|

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

LESSON

09

DIGESTIVE

AND RENAL SYSTEMS

THE

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Whether

we eat an apple, drink some

milk, or swallow a pill, our

bodies respond in the same

general Way.

The

digestive system breaks down

what we have ingested, converts

much of it to chemicals the body

can

use,

and excretes the rest. The

chemicals the body uses are

absorbed into the bloodstream,

which transports

them

to all of our body cells.

Chemical nutrients in the foods we eat

provide energy to fuel our

activity,

body

growth, and repair.

Food's

Journey through Digestive

Organs

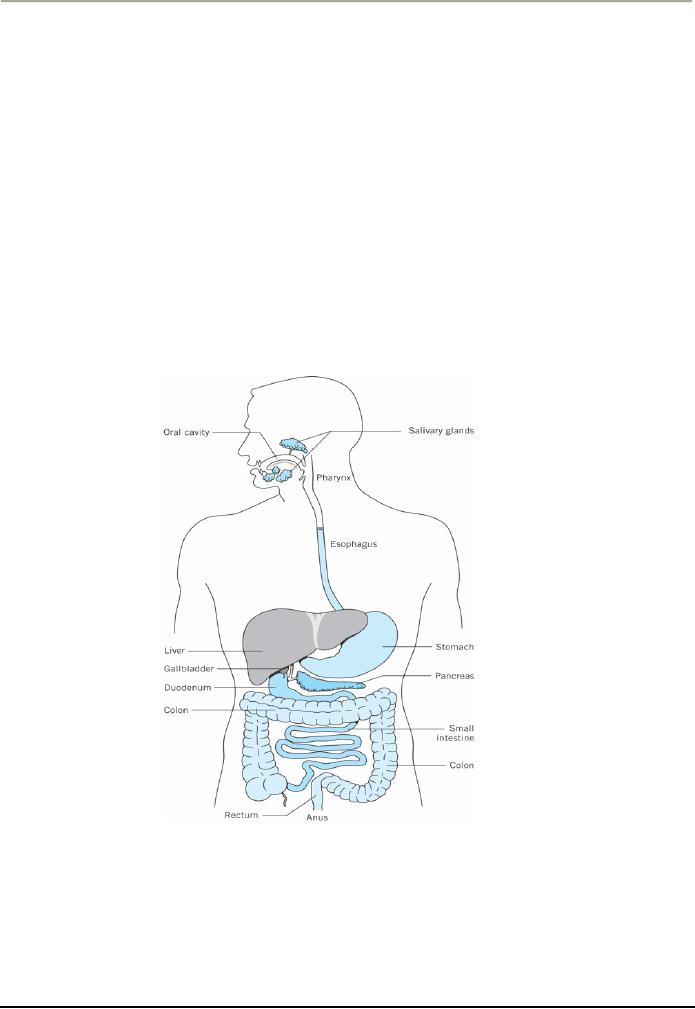

Think

of the digestive system as a long

hose-- about 20 feet long--with

stations along the way.

The

journey

of food through this hose

begins in the mouth and ends

at the rectum. These digestive

organs and

the

major organs in between are

shown in the diagram.

Digesting

Food

How

does this system break down

food? One way is mechanical: for

example, we grind food up

when we

chew

it. Another way is chemical:

by the action of enzymes, substances that

act as catalysts in speeding

up

chemical

reactions in cells. How do

enzymes work? You can see the effect of

an enzyme by doing the

following

experiment. Place a bit of liver in

some hydrogen peroxide and watch what

happens:

40

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

An

enzyme in liver called

catalase

causes

the peroxide to decompose, frothing as

oxygen is given off as a

gas.

This is the same reaction you see

when you use peroxide to disinfect a

wound.

In

most cases, the names for

enzymes end in the letters

-ase, and

the remainder of each name

reflects the

substance

on which it acts. The

following list gives some

examples:

·

Carbohydrase acts on

carbohydrates.

·

Lactase acts on lactose

(milk).

·

Phosphatase acts on phosphate

compounds.

