|

DECORATIVE DRAWING |

| << ARCHITECTURAL DRAWING |

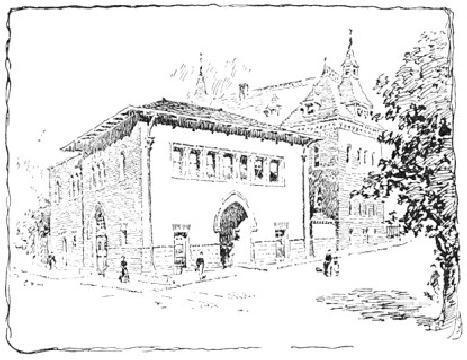

FIG.

60

C. D.

M.

Another

scheme for the treatment of

this same subject is

illustrated by

Fig.

60. Here, by the

introduction of the tree at the

right of the picture,

a

triangular

composition is adopted. Observe that

the sidewalk and roof

lines

at the left side of the

building radiate to the bottom and

top of the

tree

respectively. The shadow of

the tree helps to form the

bottom line of

the

triangle. In this case the

foreground figure is omitted, as it

would

have

made the triangularity too

obvious. In the color-scheme

the tree is

made

the principal dark, and this

dark is repeated in the

cornice shadow,

windows

and figures as before. The

gray tone of the old

building

qualifies

the blackness of the tree,

which would otherwise have

made too

strong

a contrast at the edge of

the picture, and so detracted from

the

interest

of the main building.

CHAPTER

VII

DECORATIVE

DRAWING

In

all modern decorative

illustration, and, indeed, in

all departments of

decorative

design, the influences of two

very different and distinct

points

of

view are noticeable; the one

demanding a realistic, the

other a purely

conventional

art. The logic of the

first is, that all good

pictorial art is

essentially

decorative; that of the second,

that the decorative subject

must

be

designed in organic relation to

the space which it is to

occupy, and be

so

treated that the design will primarily

fulfil a purely

ornamental

function.

That is to say, whatever of

dramatic or literary interest

the

decorative

design may possess must be,

as it were, woven into it,

so that

the

general effect shall please

as instantly, as directly, and as

independently

of the meaning, as the

pattern of an Oriental rug.

The

former,

it will be seen, is an imitative, the

latter an inventive art. In

the

one,

the elements of the subject

are rendered with all possible

naturalism;

while,

in the other, effects of atmosphere and

the accidental play of

light

and

shade are sacrificed to a

conventional rendering, by which

the design

is

kept flat upon the

paper or wall. One

represents the point of view

of

the

painter and the pictorial

illustrator; the other that

of the designer and

the

architect. The second, or conventional

idea, has now come to be

widely

accepted as a true basic

principle in decorative

art.

The

idea is not by any means

novel; it has always been

the fundamental The

New

principle

of Japanese art; but its

genesis was not in Japan.

The immediate Decorative

inspiration

of the new Decorative

school, as far as it is concerned

with School

the

decoration of books, at least, was found

in the art of Dürer,

Holbein,

and

the German engravers of the

sixteenth century,--interest in

which

period

has been lately so

stimulated by the Arts and

Crafts movement in

England.

This movement, which may

fairly be regarded as one of

the

most

powerful influences in latter-day

art, was begun with

the aim of

restoring

those healthy conditions which

obtained before the artist

and

the

craftsman came to be two

distinct and very much

extranged workers.

The

activities of the movement

were at first more directly

concerned

with

the art of good book-making,

which fructified in the

famous

Kelmscott

Press (an institution which,

while necessarily

undemocratic,

has

exerted a tremendous influence on

modern printing), and to-day

there

is

scarcely any sphere of

industrial art which has

not been influenced

by

the

Arts and Crafts

impetus.

This

modern decorative renaissance

has a root in sound art

principles, Criticisms

of

which

promises for it a vigorous vitality; and

perhaps the only serious

the

School

criticism

which has been directed

against it is, that it encourages

archaic

crudities

of technique which ignore

the high development of

the

reproductive

processes of the present day;

and, moreover, that

its

sympathies

tend towards mediæval life

and feeling. While such

a

criticism

might reasonably be suggested by

the work of some of

its

individual

adherents, it does not touch in

the least the essential

principles

of

the school. Art cannot be

said to scout modernity

because it refuses to

adjust

itself to the every caprice of Science.

