

110).

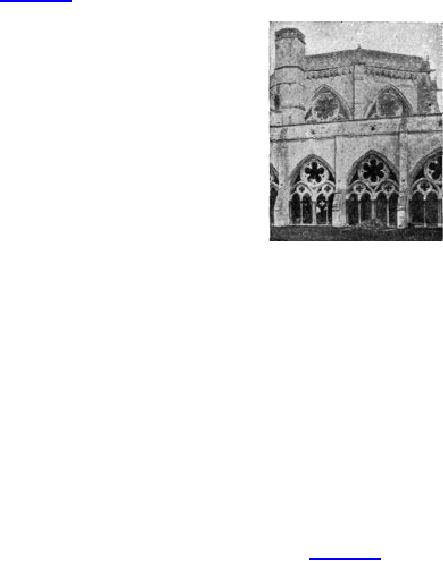

FIG.

132.--CLOISTERS, SALISBURY CATHEDRAL

(SHOWING UPPER PART OF

CHAPTER-HOUSE).

The

English followed here the

same reasoning as the French. At

first the openings

constituted

the design, the intervening stonework

being of secondary

importance.

Later

the forms of the openings were

subordinated to the pattern of the

stone

framework

of bars, arches, circles, and

cusps. Bar-tracery of this

description

prevailed

in England through the greater part of the

Decorated Period (12801380),

and

somewhat resembled the contemporary

French geometric tracery, though

more

varied

and less rigidly constructive in

design. An early example of this

tracery occurs

in

the cloisters of Salisbury (Fig. 132);

others in the clearstories of the choirs

of

Lichfield,

Lincoln, and Ely, the nave of York, and the

chapter-houses mentioned

above,

where, indeed, it seems to

have received its earliest

development. After the

middle

of the fourteenth century lines of double

curvature were

introduced,

producing

what is called flowing

tracery,

somewhat resembling the

French

Wells,

in the side aisles and triforium of the

choir of Ely, and in the S. transept

rose-

window

of Lincoln.

THE

PERPENDICULAR STYLE. Flowing

tracery was, however, a

transitional phase

of

design, and was soon

superseded by Perpendicular

tracery,

in which the mullions

were

carried through to the top of the arch and

intersected by horizontal

transoms.

This

formed a very rigid and mechanically

correct system of stone

framing, but

lacked

the grace and charm of the two preceding

periods. The earliest examples

are

seen

in the work of Edington and of Wykeham in the

reconstructed cathedral of

Winchester

(13601394), where the tracery was

thus made to harmonize with the

accentuated

and multiplied vertical lines of the

interior design. It was at this

late

date

that the English seem first to

have fully appropriated the Gothic

ideas of

emphasized

vertical elements and wall surfaces

reduced to a minimum. The

development

of fan-vaulting had led to the adoption

of a new form of arch, the four-

centred

or Tudor

arch (Fig.

133), to fit under the depressed apex of the vault.

The

whole

design internally and externally

was thenceforward controlled by the form

of

the

vaulting and of the openings. The windows

were made of enormous

size,

especially

at the east end of the choir, which

was square in nearly all

English

churches,

and in the west windows over the

entrance. These windows had

already

reached,

in the Decorated Period, an enormous

size, as at York; in the

Perpendicular

Period

the two ends of the church were as nearly

as possible converted into walls

of

glass.

The East Window of Gloucester reaches the

prodigious dimensions of 38 by 72

feet.

The most complete examples of the

Perpendicular tracery and of the style

in

general

are the three chapels

already mentioned; those, namely, of

King's

College at

Cambridge,

of St.

George at

Windsor, and of Henry

VII. in

Westminster Abbey.

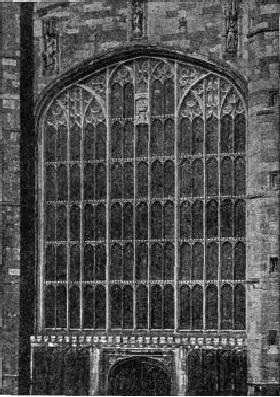

FIG.