·

Sucrase acts on sucrose

(sugar).

As

food is broken down into

smaller and smaller units in the

digestive tract, water

molecules become

attached

to these units. When food is in the

mouth, there is more

digestive action going on than

just

chewing.

Saliva moistens food and

contains an enzyme that

starts the process of breaking down

starches.

The

salivary glands release

saliva in response to commands

from the brainstem, which

responds primarily to

sensory

information from taste buds.

Simply seeing, smelling, or

even thinking about food can

produce

neural

impulses that cause the

mouth to water.

The

journey of food advances to the

esophagus, a tube that is normally

flattened when food is not

passing

through

it. The esophagus pushes the

food down to the stomach by wavelike

muscle contractions called

peristalsis. By the time

food enters the esophagus, the

stomach has already begun

digestive activities by

releasing

small amounts of gastric

juice even before food

reaches it. Tasting,

smelling, seeing, or

thinking

about

food can initiate this

process. Once food reaches

the stomach, this organ amasses

large amounts of

gastric

juices, including hydrochloric

acid and pepsin, an enzyme

that breaks down proteins.

The stomach

also

produces a sticky mucus

substance to protect its

lining from the highly

acidic gastric

juices.

The

muscular stomach walls

produce a churning motion--that we

are generally not aware

of--which mixes

the

food particles with the

gastric juices. This mixing

continues for 3 or 4 hours,

producing a semi-

liquid

mixture.

Peristalsis in the stomach then

moves this mixture on, a

little at a time, to the initial section

of the

small

intestine called the duodenum.

Important

digestive processes occur in the

small intestine. First, the highly acidic

food mixture becomes

chemically

alkaline as a result of substances added

from the pancreas, gallbladder, and wall

of the small

intestine.

This is important because the

linings of the small intestine and

remainder of the digestive tract

are

not

protected from high acidity, as the

stomach is. Second, enzymes

secreted by the pancreas into

the

duodenum

break down carbohydrates, proteins,

and fats further. Third,

absorption increases. Because

the

stomach

lining can absorb only a

few substances, such as alcohol

and aspirin, most materials

we ingest are

absorbed

into the bloodstream through the

lining of the small intestine. If alcohol is

consumed along with

fatty

foods, very little alcohol is absorbed

until it reaches the small intestine. By

the time food is ready to be

absorbed

through the intestine wall, nutrients have

been broken down into

molecules--carbohydrates are

broken

down into simple sugars,

fats into glycerol and fatty

acids, and proteins into amino

acids.

How

does Absorption Occur?