The architect rather

despises

the

mechanically perfect brick

(very much to the surprise

of the

manufacturer);

and though the camera can

record more than the

pencil or

the

brush, yet the artist is

not trying to see more

than he ever did

before.

There

are, too, many decorative

illustrators who, while very

distinctly

confessing

their indebtedness to old examples;

are yet perfectly

eclectic

and

individual, both in the

choice and development of motive.

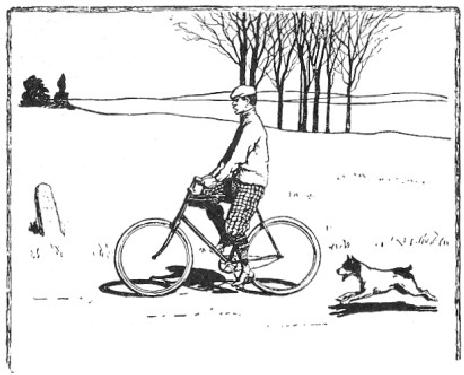

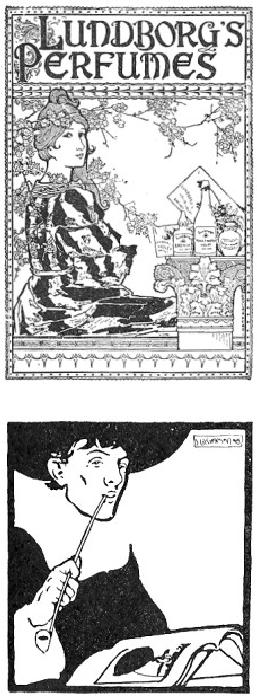

Take, for

example,

the very modern subject of

the cyclist by Mr. A. B. Frost,

Fig.

61.

There are no archaisms in it whatever.

The drawing is as

naturalistic

and

just as careful as if it were

designed for a picture. The

shadows, too,

are

cast, giving an effect of

strong outdoor light; but

the treatment, broad

and

beautifully simple so as to be

reconcilable with the

lettering which

accompanied

it, is well within

conventional lines. That the

character of

the

technical treatment is such as to place

no tax on the

mechanical

inventiveness

of the processman is not

inexcusable archæology.

FIG.

61

A.

B. FROST

A

valuable attribute of this

conventional art is, that it

puts no bounds to

the

fancy of the designer. It is a

figurative language in which he

may get

away

from commonplace statement.

What has always seemed to me

a

very

logical employment of convention

appears in the Punch

cartoons

of

Sir

John Tenniel and Mr. Lindley

Sambourne. Even in those

cartoons

which

are devoid of physical

caricature (and they are

generally free from

this),

we see at a glance that it is

the political and not the

personal

relations

of the personæ that are

represented; whereas in the

naturalistic

cartoons

of Puck,

for example, one cannot resist

the feeling that

personalities

are being roughly

handled.

A

chief principle in all

decorative design and treatment is

that of Relation

Relation.

If the space to be ornamented be a

book-page the design and

treatment

must be such as to harmonize

with the printing. The

type must

be

considered as an element in the design,

and, as the effect of a page

of

type

is broad and uniformly flat,

the ornament must be made to

count as

broad

and flat likewise. The same

principle holds equally in

mural

decoration.

There the design ought to be

subordinate to the general

effect

of

the architecture. The wall

is not to be considered merely as

a

convenient

place on which to plaster a picture,

its structural purpose

must

be regarded, and this cannot be expressed

if the design or treatment

be

purely pictorial--if vague perspective

distances and strong

foreground

accents be used without

symmetry or order, except

that order

which

governs itself alone. In

other words, the decoration

must be

organic.

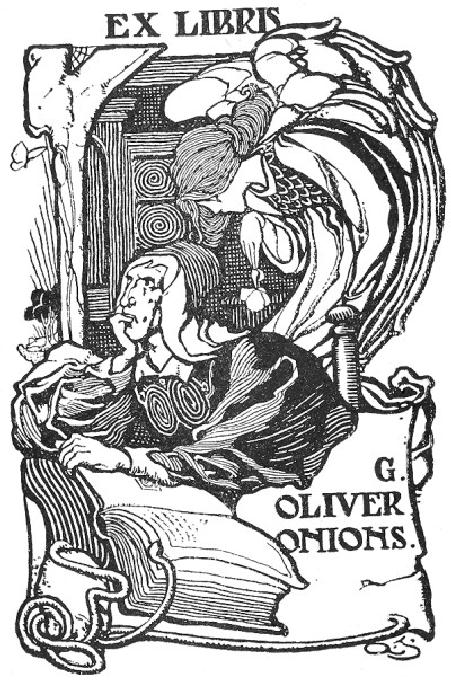

FIG.