133.--PERPENDICULAR TRACERY, WEST

WINDOW OF ST. GEORGE'S,

WINDSOR.

CONSTRUCTIVE

DESIGN. The

most striking peculiarity of

English Gothic design

was

its studious avoidance of

temerity or venturesomeness in

construction. Both the

height

and width of the nave were kept within

very moderate bounds, and the

supports

were never reduced to

extreme slenderness. While much

impressiveness of

effect

was undoubtedly lost

thereby, there was some

gain in freedom of design,

and

there

was less obtrusion of

constructive elements in the exterior

composition. The

flying-buttress

became a feature of minor importance

where the clearstory was

kept

low,

as in most English churches. In many

cases the flying arches were

hidden under

the

aisle roofs. The English

cathedrals and larger churches

are long and low,

depending

for effect mainly upon the projecting

masses of their transepts, the

imposing

square central towers which

commonly crown the crossing, and

the

grouping

of the main structure with chapter-houses,

cloisters, and Lady-chapels.

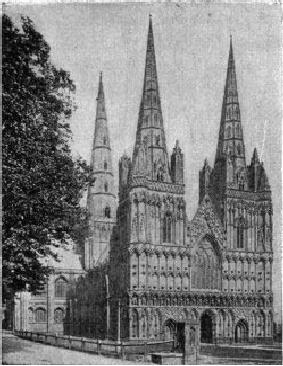

FIG.

134.--WEST FRONT, LICHFIELD

CATHEDRAL.

FRONTS.

The

sides and east ends were, in

most cases, more successful

than the

west

fronts. In these the English

displayed a singular indifference or

lack of creative

power.

They produced nothing to rival the

majestic façades of Notre

Dame, Amiens,

or

Reims, and their portals are

almost ridiculously small. The front of

York

Cathedral

is

the most notable in the list for

its size and elaborate

decoration. Those of Lincoln

and

Peterborough

are,

however, more interesting in the

picturesqueness and

singularity

of their composition. The first-named

forms a vast arcaded

screen,

masking

the bases of the two western towers, and

pierced by three huge

Norman

arches,

retained from the original façade. The

west front of Peterborough is

likewise

a

mask or screen, mainly composed of

three colossal recessed

arches, whose vast

scale

completely dwarfs the little porches

which give admittance to the

church.

Salisbury

has a curiously illogical and

ineffective façade. Those of

Lichfield

and

Wells

are,

on the other hand, imposing and beautiful

designs, the first with its

twin

spires

and rich arcading (Fig. 134), the second

with its unusual wealth of

figure-

sculpture,

and massive square

towers.

CENTRAL

TOWERS. These

are the most successful

features of English

exterior

design.

Most of them form lanterns internally

over the crossing, giving to that point

a

considerable

increase of dignity. Externally they are

usually massive and lofty

square

towers,

and having been for the most part

completed during the fourteenth

and

fifteenth

centuries they are marked by

great richness and elegance of

detail. Durham,

York,

Ely, Canterbury, Lincoln, and Gloucester

maybe mentioned as

notable

examples

of such square towers; that of

Canterbury is the finest. Two or three

have

lofty

spires over the lantern.

Among these, that of Salisbury is

chief, rising 424

feet

from

the ground, admirably designed in

every detail. It was not

completed till the

middle

of the fourteenth century, but most

fortunately carries out with great

felicity

the

spirit of the earlier style in which it

was begun. Lichfield and

Chichester have

somewhat

similar central spires, but

less happy in proportion and

detail than the

beautiful

Salisbury example.

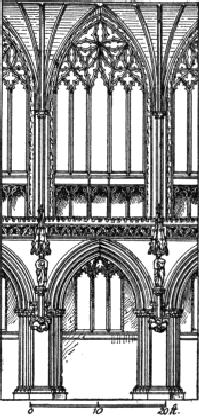

FIG.

135.--ONE BAY OF CHOIR, LICHFIELD

CATHEDRAL.