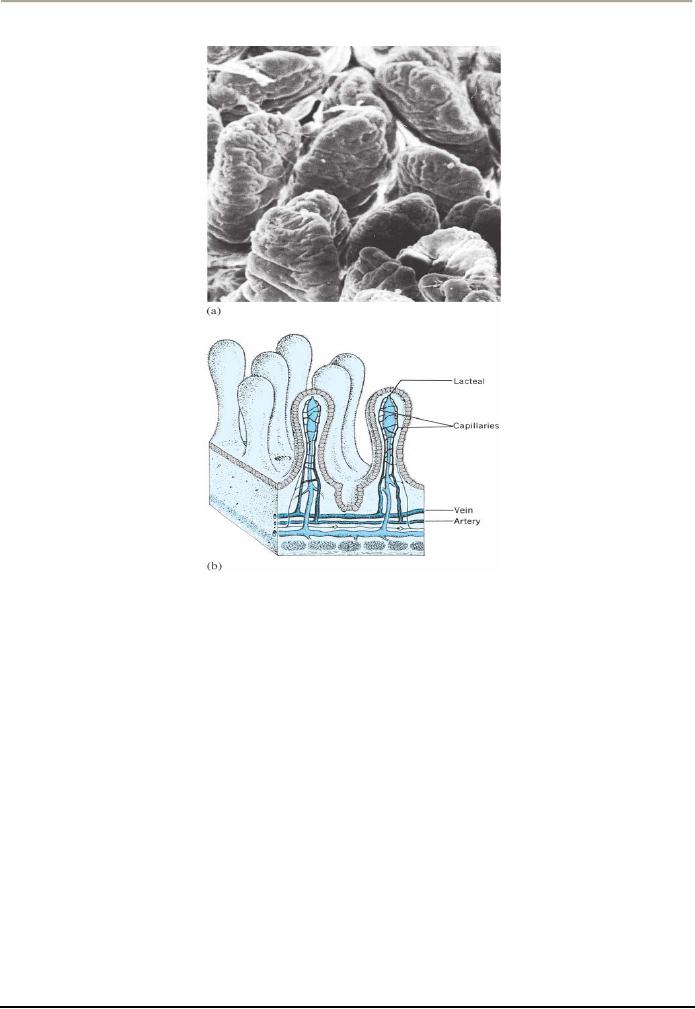

The

inside of the small intestine is made of

a membrane that will allow

molecules to pass through.

To

increase

the absorbing surface, the intestine wall

has many folds that contain

projections, as pictured in the

diagram.

41

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

Each

of the many thousands of projections

contains a network of structures

that will accept the

molecules

and

transport them away to other parts of the

body. These structures include

tiny blood vessels

called

capillaries

and a

tube called a lacteal.

Capillaries

absorb amino acids, simple

sugars, and water; they also

absorb some fatty acids,

vitamins, and

minerals.

Lacteals accept glycerol and the

remaining fatty acids and

vitamins.

The

remaining food material continues

its journey to the large intestine,

most of which is called the

colon.

Absorption,

mainly of water, continues in the first

half of the colon, and the remaining

material is

transported

on. Bacterial action converts the

material into feces, which

eventually reach the rectum,

where

they

are stored until defecation

occurs.

Disorders

of the Digestive

System

Judging

from the many media

advertisements for stomach

and "irregularity" remedies, it

seems that people

have

a good deal of trouble with

their digestive processes. We

will consider a few digestive

problems. One

disorder

of the digestive system is peptic

ulcers.

42

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

Peptic

Ulcers are

open sores in the lining of

the

stomach or intestine, usually in

the

duodenum.

These sores appear to result

from

excess

gastric juices chronically eroding

the

lining

when there is little or no

food in the

stomach,

but bacterial infection can

play a

role,

too. Abdominal pain is the

chief

symptom

of the disorder. Although the

victims

of ulcers are mostly adults,

the

disorder

also occurs in children,

particularly

boys.

People who experience high

levels of

stress

seem to be more susceptible to

ulcers

than

people who do not.

Hepatitis

is a

class of several viral

diseases in

which

the liver becomes inflamed

and unable

to

function well. The first

symptoms often are

like

those of flu. But the

symptoms persist,

and

jaundice, a yellowing of the skin,

generally

follows.

Hepatitis A appears to be

transmitted

through

contaminated food, water, and

utensils. Hepatitis B and C infections

occur through sexual

contact,

transfusion

of infected blood, and sharing of

contaminated needles by drug addicts,

but the modes of

transmission

may be broader. Some forms of hepatitis

can lead to permanent liver

damage.

Cirrhosis

is another

disease of the liver. In this disease,

liver cells die off and

are replaced by

nonfunctional

fibrous

scar tissue. The scar

tissue is permanent, and when it

becomes extensive, the livers normal

functions

are

greatly impaired. As we will see later, the

liver is not only important

in the digestive process; it

also

cleanses

and regulates the composition of the

blood. Cirrhosis can result

from several causes,

including

hepatitis

infection and, particularly, alcohol

abuse (AMA, 1989).

Cancer

may

occur in any part of the

digestive tract, especially in the

colon and rectum. People

over 40 years

of

age have a higher prevalence

for cancers of the digestive tract than

do younger individuals. Early

detection

for many of these cancers is

possible and greatly improves the

person's chances of

recovery.