62

ALFRED

G. JONES

Decorative

illustrations may be broadly

classified under three heads

as Classes

of

follows:

First, those wherein the

composition and the treatment

are both Decorative

conventional,

as, for example, in the

ex-libris by Mr. A. G. Jones, Fig.

Design

62.

Second, where the composition is

naturalistic, and the treatment

only

is

conventional, as in Mr. Frost's design.

Third, where the composition

is

decorative

but not conventional, and

the treatment is semi-natural, as

in

the

drawing by Mr. Walter Appleton

Clark, Fig. 63. (The

latter subject is

of

such a character as to lend itself

without convention to a

decorative

effect;

and, although the figure is

modeled as in a pictorial

illustration,

the

organic lines are so emphasized

throughout as to preserve the

decorative

character, and the whole

keeps its place on the page.)

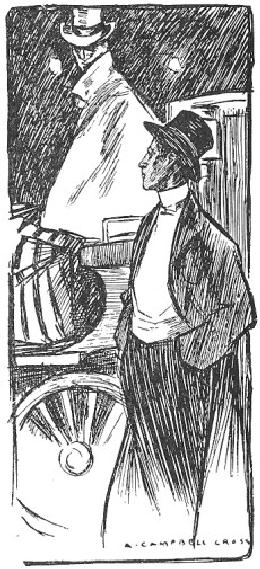

Under

this

third head would be included

those subjects of a pictorial

nature

whose

composition and values are

such as to make them reconcilable

to

a

decorative use by means of borders or

very defined edges, as in

the

illustration

by Mr. A. Campbell Cross, Fig.

64.

FIG.

63

W.

APPLETON CLARK

FIG.

64

A.

CAMPBELL CROSS

Another

essential characteristic of decorative

drawing is the The

emphasized

Outline. This may be heavy

or delicate, according to the

Decorative

nature

of the subject or individual

taste. The designs by Mr. W.

Outline

Nicholson

and Mr. Selwyn Image, for

instance, are drawn with a

fatness

of

outline not to be obtained

with anything but a brush;

while the

outlines

of M. Boutet de Monvel, marked as

they are, are evidently

the

work

of a more than usually fine

pen. In each case, however,

everything

is

in keeping with the scale of

the outline adopted, so that

this always

retains

its proper emphasis. The

decorative outline should

never be

broken,

but should be kept firm,

positive, and uniform. It may be

heavy,

and

yet be rich and feeling, as

may be seen in the Mucha

design, Fig.65.

Generally

speaking, the line ought not

to be made with a nervous

stroke,

but

rather with a slow, deliberate

drag. The natural wavering

of the hand

need

occasion no anxiety, and, indeed, it is

often more helpful to the

line

than

otherwise.

FIG.

65

MUCHA

Perhaps

there is no more difficult

thing to do well than to

model the

figure

while still preserving the

decorative outline. Several

examples of

the

skilful accomplishment of this

problem are illustrated

here. Observe,

for

instance, how in the quaint

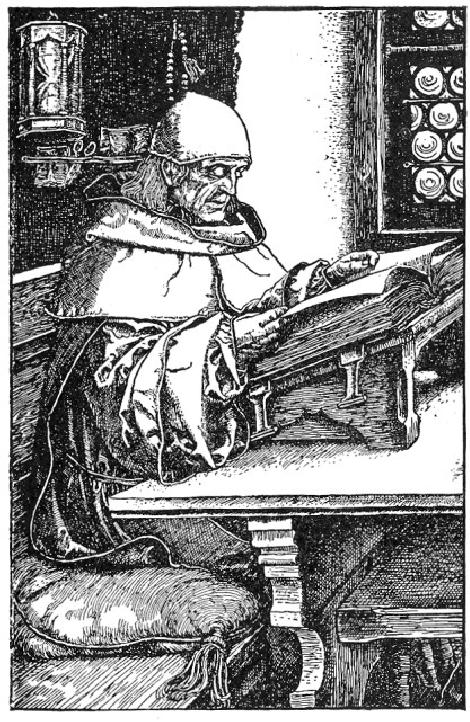

Dürer-like design by Mr. Howard

Pyle,

Fig.