INTERIOR

DESIGN. In the Norman

churches the pier-arches, triforium,

and

clearstory

were practically equal. In the

Gothic churches the pier-arches

generally

occupy

the lower half of the height, the upper

half being divided nearly

equally

between

the triforium and clearstory, as in Lincoln,

Lichfield (nave), Ely (choir).

In

some

cases, however (as at

Salisbury, Westminster, Winchester,

choir of Lichfield),

the

clearstory is magnified at the expense of

the triforium (Fig. 135). Three

peculiarities

of design sharply distinguish the

English treatment of these

features

from

the French. The first is the multiplicity

of fine mouldings in the pier-arches;

the

second

is the decorative elaboration of design

in the triforium; the third, the variety

in

the treatment of the clearstory. In

general the English interiors

are much more

ornate

than the French. Black Purbeck

marble is frequently used for the

shafts

clustered

around the central core of the

pier, giving a striking and

somewhat singular

effect

of contrasted color. The rich vaulting,

the highly decorated triforium, the

moulded

pier-arches, and at the end of the vista

the great east window, produce

an

impression

very different from the more simple and

lofty stateliness of the French

cathedrals.

The great length and lowness of the

English interiors combine with

this

decorative

richness to give the impression of

repose and grace, rather than of

majesty

and

power. This tendency reached

its highest expression in the

Perpendicular

churches

and chapels, in which every surface

was covered with minute

panelling.

CARVING.

In the

Early English Period the

details were carved with a

combined

delicacy

and vigor deserving of the highest

praise. In the capitals and

corbels,

crockets

and finials, the foliage was

crisp and fine, curling into

convex masses and

seeming

to spring from the surface which it

decorated. Mouldings were

frequently

ornamented

with foliage of this character in the

hollows, and another ornament,

the

dog-tooth

or

pyramid,

often served the same

purpose, introducing repeated

points of

light

into the shadows of the mouldings. These

were fine and complex, deep

hollows

alternating

with round mouldings (bowtels)

sometimes made pear-shaped in

section

by

a fillet on one side.

Cusping--the

decoration of an arch or circle by

triangular

projections

on its inner edge--was introduced

during this period, and became

an

important

decorative resource, especially in

tracery design. In the Decorated

Period

the

foliage was less crisp;

sea-weed and oak-leaves, closely and

confusedly bunched,

were

used in the capitals, while crockets

were larger, double-curved, with

leaves

swelling

into convexities like oak-galls.

Geometrical and flowing tracery

were

developed,

and the mouldings of the tracery-bars, as of

other features, lost

somewhat

in

vigor and sharpness. The ball-flower

or button

replaced the dog's-tooth, and the

hollows

were less frequently adorned

with foliage.

In

the Perpendicular Period nearly all flat

surfaces were panelled in

designs

resembling

the tracery of the windows. The capitals

were less important than

those

of

the preceding periods, and the mouldings

weaker and less effective. The

Tudor

rose

appears as an ornament in square

panels and on flat surfaces; and

moulded

battlements,

which first appeared in Decorated work,

now become a frequent

crowning

motive in place of a cornice.

There is less originality and

variety in the

ornament,

but a great increase in its amount

(Fig. 136).

FIG.

136.--FAN-VAULTING, HENRY VII.'S

CHAPEL, WESTMINSTER

ABBEY.

PLANS.

English

church plans underwent, during the

Gothic Period, but little

change

from

the general types established

previous to the thirteenth century. The

Gothic

cathedrals

and abbeys, like the Norman, were very

long and narrow, with choirs

often

nearly as long as the nave, and

almost invariably with square

eastward

terminations.

There is no example of double

side aisles and side

chapels, and apsidal

chapels

are very rare. Canterbury and

Westminster (Fig. 137) are the

chief

exceptions

to this, and both show clearly the French

influence. Another

striking

peculiarity

of the English plans is the frequent

occurrence of secondary

transepts,

adding

greatly to the external picturesqueness.