THE

RENAL SYSTEM

Overview

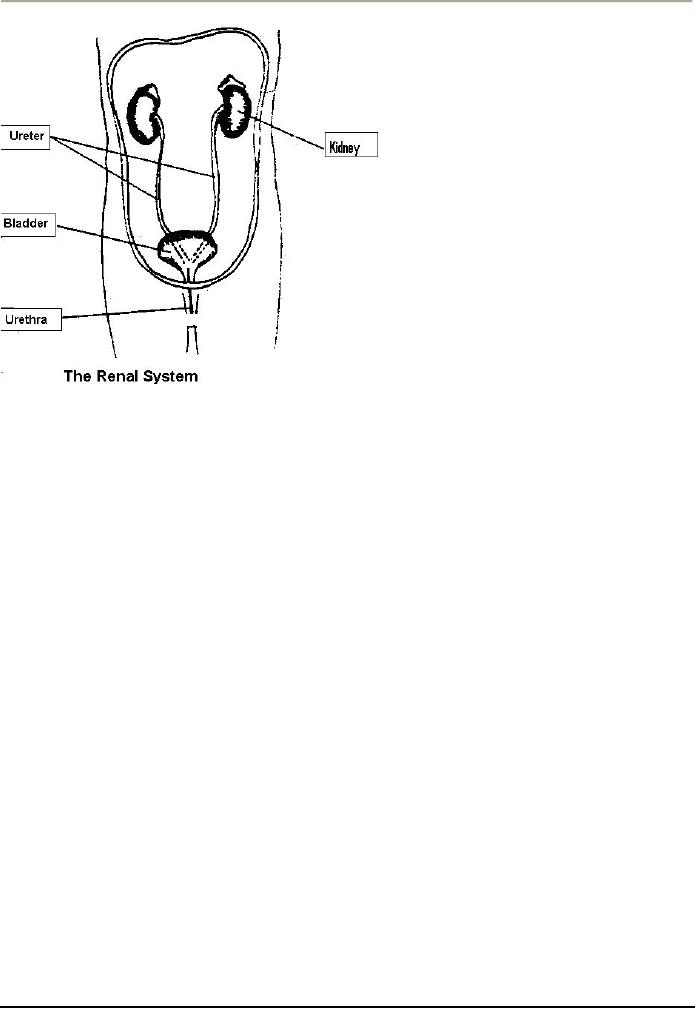

The

renal system--consisting of the kidneys,

ureters, urinary bladder, and

urethra--is also critically

important

in metabolism. The kidneys

are chiefly responsible for

the regulation of the bodily fluids;

their

principal

function is to produce urine. The ureters

contain smooth muscle tissue that

contracts, causing

peristaltic

waves to move urine to the bladder, a

muscular bag that acts as a

reservoir for urine. The

urethra

then

conducts urine from the bladder

out of the body.

Urine

contains surplus water,

surplus electrolytes; waste products

from the metabolism of food,

and surplus

acids

or alkalis. By carrying these products

out of the body, it main- tabs

water balance, electrolyte

balance,

and

blood pH. Of the electrolytes,

sodium and potassium are the

most important because they

are involved

in

the normal chemical reactions of the

body, muscular contractions,

and the conduction of nerve

impulses.

Thus,

an important function of the kidneys is

to maintain an adequate balance of sodium

and potassium

ions.

In the case of certain diseases, the

urine will also contain abnormal

amounts of some

constituents;

therefore,

urinalysis offers important diagnostic

clues to many disorders. For

example, an excess of

glucose

43

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

may

indicate diabetes, an excess of red

blood cells may indicate a

kidney disorder, and so on.

This is one of

the

reasons why a medical

checkup often includes a

urinalysis.

As

noted, one of the chief functions of the

kidneys is to control the water

balance in the body. For

example,

on

a hot day when a person has

been active and has

perspired profusely, relatively little

urine will be

produced

so that the body may retain

more water. This is because

much water has already

been lost through

the

skin. On the other hand, on a cold

day when a person is relatively inactive

and a good deal of liquid

has

been

consumed, urine output will

be higher so as to prevent

over-hydration.