66, the edges of the

drapery-folds are emphasized in the

shadow by

keeping

them white, and see how

wonderfully effective the

result is. The

same

device is also to be noticed in the

book-plate design by Mr. A. G.

Jones,

Fig. 62, as well as in the

more conventional treatment of

the black

figure

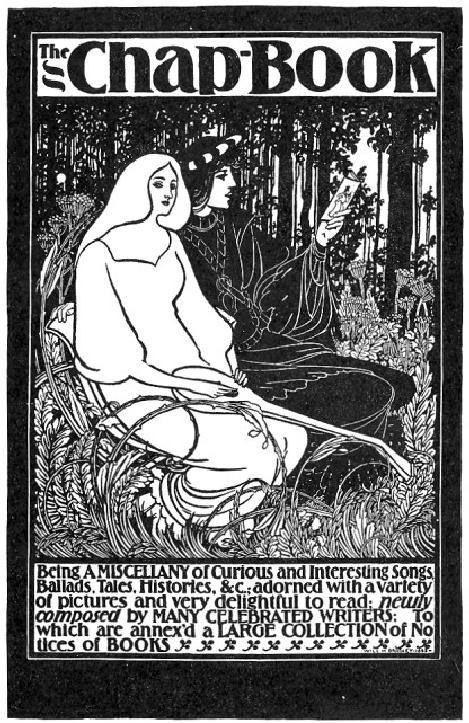

in the Bradley poster, Fig.

67.

FIG.

66

HOWARD

PYLE

FIG.

67

WILL

H. BRADLEY

In

the rendering of decorative

subjects, the Color should

be, as much as Color

possible,

designed. Whereas a poster, which is made

with a view to its

entire

effect being grasped at once,

may be rendered in flat masses

of

color,

the head- or tail-piece for a

decorative book-page should be

worked

out in more detail, and the

design should be finer and

more

varied

in color. The more the

color is attained by means of

pattern,

instead

of by mere irresponsible lines, the

more decorative is the

result.

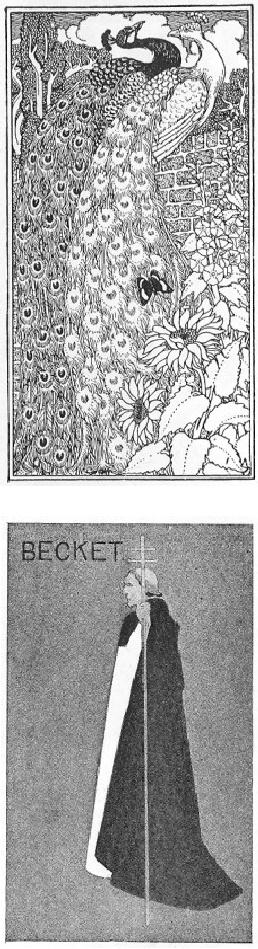

Observe

the color-making by pattern in

the book-plate by Mr. P. J.

Billinghurst,

Fig. 68. A great variety of

textures may be obtained

by

means

of varied patterns without affecting

the breadth of the

color-

scheme.

This may be noticed in the

design last mentioned, in which

the

textures

are extremely well rendered, as

well as in the poster design by

Mr.

Bradley for the Chap-Book,

just referred to.

FIG.

68

P.

J. BILLINGHURST

FIG.

69 "BEGGARSTAFF BROTHERS"

The

color-scheme ought to be simple

and broad. No set rules can

be

laid

down to govern its

disposition, which must

always have reference to

the

whole design. The importance

of employing such a broad and

simple

scheme

in decorative drawing needs no

better argument than

the

effective

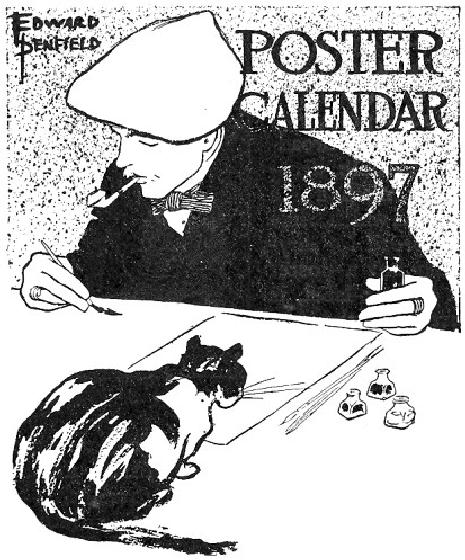

poster design by the "Beggarstaff

Brothers," Fig. 69, and

that

by

Mr. Penfield, Fig.70. Of course the

more conventional the design

the

less

regard need be paid to anything like a

logical disposition of color.