These occur in rudimentary form

in

Canterbury,

and at Durham the Chapel of the Nine Altars,

added 12421290 to the

eastern

end, forms in reality a

secondary transept. This

feature is most

perfectly

Worcester,

Wells, and a few other examples. The

English cathedral plans are

also

distinguished

by the retention or incorporation of many

conventual features, such

as

cloisters,

libraries, and halls, and by the grouping

of chapter-houses and Lady-

chapels

with the main edifice. Thus the English

cathedral plans and those of

the

great

abbey churches present a

marked contrast with those of

France and the

Continent

generally. While Amiens, the

greatest of French cathedrals, is 521

feet

long,

and internally 140 feet high, Ely

measures 565 feet in length, and

less than 75

feet

in height. Notre Dame is 148

feet wide; the English naves

are usually under 80

feet

in total width of the three

aisles.

FIG.

137.--EASTERN HALF OF WESTMINSTER

ABBEY. PLAN.

a,

Henry VII.'s

chapel.

PARISH

CHURCHES. Many of

these were of exceptional

beauty of composition and

detail.

They display the greatest variety of

plan, churches with two

equal-gabled

naves

side by side being not

uncommon. A considerable proportion of

them date

from

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries,

and are chiefly interesting for

their

square,

single, west towers and their

carved wooden ceilings (see

below). The tower

was

usually built over the central

western porch; broad and

square, with corner

buttresses

terminating in pinnacles, it was

usually finished without spires.

Crenelated

battlements

crowned the upper story. When spires

were added the transition

from

the

square tower to the octagonal

spire was effected by

broaches

or

portions of a

square

pyramid intersecting the base of the

spire, or by corner pinnacles and

flying-

buttresses.

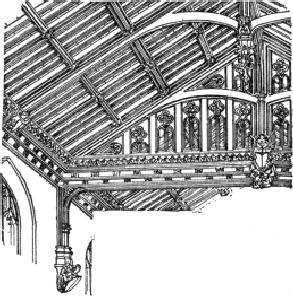

FIG.

138.--ROOF OF NAVE, ST.

MARY'S, WESTONZOYLAND.

WOODEN

CEILINGS. The

English treated woodwork with

consummate skill. They

invented

and developed a variety of forms of

roof-truss in which the proper

distribution

of the strains was combined with a highly

decorative treatment of the

several

parts by carving, moulding, and

arcading. The ceiling surfaces

between the

trusses

were handled decoratively, and the

oaken open-timber ceilings of many of

the

English

churches and civic or academic

halls (Christ Church Hall,

Oxford;

Westminster

Hall, London) are such noble

and beautiful works as quite to justify

the

substitution

of wooden for vaulted ceilings

(Fig. 138). The hammer-beam

truss

was

in

its way as highly scientific, and

æsthetically as satisfactory, as any

feature of

French

Gothic stone construction. Without the

use of tie-rods to keep the

rafters from

spreading,

it brought the strain of the roof upon

internal brackets low down on the

wall,

and produced a beautiful effect by the

repetition of its graceful

curves in each

truss.

CHAPELS

AND HALLS. Many of

these rival the cathedrals in beauty and

dignity of

design.

The royal chapels at Windsor and

Westminster have already

been mentioned,

as

well as King's College Chapel at

Cambridge, and Christ Church Hall at

Oxford. To

these

college halls should be

added the chapel of Merton College at

Oxford, and the

beautiful

chapel of St. Stephen at

Westminster, most unfortunately

demolished when

the

present Parliament House was

erected. The Lady-chapels of Gloucester

and Ely,

though

connected with the cathedrals, are

really independent designs of

late date,

and

remarkable for the richness of their

decoration, their great windows,

and

elaborate

ribbed vaulting. Some of the

halls in mediæval castles and

manor-houses

are

also worthy of note, especially for their

timber ceilings.

MINOR

MONUMENTS. The

student of Gothic architecture

should also give

attention

to the choir-screens, tombs, and

chantries which embellish many of

the

abbeys

and cathedrals. The rood-screen at York is a

notable example of the first;

the

tomb

of De Gray in the same cathedral, and

tombs and chantries in

Canterbury,

Winchester,

Westminster Abbey, Ely, St.