To

summarize, then, the urinary system

regulates bodily fluids by

removing surplus water,

surplus

electrolytes,

and the waste products

generated by the metabolism of

food.

Disorders

of the Renal

System

The

renal system is vulnerable to a number of

disorders. Among the most

common are urinary

tract

infections,

to which women are

especially vulnerable and which

can result in considerable pain,

especially

upon

urination. If untreated, they can

lead to more serious

infection.

AGN

(Acute Glomerular Nephritis) is a

disease that results from an

antigen-antibody reaction in which

the

inner tissues of the kidneys

become markedly inflamed. These

inflammatory reactions can

cause total or

partial

blockage in the kidneys. In severe

cases, total renal shutdown

occurs. Acute glomerular nephritis

is

usually

caused by a kind of streptococcus

infection.

Another

common cause of acute renal shutdown is

tubular

necrosis,

which involves destruction of the

epithelial

cells in the tubules of the kidneys.

Poisons that destroy the

tubular epithelial cells or

severe

circulatory

shock are most common causes

of tubular necrosis.

Kidney

Failure is a

severe disorder because the inability to

produce an adequate amount of urine

will cause

the

waste products of metabolism as well as

surplus inorganic salts and

water to be retained in the body.

An

artificial

kidney, a kidney transplant, or kidney

dialysis may be required in order to

rid the body of its

wastes.

Although

these technologies can

cleanse the blood to remove the

excess salts, water, and

metabolites, they

are

highly stressful medical

procedures. Kidney transplants

carry many health risks, and

kidney dialysis can

be

extremely uncomfortable for patients.

Consequently, health psychologists have

been involved in

addressing

the problems of the kidney

patient.

44

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Health and Wellness Defined

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Early Cultures, The Middle Ages

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Psychosomatic Medicine

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:The Background to Biomedical Model

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:THE LIFE-SPAN PERSPECTIVE

- HEALTH RELATED CAREERS:Nurses and Physician Assistants, Physical Therapists

- THE FUNCTION OF NERVOUS SYSTEM:Prologue, The Central Nervous System

- THE FUNCTION OF NERVOUS SYSTEM AND ENDOCRINE GLANDS:Other Glands

- DIGESTIVE AND RENAL SYSTEMS:THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM, Digesting Food

- THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM:The Heart and Blood Vessels, Blood Pressure

- BLOOD COMPOSITION:Formed Elements, Plasma, THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

- SOLDIERS OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM:Less-Than-Optimal Defenses

- THE PHENOMENON OF STRESS:Experiencing Stress in our Lives, Primary Appraisal

- FACTORS THAT LEAD TO STRESSFUL APPRAISALS:Dimensions of Stress

- PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF STRESS:Cognition and Stress, Emotions and Stress

- SOURCES OF STRESS:Sources in the Family, An Addition to the Family

- MEASURING STRESS:Environmental Stress, Physiological Arousal

- PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS THAT CAN MODIFY THE IMPACT OF STRESS ON HEALTH

- HOW STRESS AFFECTS HEALTH:Stress, Behavior and Illness, Psychoneuroimmunology

- COPING WITH STRESS:Prologue, Functions of Coping, Distancing

- REDUCING THE POTENTIAL FOR STRESS:Enhancing Social Support

- STRESS MANAGEMENT:Medication, Behavioral and Cognitive Methods

- THE PHENOMENON OF PAIN ITS NATURE AND TYPES:Perceiving Pain

- THE PHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN PERCEPTION:Phantom Limb Pain, Learning and Pain

- ASSESSING PAIN:Self-Report Methods, Behavioral Assessment Approaches

- DEALING WITH PAIN:Acute Clinical Pain, Chronic Clinical Pain

- ADJUSTING TO CHRONIC ILLNESSES:Shock, Encounter, Retreat

- THE COPING PROCESS IN PATIENTS OF CHRONIC ILLNESS:Asthma

- IMPACT OF DIFFERENT CHRONIC CONDITIONS:Psychosocial Factors in Epilepsy