A

figure

may be set against a black

landscape with white trees

without fear

of

criticism from reasonable people,

provided it looks effective

there.

FIG.

70

EDWARD

PENFIELD

A

word or two, in conclusion,

concerning some of the

modern Modern

decorative

draughtsmen. Of those who work in

the sixteenth century

Decorative

manner,

Mr. Howard Pyle is unquestionably

the superior technician. His

Draughtsmen

line,

masterly in its sureness, is

rich and charged with feeling. Mr.

H.

Ospovat,

one of the younger group of

English decorators, has also a

charming

technique, rather freer than

that of Mr. Pyle, and yet

reminding

one

of it. Mr. Louis Rhead is another of

the same school, whose

designs

are

deserving of study. The

example of his work shown in

Fig. 71--

excellent

both in color and in drawing--is one of

his earlier designs. Mr.

J.

W. Simpson, in the book-plate,

Fig. 72, shows the

broadest possible

decorative

method; a method which,

while too broad for anything

but a

poster

or a book-label, is just what

the student should aim at

being able

to

attain.

FIG.

71

LOUIS

J. RHEAD

FIG.

72

J.

W. SIMPSON

Some

of those decorators whose work shows a

Japanese influence

have

a

most exquisite method. Of these,

that remarkable draughtsman,

M.

Boutet

de Monvel, easily takes the

first place. Those who have

had the

good

fortune to see his original

drawings will not easily

forget the

delicate

beauty of outline nor the

wonderfully tender coloring

which

distinguishes

them. Mr. Maxfield Parrish is

another masterly

decorator

who

is noted for his free

use of Japanese precedent as well as

for the

resourcefulness

of his technique. The

drawings of Mr. Henry

McCarter,

too,

executed as they are in pure

line, are especially

valuable to the

student

of the pen. In respect both

of the design and treatment

of

decorative

subjects, the work of the

late Aubrey Beardsley is

more

individual

than that of any other

modern draughtsman. That of

our own

clever

and eccentric Bradley, while

very clearly confessing

its

obligations,

has yet a distinctive character of

its own. The work of

the

two

latter draughts men,

however, is not to be recommended to

the

unsophisticated

beginner for imitation, for

it is likely to be more

harmful

than

otherwise. Nevertheless, by steering

clear of the grotesque

conventions

with which they treat

the human figure, by

carefully

avoiding

the intense blacks in which

a great deal of their work

abounds,

and

by generally maintaining a healthy

condition of mind, much is to

be

learned

from a study of their

peculiar methods.

End

of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Pen

Drawing, by Charles Maginnis

***

END OF THIS PROJECT

GUTENBERG EBOOK PEN DRAWING

***

*****

This file should be named 17502-h.htm or 17502-h.zip

*****

This

and all associated files of various formats will be found

in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/7/5/0/17502/

Produced

by Robert J. Hall

Updated

editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will

be renamed.

Creating

the works from public domain print editions means that

no

one

owns a United States copyright in these works, so the

Foundation

(and

you!) can copy and distribute it in the

United States without

permission

and without paying copyright royalties. Special

rules,

set

forth in the General Terms of Use part of

this license, apply to

copying

and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

to

protect

the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and

trademark. Project

Gutenberg

is a registered trademark, and may not be

used if you

charge

for the eBooks, unless you receive specific

permission. If you

do

not charge anything for copies of this eBook,

complying with the

rules

is very easy. You may use this

eBook for nearly any

purpose

such

as creation of derivative works, reports, performances

and

research.

They may be modified and printed

and given away--you may

do

practically

ANYTHING with public domain eBooks.

Redistribution is

subject

to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

***

START: FULL LICENSE

***

THE

FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG

LICENSE

PLEASE

READ THIS BEFORE YOU

DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To

protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the

free

distribution

of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or

any other work associated in any way with

the phrase "Project