Alban's Abbey, and other

churches are

deservedly

admired. In these the English

love for ornament, for minute carving,

and

for

the contrast of white and colored marble,

found unrestrained expression. To

these

should

be added the market-crosses of Salisbury

and Winchester, and Queen

Eleanor's

Cross at Waltham.

DOMESTIC

ARCHITECTURE. The

mediæval castles of Great

Britain belong to the

domain

of military engineering rather than of the

history of art, though

occasionally

presenting

to view details of considerable

architectural beauty. The growth of

peace

and

civic order is marked by the

erection of manor-houses, the residences

of wealthy

landowners.

Some of these houses are of

imposing size, and show the application

to

domestic

requirements, of the late Gothic

style which prevailed in the period

to

which

most of them belong. The windows are

square or Tudor-arched, with

stone

mullions

and transoms of the Perpendicular style,

and the walls terminate in

merlons

or

crenelated parapets, recalling the

earlier military structures. The palace

of the

bishop

or archbishop, adjoining the cathedral,

and the residences of the dean,

canons,

and clergy, together with the libraries,

schools, and gates of the

cathedral

enclosure,

illustrate other phases of

secular Gothic work. Few of

these structures are

of

striking architectural merit, but they

possess a picturesque charm which is

very

attractive.

Not

many stone houses of the smaller

class remain from the Gothic

period in

England.

But there is hardly an old town that does not

retain many of the half-

timbered

dwellings of the fifteenth or even

fourteenth century, some of them

in

excellent

preservation. They are for the most part

wider and lower than the

French

houses

of the same class, but are built on the

same principle, and, like them,

the

woodwork

is more or less richly

carved.

MONUMENTS:

(A. = abbey church; C. =

cathedral; r. = ruined; trans. =

transept; each

monument

is given under the date of

the earliest extant Gothic

work upon it, with

additions

of later periods in

parentheses.)

EARLY ENGLISH: Kirkstall A., 115282,

first pointed arches;

Canterbury C., choir,

1175

84

(nave, 13781411; central tower,

1500); Lincoln C., choir,

trans., 11921200

(vault,

1250; nave and E. end, 126080);

Lichfield C., 120050 (W.

front, 1275;

presbytery,

1325); Worcester C., choir,

120318, nave partly Norman

(W. end, 1375

95);

Chichester C., 120444 (spire

rebuilt 17th century); Fountains

A., 120546;

Salisbury

C., 122058 (cloister, chapter-h.,

126384; spire, 1331); Elgin

C., 122444;

Wells

C., 11751206 (W. front 1225,

choir later, chapter-h.,

1292); Rochester C.,

122539

(nave Norman); York C., S.

trans., 1225; N. trans., 1260 (nave,

chapter-h.,

12911345;

W. window, 1338; central tower, 13891407; E.

window, 1407);

Southwell

Minster, 123394 (nave Norman);

Ripon C., 123394 (central

tower, 1459);

Ely

C., choir, 122954

(nave Norman; octagon

and presbytery,

132362);

Peterborough

C., W. front, 1237 (nave

Norman; retro-choir, late 14th

century);

Netley

A., 1239 (r.); Durham C.,

"Nine Altars" and E. end

choir, 123590 (nave,

choir,

Norman;

W. window, 1341; central tower finished,

1480); Glasgow C., (with

remarkable

Early

English crypt), 124277; Gloucester

C., nave vaulted, 123942

(nave mainly

Norman;

choir, 133751; cloisters, 13751412; W.

end, 142037; central

tower,

145057);

Westminster A., 124569; St.

Mary's A., York, 127292

(r.).

DECORATED:

Merton College Chapel,

Oxford, 12741300; Hereford C., N.

trans.,

chapter-h.,

cloisters, vaulting, 127592 (nave,

choir, Norman); Exeter C.,

choir, trans.,

127991;

nave, 133150 (E. end

remodelled, 1390); Lichfield

C., Lady-chapel, 1310;

Ely

C., Lady-chapel, 132149; Melrose

A., 132799 (nave, 1500; r.);

St. Stephen's

Chapel,

Westminster, 134964 (demolished);

Edington church, 135261; Carlisle

C.,

E.

end and upper parts,

135295 (nave in part and S.

trans. Norman; tower

finished,

1419);

Winchester C., W. end

remodelled, 136066 (nave and

aisles, 13941410;

trans.,

partly Norman); York C.,

Lady-chapel, 136272; churches of

Patrington and Hull,

late

14th century.

PERPENDICULAR: Holy Cross Church,

Canterbury, 1380; St. Mary's,

Warwick, 138191;

Manchester

C., 1422; St. Mary's, Bury

St. Edmunds, 142433; Beauchamp

Chapel,

Warwick,

1439; King's College Chapel,

Cambridge, 1440; vaults, 150815; St.

Mary's

Redcliffe,

Bristol, 1442; Roslyn Chapel,

Edinburgh, 144690; Gloucester C.,

Lady-

chapel,

145798; St. Mary's,

Stratford-on-Avon, 146591; Norwich

C., upper part

and

E.

end of choir, 147299 (the

rest mainly Norman); St.

George's Chapel,

Windsor,

14811508;

choir vaulted, 150720; Bath

A., 150039; Chapel of Henry

VII.,

Westminster,

150320.

ACADEMIC AND SECULAR BUILDINGS: Winchester Castle Hall,

122235; Merton College

Chapel,

Oxford, 12741300; Library Merton

College, 135478; Norborough

Hall,

1356;

Windsor Castle, upper ward,

135973; Winchester College, 138793;

Wardour

Castle,

1392; Westminster Hall, rebuilt,

139799; St. Mary's Hall,

Coventry, 140114;

Warkworth

Castle, 1440; St. John's

College, All Soul's College,

Oxford, 1437; Eton

College,

14411522; Divinity Schools, Oxford,

144554; Magdalen College,

Oxford,

147580,

tower, 1500; Christ Church

Hall, Oxford, 1529.

Table of Contents:

- PRIMITIVE AND PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE:EARLY BEGINNINGS

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, THE MIDDLE EMPIRE

- EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:TEMPLES, CAPITALS

- CHALDÆAN AND ASSYRIAN ARCHITECTURE:ORNAMENT, MONUMENTS

- PERSIAN, LYCIAN AND JEWISH ARCHITECTURE:Jehovah

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE:GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS, THE DORIC

- GREEK ARCHITECTURE—Continued:ARCHAIC PERIOD, THE TRANSITION

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE:LAND AND PEOPLE, GREEK INFLUENCE

- ROMAN ARCHITECTURE—Continued:IMPERIAL ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY, RAVENNA

- BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE:DOMES, DECORATION, CARVED DETAILS

- SASSANIAN AND MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE:ARABIC ARCHITECTURE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE:LOMBARD STYLE, FLORENCE

- EARLY MEDIÆVAL ARCHITECTURE.—Continued:EARLY CHURCHES, GREAT BRITAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE:STRUCTURAL PRINCIPLES, RIBBED VAULTING

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN:GENERAL CHARACTER

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, THE NETHERLANDS, AND SPAIN

- GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:CLIMATE AND TRADITION, EARLY BUILDINGS.

- EARLY RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY:THE CLASSIC REVIVAL, PERIODS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN ITALY—Continued:BRAMANTE’S WORKS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN FRANCE:THE TRANSITION, CHURCHES

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GREAT BRITAIN AND THE NETHERLANDS

- RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN GERMANY, SPAIN, AND PORTUGAL

- THE CLASSIC REVIVALS IN EUROPE:THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

- RECENT ARCHITECTURE IN EUROPE:MODERN CONDITIONS, FRANCE

- ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES:GENERAL REMARKS, DWELLINGS

- ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE:INTRODUCTORY NOTE, CHINESE ARCHITECTURE

- APPENDIX.